The American Bullfrog (Aquarana catesbeiana), formerly classified as Lithobates catesbeianus, is one of the largest and most recognizable frogs in North America. Its powerful croak resembles the bellowing of a bull, giving it its common name. Native to the eastern United States and Canada, the American bullfrog (A. catesbeiana) is an aquatic species of economic importance and a globally distributed invasive organism with high environmental adaptability (Zhang et al., 2025).

The commercial exploitation of the American bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus) has existed since the late 19th century, primarily for the consumption of frog legs (Dodd & Jennings, 2021). This article explores in depth all aspects of the American Bullfrog (Aquarana catesbeiana), from its taxonomy and physical characteristics to its life cycle, diet, habitat, behavior, its complex role as both a native and invasive species, and its aquaculture. We will also discuss considerations for those interested in keeping the American bullfrog as a pet.

- 1 Taxonomy and Nomenclature

- 2 Physical Characteristics of the American Bullfrog

- 3 Distribution and Habitat of the American Bullfrog

- 4 Reproduction and Life Cycle of the American Bullfrog

- 5 Diet of the American Bullfrog

- 6 Ecology and Behavior

- 7 Conservation Status and Invasive Impact

- 8 Care of the American Bullfrog

- 9 Aquaculture of the American Bullfrog

- 10 Diseases

- 11 Conclusion

- 12 References

- 13 Entradas relacionadas:

Taxonomy and Nomenclature

The classification of the American bullfrog has been a subject of debate among taxonomists. Traditionally placed in the genus Rana, it was later moved to the genus Lithobates. More recently, some studies suggest that it may belong to a distinct genus, Aquarana, resulting in the name Aquarana catesbeiana.

The specific epithet catesbeianus honors the English naturalist Mark Catesby, who first described it. For the purposes of this article and following predominant usage, we will primarily refer to it as Aquarana catesbeiana, recognizing Lithobates catesbeianus as a taxonomic alternative. The common name, American bullfrog (bullfrog American), is universally recognized.

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Amphibia

Order: Anura

Family: Ranidae

Genus: Aquarana

Species: Aquarana catesbeiana (Previously: Lithobates catesbeianus, Rana catesbeiana)

Common name in Spanish: rana toro americana, rana mugidora, rana toro

Common names in English: American Bullfrog, bullfrog American, common bullfrog, bullfrog, North American bullfrog.

Zhang et al. (2025) produced a high-quality chromosome-level genome assembly for the American bullfrog (A. catesbeiana); the assembly comprises 13 chromosomes with a total length of 6.32 Gb and an N50 scaffold length of 691.8 Mb.

Physical Characteristics of the American Bullfrog

Size and Weight of Lithobates catesbeianus

One of the most notable characteristics of the American bullfrog is its impressive size. American bullfrogs are the largest frogs in North America. They typically reach a snout-vent length (SVL) of 9 to 15 cm (3.5 to 6 inches), but exceptionally large individuals can exceed 20 cm (8 inches).

The largest recorded American bullfrog measured 20.3 cm (8 inches) in length, and considering their extended legs, they can appear even larger.

The weight of the American bullfrog varies significantly with size and condition, but large adults can weigh more than 0.5 kg (1.1 lbs), with records of specimens exceeding one kilogram. There is a direct correlation between size and age, as well as the availability of resources in its habitat. The largest American bullfrogs are usually found in environments with abundant food and few predators.

Stay Always Informed

Join our communities to instantly receive the most important news, reports, and analysis from the aquaculture industry.

Coloration and General Appearance

The dorsal coloration of the American bullfrog is variable, generally ranging from olive green to brown, often with darker spots or mottling. The belly is usually whitish to pale yellow, sometimes with gray or yellowish spots. The skin is generally smooth but may have small tubercles.

A distinctive characteristic is the absence of dorsolateral folds (skin ridges along the sides of the back), which are present in many other frog species, such as the green frog (Lithobates clamitans). Instead, the American bullfrog has a skin fold that curves from the eye backward, encircling the tympanum (tympanic membrane).

