Given the increasing pressure on marine ecosystems and the global demand for high-quality protein, aquaculture has evolved from an alternative into a strategic necessity. In this landscape, Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS) stand as the most disruptive and sustainable technology in the modern industry.

Unlike conventional methods, RAS allows for integrated management of the culture environment, optimizing biological growth while minimizing the environmental footprint through the recirculation of up to 99% of water resources. Moreover, RAS serves as a robust strategy for climate change adaptation; by operating in controlled indoor environments, fish and seafood production is shielded from extreme external variables such as droughts and global warming (Ahmed & Turchini, 2021).

Driven by the shift toward smart and precision production, RAS technology is set to lead a paradigm shift, gradually replacing traditional extensive models (Li et al., 2023). This technical paper explores the scientific frontiers, systems engineering, and economic viability of land-based aquaculture, providing essential insights for investors, academics, and industry professionals.

- 1 Key Points

- 2 What is a Recirculating Aquaculture System (RAS)? Concept, Evolution, and Future

- 3 Operating Principles: The Engineering Behind the RAS System

- 4 Benefits and Limitations of RAS: A Comprehensive Analysis

- 5 Scientific Trends in RAS Research

- 6 Technological Trends in RAS

- 7 Critical Components of a Recirculating Aquaculture System (RAS)

- 8 Water Quality and the Nitrogen Cycle

- 9 Ideal Species for RAS Cultivation

- 10 Design and Construction: From Artisanal Models to Precision Engineering

- 11 RAS Design Framework: Sequential Phases

- 12 Economic Viability and ROI: The Investor’s Strategic Challenge

- 13 Innovation 4.0: The Digital Future of RAS

- 14 Crisis Management and Biosecurity: Safeguarding System Integrity

- 15 Comparative Analysis: RAS vs. Traditional Systems

- 16 Conclusion

-

17

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

- 17.1 What is the fundamental difference between RAS and traditional aquaculture?

- 17.2 Which species are the most profitable for cultivation in these systems as of 2026?

- 17.3 How does Artificial Intelligence (AI) impact the management of a modern RAS?

- 17.4 What are the primary economic challenges for an investor in a Recirculating Aquaculture System?

- 17.5 Is it possible to eliminate the “earthy” taste (off-flavor) in fish raised in RAS?

- 17.6 How is biosecurity ensured in such a high-density environment?

- 17.7 Is a home-scale recirculating aquaculture system profitable?

- 18 References

- 19 Entradas relacionadas:

Key Points

- Resource Sovereignty and Water Efficiency: RAS technology enables up to 99% water reuse, decoupling aquaculture production from natural water bodies. This allows for the installation of farms near major consumption hubs, significantly reducing logistics costs and the carbon footprint associated with transport.

- Precision Aquaculture 4.0: The integration of Artificial Intelligence (such as the FeedingMonitor model) and next-generation sensors has transformed aquaculture into a data-driven discipline. The use of predictive algorithms optimizes feeding, reduces waste, and ensures biomass health through real-time monitoring.

- Climate Change Resilience: By operating in fully controlled indoor environments, RAS systems are immune to extreme external variables like droughts, floods, or ocean warming. This biological containment ensures stable and predictable year-round production.

- Economic Challenges and Process Optimization: Although CAPEX and OPEX remain high, financial viability is achieved through economies of scale and stochastic optimization approaches. The transition to hybrid energy systems (Photovoltaic Aquaculture) is the cornerstone of profitability and sector decarbonization in 2026.

- Biosecurity as a Critical Asset: The ability to isolate cultures from external pathogens and parasites eliminates the need for chemical antibiotics. However, system stability requires engineering redundancy protocols and independent life-support systems to mitigate high-density operational risks.

What is a Recirculating Aquaculture System (RAS)? Concept, Evolution, and Future

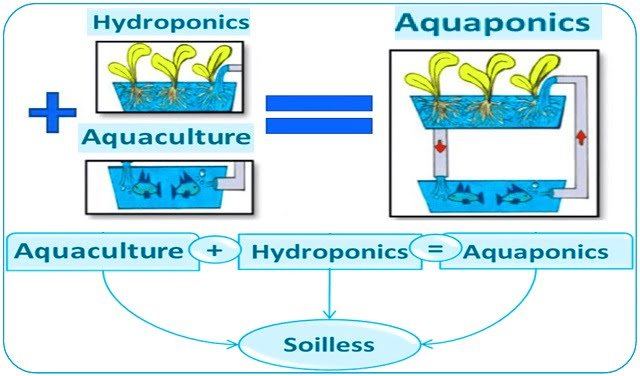

Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS) represent the technological vanguard of aquatic production, enabling intensive farming through nearly total water reuse. Unlike open-water methods (marine cages) or semi-open systems (flow-through ponds), this infrastructure cyclically filters and purifies water to reintroduce it into culture units under optimal conditions.

Technically, RAS are defined as land-based controlled ecosystems that employ advanced mechanical and biological filtration for the grow-out of fish, crustaceans, and mollusks. This closed-loop system ensures total control over critical parameters—such as temperature, oxygen levels, and biosecurity—effectively shielding production from external climatic fluctuations.

Historical Evolution and Strategic Significance

According to Ahmed and Turchini (2021), pioneering research on this technology dates back to 1950s Japan. However, its technical maturity was forged in Europe during the 1970s:

- Germany: Demonstrated the technical feasibility of intensive carp production.

- Denmark: Led the development of engineering components through its Aquaculture Institute, fostering the system’s commercial vision by the mid-1970s.

Commercialization and Global Expansion

Industrial deployment consolidated between the 1980s and 1990s, with Europe as the epicenter. A key milestone occurred in 1980 when Denmark launched the first commercial system designed for the European eel (Anguilla anguilla). This success drove adoption in the Netherlands for catfish and other species during the 90s. Simultaneously, North America initiated its own R&D programs, while China ventured into marine recirculation systems.

Today, the integration of smart sensors and digital twins has transformed these farms into biological data centers. The mass adoption of RAS addresses the imperative need for production near consumption hubs, drastically reducing logistics costs and the carbon footprint associated with global transport.

Operating Principles: The Engineering Behind the RAS System

The operational foundation of a Recirculating Aquaculture System (RAS) lies in the continuous, cyclic management of effluents. Its primary objective is to neutralize toxic metabolites resulting from biological activity—chiefly ammonia and carbon dioxide—and to restore the oxygen levels depleted by the biomass. According to Malone (2013), the efficiency of