Lifespan of the American Bullfrog

The lifespan of the American bullfrog can be quite long for an amphibian. In the wild, they typically live between 7 and 9 years on average, though some individuals can exceed 10 years. In captivity, with proper care and without the pressures of predation and disease, they are known to live considerably longer, potentially up to 16 years or more.

Differences Between Males and Females

There are several secondary sexual characteristics that help distinguish a male from a female American bullfrog, especially during the breeding season:

- Tympanum Size: This is the most reliable indicator. In males, the tympanum is noticeably larger than the eye. In females, the tympanum is approximately the same size as the eye or slightly smaller.

- Throat Color: Adult males often have a bright yellow throat, especially during the breeding season, whereas females’ throats are usually white or mottled.

- Nuptial Pads: Males develop dark, thickened nuptial pads on their thumbs during the breeding season, which help them grasp the female during amplexus (the reproductive embrace).

- Overall Size: Although variable, females tend to be slightly larger than males on average, though males may appear more robust due to their skull structure and the musculature associated with vocalization.

Distribution and Habitat of the American Bullfrog

Distribution

The natural range of the American bullfrog covers most of the eastern and central United States, from the Atlantic coast westward to the Great Plains, and from southern Canada (Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia) southward to northern Florida and Texas.

However, due to its popularity as a food source (frog legs), as a pet, and for “pest” control, it has been introduced into numerous areas outside its native range, including the western United States, parts of Canada, Mexico, the Caribbean, South America, Europe, and Asia. In these introduced regions, it often becomes a highly successful and damaging invasive species.

Habitat

The preferred habitat of the American bullfrog consists of large, relatively still or slow-moving permanent bodies of water, such as lakes, ponds, swamps, marshes, reservoirs, and backwaters of rivers and streams. They prefer waters with abundant emergent and submerged aquatic vegetation, which provides cover from predators and ambush sites for prey. They are quite tolerant of different water qualities but generally avoid very cold, fast-flowing, or brackish waters. The presence of permanent water is crucial, as their larval (tadpole) stage is prolonged.

Reproduction and Life Cycle of the American Bullfrog

The life cycle of the American bullfrog is a classic example of amphibian metamorphosis but with some notable peculiarities, particularly the duration of its larval stage. The life cycle of the American bullfrog consists of the following stages:

Eggs

After mating (amplexus), the female deposits a large gelatinous mass of eggs, which can contain between 1,000 and over 20,000 eggs, floating on the water surface, often attached to vegetation. The mass can cover a significant area, up to a square meter. The eggs are small, black on the top and white or cream on the bottom.

Hatching and Tadpoles

The eggs hatch within a few days (3-5 days, depending on water temperature), releasing small American bullfrog tadpoles. The tadpoles are notably large compared to those of other frogs. They can grow up to 10-15 cm (4-6 inches) or even longer before metamorphosis. They are primarily herbivorous and detritivorous, feeding on algae, decaying plant matter, and small aquatic organisms. Their coloration is typically greenish or olive with small dark spots and a creamy belly.

Duration of the Larval Stage

A distinctive feature of the American bullfrog is the long duration of its tadpole stage. Depending on latitude and water temperature, they can remain in the larval stage for a few months (in warm southern climates) up to 2 or even 3 years before completing metamorphosis. This extended larval stage is one of the reasons they require permanent aquatic habitats.

Metamorphosis

During metamorphosis, the American bullfrog tadpole undergoes drastic changes: the hind legs develop first, followed by the front legs; the tail gradually resorbs; lungs develop, replacing gills (though they retain some cutaneous respiration); and the mouth and digestive system adapt to a carnivorous diet.

Juvenile

The newly metamorphosed frog (metamorph) is a miniature version of the adult, typically measuring about 2.5-5 cm (1-2 inches). They are primarily terrestrial near water and feed on small invertebrates.

Adult

Bullfrogs reach sexual maturity in 2 to 5 years, depending on environmental conditions and growth rates. Adults are primarily aquatic or semi-aquatic and continue to grow throughout their lives, though at a slower rate after reaching maturity.

Diet of the American Bullfrog

The American bullfrog is a voracious and opportunistic predator with an incredibly diverse diet. The question, “What does the American bullfrog eat?” has a very broad answer: practically any animal it can capture and swallow.

Natural Diet of the American Bullfrog

- Invertebrates: Insects (beetles, dragonflies, grasshoppers), spiders, crayfish, snails, worms.

- Other Amphibians: Other frogs (including smaller bullfrogs), salamanders, and their larvae. They are known cannibals.

- Reptiles: Small snakes, lizards, young turtles.

- Fish: A variety of small to medium-sized fish.

- Birds: Small birds, chicks that fall into the water or nest nearby.

- Mammals: Mice, shrews, and even occasionally bats captured near the water’s surface.

Feeding in Captivity

Their diet in captivity should be varied and appropriate for their size. Juveniles can eat crickets, worms, and other insects. Adults require larger prey such as pre-killed mice (pinkies, fuzzies, adults depending on the frog’s size), large fish (such as guppies or feeder minnows), large cockroaches, and occasionally other captive-bred amphibians or reptiles if necessary (though mice are usually the staple).

Feed adults 2-3 times per week; it is crucial to supplement their food with calcium and amphibian vitamins to prevent metabolic bone disease. Avoid overfeeding to prevent obesity.

Ecology and Behavior

Activity and Thermoregulation

American bullfrogs are primarily nocturnal and crepuscular, though they can be active during the day, especially on cloudy or rainy days. They are ectothermic (“cold-blooded”), meaning they rely on external sources to regulate their body temperature. They can be seen basking on shores or floating in shallow waters to warm up and seeking shade or deeper waters to cool down. In colder regions of their range, they hibernate during the winter, usually by burrowing into the mud at the bottom of ponds or streams.

Hunting Behavior

The American bullfrog is primarily an ambush predator. It remains motionless, often partially submerged in water or hidden among vegetation, waiting for potential prey to come close. They detect movement with their large eyes and then lunge quickly, using their long, sticky tongue to catch smaller prey or pouncing and using their strong jaws and front legs to subdue larger prey. They swallow their prey whole. Their insatiable appetite and generalist diet are key factors in their success as an invasive species, as they can decimate native fauna populations.

Powerful Vocalizations of the American Bullfrog

The male American bullfrog’s call is one of its most well-known characteristics. The calls of the American bullfrog are deep and resonant, often described as a “jug-o’-rum” or “br-wum.” These calls serve various purposes:

- Mate Attraction: The primary call is used to attract female American bullfrogs to the male’s territory during the breeding season.

- Territorial Defense: Males are territorial and use their calls to warn rival males and defend their space.

- Encounter Call: They may emit a different sound if grabbed by another male.

- Alarm Call: A high-pitched squeal if captured by a predator.

Females can also vocalize, but their calls are less frequent and less powerful than those of males. The calling season usually lasts through the warm months, from spring to late summer, mainly at night, though they may call during the day as well.

Predators of the American Bullfrog

Despite their size and defensive nature, American bullfrogs have several natural predators, especially in their younger stages (eggs, tadpoles, juveniles). The main predators include:

- Eggs and Tadpoles: Large fish, dragonfly larvae, aquatic beetles, salamanders, other bullfrogs, water snakes, turtles, wading birds (herons, bitterns).

- Adults: Large snakes (water snakes, hog-nosed snakes), snapping turtles, alligators, otters, raccoons, skunks, large herons, owls, and hawks.

Humans are also significant predators, hunting them for their legs or to control invasive populations.

Conservation Status and Invasive Impact

Conservation Status

In its native range, the American bullfrog is classified as “Least Concern” by the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature). It is a common and widespread species with generally stable populations. It does not face significant threats at the species level within its natural range, though habitat degradation and pollution can affect local populations.

Impact as an Invasive Species

Outside its native range, the story is very different. The bullfrog is considered one of the world’s most problematic invasive species. Its success is due to several factors:

- Generalist Diet: They compete with and prey on a wide range of native species, including other amphibians, reptiles, birds, and small mammals. They have been known to cause significant declines and even local extinctions of native amphibians.

- Large Size and Competitiveness: They outcompete many native species for resources such as food and space.

- High Reproductive Rate: They produce large numbers of eggs.

- Resilience: They are relatively resistant to certain environmental conditions and pollutants.

- Disease Carriers: They can carry and spread devastating diseases to other amphibians, such as the chytrid fungus (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis), often without showing severe symptoms themselves. Regarding this, Hossack et al. (2023) provides empirical evidence at the landscape scale demonstrating that the presence of invasive American bullfrogs is associated with a reduction in native amphibian occurrence and an increase in the occurrence of pathogens such as the amphibian chytrid fungus (Bd) and ranaviruses in native amphibians in the southwestern United States and northern Sonora, Mexico.

Control Methods for the American Bullfrog

Efforts to control or eradicate invasive American bullfrog populations are costly, labor-intensive, and often ineffective on a large scale, though some successes have been achieved in localized areas.

Bota et al. (2024) concluded that passive acoustic monitoring combined with BirdNET software is a promising, cost-effective, and efficient tool for early detection of the American bullfrog, which could be crucial for informing management decisions and preventing the spread of this invasive species.

Preventing new introductions is crucial.

Care of the American Bullfrog

Before acquiring a bullfrog as a pet, check local and state laws. In many areas where they are invasive, it is illegal to own, breed, or release them. Always obtain animals from responsible sources and never release a pet into the wild.

Housing

American bullfrogs require a large enclosure due to their size and semi-aquatic nature. An aquaterrarium is ideal. For an adult, a tank of at least 75-100 gallons (approximately 280-380 liters) is recommended. The tank setup for an American bullfrog should include:

- Aquatic Area: A section of clean, dechlorinated water deep enough for the frog to fully submerge (at least 15-20 cm). A powerful filter is essential to maintain water quality, as they produce a lot of waste.

- Terrestrial Area: A platform or land area where the frog can fully exit the water. The substrate can be moist sphagnum moss, coconut fiber, or large gravel (too large to be ingested).

- Security: The tank lid should be secure and tightly fitted, as bullfrogs are strong and can escape.

Environmental Parameters

- Temperature: Maintain a temperature gradient. Water temperature should be 21-27°C (70-80°F). The land area can have a light heating spot (using a low-wattage heat lamp) reaching 27-29°C (80-85°F), with the rest of the land area remaining cooler.

- Nitrites: Chen et al. (2024) concluded that the American bullfrog (Aquarana catesbeiana) is sensitive to nitrites, and exposure to this contaminant, even at low concentrations (5 mg/L), can cause irreversible liver damage.

- Humidity: Maintain high humidity by misting the enclosure regularly.

- Lighting: They do not require special UVB lighting, but a full-spectrum light for 10-12 hours per day can help simulate a natural day-night cycle and promote natural behaviors.

Handling

Frequent handling is not recommended. Bullfrogs have sensitive skin and can become stressed easily. If moving them is necessary, use powder-free gloves moistened with dechlorinated water to protect their skin and prevent the transfer of oils or residues from your hands. They may bite if they feel threatened, although their bite is not medically significant for humans.

Transport

Transport boxes are an important alternative for moving live frogs. Alves et al. (2024) recommends using perforated polyethylene boxes with the following dimensions:

- 38 cm wide x 58 cm long x 22 cm high

- Covered with monofilament screens with 50% light transmission

- Each box contained 25 frogs, equating to a density of 11.706 kg per box

Comparison: American Bullfrog vs. African Bullfrog

The American bullfrog is often confused with the African bullfrog (Pyxicephalus adspersus). Although both are large, robust frogs known as “bullfrogs,” they are very different species:

Table 01: Comparison Between the American Bullfrog vs. African Bullfrog.

| Characteristic | American Bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus) | African Bullfrog (Pyxicephalus adspersus) |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | North America | Sub-Saharan Africa |

| Family | Ranidae (True Frogs) | Pyxicephalidae |

| Maximum Size | Up to ~20 cm (8 in) SVL, ~1 kg | Males up to ~24 cm (9.5 in) SVL, >2 kg |

| Appearance | Relatively smooth skin, green/brown, no dorsolateral folds, large tympanum (male) | Rough skin with longitudinal ridges/folds, green/brown, broad head, often with bony “teeth” (odontoids) in the lower jaw |

| Habitat | Primarily aquatic/semi-aquatic (permanent water) | More terrestrial, adapted to arid climates, aestivates (buries itself) during dry seasons |

| Temperament | Can be aggressive, voracious | Very aggressive, especially males; strong bite |

| Parental Care | None (beyond site selection for egg laying) | Males guard eggs and tadpoles, may dig channels to guide them to water |

| Conservation Status | Least Concern (Native), Invasive (Introduced) | Near Threatened in some areas due to habitat loss and collection |

Aquaculture of the American Bullfrog

According to Zheng et al. (2025), the American bullfrog (Aquarana catesbeiana) represents a significant opportunity for sustainable and economically viable production through the aquaculture industry. The first attempts to establish frog farms in the United States and Canada began before 1900, although many of these early efforts resembled more the collection and concentration of wild frogs rather than true closed-cycle operations (Dodd & Jennings, 2021).

Proximal Composition

The study by Ruiz Haddad et al. (2022) demonstrated that Mexican frog by-products are an interesting source of proteins and unsaturated fatty acids (Table 2), with potential for use as additives or food ingredients due to their suitable water and oil absorption, emulsification, and gelling capacities (in the case of the skin).

Table 2: Proximal Composition of the American Bullfrog (Aquarana catesbeiana).

| Parameter | Whole Frog (WF) | Legs (LF) | Skin (SF) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proximal Composition | |||

| Protein (% d.b.) | 47.6% | 88.4% | 91.1% |

| Fat (% d.b.) | 34.6% | 3.2% | 4.2% |

| Ash (%) | 10% | — | — |

| Fatty Acid Profile | |||

| Unsaturated Fatty Acids | Predominantly PUFAs | Similar proportion of PUFAs and MUFAs | Predominantly PUFAs |

| n-6/n-3 Ratio | More abundant n-6 | More abundant n-6 | More abundant n-6 |

| Main Fatty Acids | Oleic acid, palmitic acid | Oleic acid, palmitic acid | Oleic acid, palmitic acid |

| Notable Fatty Acids | 10,13-octadecadienoic acid (18:2n-5) | 10,13-octadecadienoic acid (18:2n-5) | Linoleic acid (cis-9,12-octadecadienoic) |

| Amino Acid Profile | |||

| Source of Essential Amino Acids | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| WHO Requirement Coverage (100g) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Predominant Amino Acids | Charged amino acids | Non-polar amino acids | Charged amino acids |

| Main Amino Acid | Glutamic acid | — | Glutamic acid (high content) |

Source: Ruiz Haddad et al., (2022).

Tadpole Rearing

An important aspect of tadpole rearing is the photoperiod. De León-Ramírez et al. (2021) concluded that modifying the photoperiod, starting with fewer hours of light in relation to darkness (such as 10 hours of light: 14 hours of darkness for 60 days, and 12 hours of light: 12 hours of darkness for 30 days) during the first part of the larval stage and then changing to equal hours of light and darkness, positively affects the growth and development of the tadpoles compared to a constant photoperiod.

It seems that the color of the bullfrog rearing tanks has a positive impact on growth. Reis et al. (2024) reported that tadpoles raised in blue and black tanks reached the peak of metamorphosis and transformed into frogs more quickly than those kept in white tanks. They also noted that tadpoles raised in blue and black tanks showed higher values in body weight gain, body length, body length gain, protein efficiency ratio, specific growth rate, and a lower feed conversion rate throughout the experiment.

Rearing Systems

There are different systems for rearing bullfrogs, including flooded and semi-flooded systems. Reis et al. (2022) determined that there was no influence of pen types on tadpole growth during the growth phase; however, they recommend that American bullfrogs (Lithobates catesbeianus) be fattened in flooded pens, as animals raised in this system showed better productive performance, and their homeostasis was not disrupted.

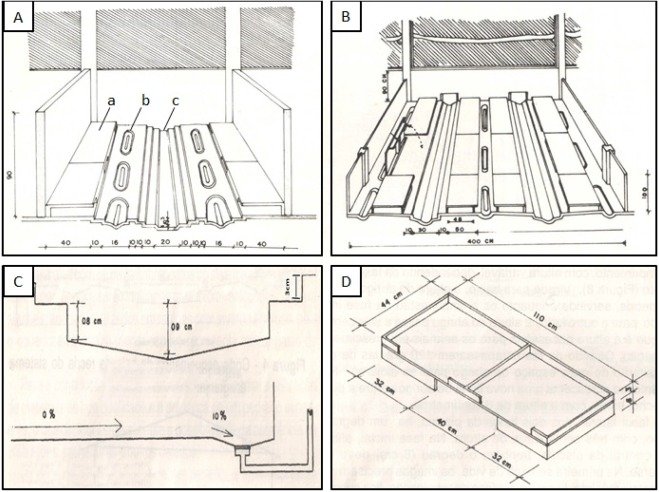

On the other hand, Pahor-Filho et al. (2019) highlight that the system known as “Anfigranja” is the most widely used production system for rearing American bullfrogs (Lithobates catesbeianus) in Brazil. This system, developed by researchers at the Federal University of Viçosa in Brazil, consists of:

Breeding Section

In this section, breeders are kept in maintenance pens (10 m²) outside the reproductive period. The pens are similar to the fattening pens but are smaller with higher shelters, a shallow pool, and feeders distributed around the pool.

Specific environmental conditions must be maintained for the development of the reproductive gonads, such as a photoperiod of 12.6/11.4 hours (light/dark), air temperature between 26 and 29 °C, and water temperature at 28 °C.

During the reproductive period, selected breeders are transferred to individual or collective mating pens for natural or hormone-induced reproduction.

Tadpole Section

The collected eggs are transferred to smaller tanks for incubation and embryonic development. Then, the tadpoles are moved to larger boxes for growth and metamorphosis, usually rectangular cement tanks with inlets and outlets for water. The tanks may have a ramp with a channel to collect the froglets at the end of metamorphosis.

Dug ponds can also be used, although they require careful monitoring of water quality.

Fattening or Growing Section

The froglets, after metamorphosis, are transferred to masonry pens (12 m²) inside a covered shed with controlled ventilation. The pens are equipped with three main elements arranged linearly: feeders, pool, and shelters.

The feeders must allow ample access to food without competition. The pool enables hydration, temperature regulation, and other physiological needs, while the shelters provide rest and refuge. Their height varies according to the growth phase of the frogs (3 cm for young frogs and 6 cm for growing and finishing frogs).

The floor has a slight slope to prevent water accumulation inside the shelters.

On the other hand, Xie et al. (2023) established an integrated wastewater treatment system for intensive American bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana) aquaculture. The system consisted of a flotation tank, a biochemical tank (primary and secondary), and constructed wetlands. The treatment system showed a significant improvement in the water quality of the wastewater from American bullfrog aquaculture.

Diseases

Streptococcosis

Di et al. (2022) reported an outbreak of Streptococcosis with high mortality rates in four American bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana) farms in Hainan province, China. According to the researchers, the main symptoms included: congestion and hemorrhage of the skin on the abdomen and hind legs, ascites, hepatomegaly, and hyperemia of internal organs.

Meanwhile, Sun et al. (2024) reported that histopathological examination of the American bullfrogs infected with Streptococcus iniae (strain STR202108) revealed lesions in multiple organs, including vacuolization in the white matter fibers of the brain, degeneration and necrosis of the intestinal mucosal epithelium, vacuolar degeneration and nuclear dissolution of hepatocytes in the liver, splenic hemorrhage and structural disappearance of the spleen, and glomerular necrosis and epithelial degeneration in the kidneys.

Ranaviruses infect a wide range of ectothermic vertebrates, including bony fish, amphibians (urodeles and anurans) (Marschang et al., 2025). This virus has been identified as the primary cause of mortality outbreaks in farmed bullfrogs in Taiwan (Hsieh et al., 2021).

Reported clinical signs included frequent skin ulcerations on the dorsal surface of the head of infected animals, cutaneous and oral hemorrhages, edema, and necrosis (Hsieh et al., 2021; Marschang et al., 2025).

Conclusion

The American bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus / Aquarana catesbeiana) is truly a remarkable creature. Its impressive size, powerful call, and adaptability make it an iconic component of North American aquatic ecosystems. The life cycle, with its prolonged tadpole stage, underscores its dependence on stable aquatic habitats.

However, its success has a dark side. Where it has been introduced outside its natural range, it has become a significant threat to local biodiversity, outcompeting and consuming native species and spreading diseases. This dual role—both a valuable member of its native ecosystem and an invasive pest elsewhere—makes it an important case study in ecology and conservation.

Whether observed in the wild, studied by scientists, or kept as a pet (with due responsibility and legal compliance), the American bullfrog demands respect and a deep understanding of its biology and ecological impact. Its story serves as a reminder of the interconnectedness of ecosystems and the consequences of moving species outside their natural boundaries.

References

Alves, A. X., Santos, N. N., Reis, G. P. A., Lana, M., Santos, B. D., Azevedo, R. O., Paulino, R. R., Costa, F. A. A., Campelo, D. A. V., & Veras, G. C. (2024, febrero 23). Transport of American bullfrogs in plastic boxes with and without moistened foam: plasma biochemistry and erythrogram responses. Research Square. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3976453/v1

Bota, G., Manzano-Rubio, R., Fanlo, H. et al. Passive acoustic monitoring and automated detection of the American bullfrog. Biol Invasions 26, 1269–1279 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-023-03244-8

Chen, Q., Zheng, X., Kumar, V. et al. Effects of nitrite exposure on biochemical parameters and liver histopathology in American bullfrogs (Aquarana catesbeiana). Aquacult Int 32, 9873–9889 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10499-024-01640-y

De León-Ramírez, J. J., García-Trejo, J. F., Gutiérrez-Antonio, C., Feregrino-Pérez, A. A., Martínez-Ramos, S. A., & Chávez-Jaime, R. (2021). Variation of Photoperiod Regime during the American Bullfrog Tadpole Stage: Influence on Growth and Metamorphosis. North American Journal of Aquaculture, 83(4), 231–239. https://doi.org/10.1002/naaq.10204

Di, Z., Zheng, J., Zhang, H., Wang, X., Guo, G., Lin, Y., Han, Q., Li, R., Yang, N., Fan, L., & Zeng, J. (2022). Natural outbreaks and molecular characteristics of Streptococcus agalactiae infection in farmed American bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana). Aquaculture, 551, 737885. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2021.737885

Dodd, C. K., & Jennings, M. R. (2021). How to raise a bullfrog—The literature on frog farming in North America. Bibliotheca Herpetologica, 15, 77-100.

Hossack, B. R., Oja, E. B., Owens, A. K., Hall, D., Cobos, C., Crawford, C. L., Goldberg, C. S., Hedwall, S., Howell, P. E., Lemos-Espinal, J. A., MacVean, S. K., McCaffery, M., Mosley, C., Muths, E., Sigafus, B. H., Sredl, M. J., & Rorabaugh, J. C. (2023). Empirical evidence for effects of invasive American Bullfrogs on occurrence of native amphibians and emerging pathogens. Ecological Applications, 33(2), e2785.

Hsieh, C., Rairat, T., & Chou, C. (2021). Detection of Ranavirus by PCR and in situ hybridization in the American bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana) in Taiwan. Aquaculture, 543, 736955. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2021.736955

Marschang, R.E. et al. (2025). Ranavirus Distribution and Host Range. In: Gray, M.J., Chinchar, V.G. (eds) Ranaviruses. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-64973-8_6

Pahor-Filho, E., Mansano, C. F. M., Pereira, M. M., & De Stéfani, M. V. (2019). The most frequently bullfrog productive systems used in Brazilian aquaculture: A review. Aquacultural Engineering, 87, 102023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaeng.2019.102023

Reis, G. P. A., Alves, A. X., Dos Santos, N. N., Da Silva, J. A., Pawlowski, V. R., Dos Santos, B. D., De Melo, D. S., Braga, N. G., Brabo, M. F., Campelo, D. A. V., & Veras, G. C. (2022). Rearing and fattening of bullfrogs (Lithobates catesbeianus) in semi-flooded and flooded systems: Productive performance and plasmatic biochemical and blood count responses. Aquaculture, 556, 738278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2022.738278

Reis, G. P. A., Dos Santos, N. N., Bezerra, V. M., Assis, Y. P. A. S., Da Silva, T. P. M., Pawlowski, V. R., Gonçalves, L. A., Braga, N. G., Lana, M., Campelo, D. A. V., De Alvarenga, É. R., & Veras, G. C. (2024). Rearing American bullfrog tadpoles in different tank colors: Effect on metamorphosis, performance, and biochemistry responses. Aquaculture, 590, 740994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2024.740994

Ruiz Haddad, L., Tejada-Ortigoza, V., Martín-del-Campo, S. T., Balderas-León, I., Morales-de la Peña, M., Garcia-Amezquita, L. E., & Welti-Chanes, J. (2022). Evaluation of nutritional composition and technological functionality of whole American Bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus), its skin, and its legs as potential food ingredients. Food Chemistry, 372, 131232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131232

Sun, J., Li, H., Lin, H., Chen, K., Qin, Z., Jiang, B., Li, W., Wang, Q., Su, Y., Huang, Y., & Liu, C. (2024). Identification and characterization of Streptococcus iniae from farmed American Bullfrogs (Aquarana catesbeiana). Aquaculture Reports, 35, 101980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aqrep.2024.101980

Xie, D. D., Hu, J. H., Lin, L. R., Huang, X. M., Xie, C. S., & He, H. B. (2023). Construction and evaluation of a tailwater treatment system for intensive aquaculture—a case study on bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana) farming.

Zhang, K., Zhang, Y., Tian, Y., Xu, B., Jiang, X., Qin, Z., Liu, C., & Lin, L. (2025). A Chromosome-level genome assembly of the American bullfrog (Aquarana catesbeiana). Scientific Data, 12(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04697-3

Zheng, X., Yang, J., Declercq, A. M., & Zhang, J. (2025). The Path Forward for China’s Bu

Editor at the digital magazine AquaHoy. He holds a degree in Aquaculture Biology from the National University of Santa (UNS) and a Master’s degree in Science and Innovation Management from the Polytechnic University of Valencia, with postgraduate diplomas in Business Innovation and Innovation Management. He possesses extensive experience in the aquaculture and fisheries sector, having led the Fisheries Innovation Unit of the National Program for Innovation in Fisheries and Aquaculture (PNIPA). He has served as a senior consultant in technology watch, an innovation project formulator and advisor, and a lecturer at UNS. He is a member of the Peruvian College of Biologists and was recognized by the World Aquaculture Society (WAS) in 2016 for his contribution to aquaculture.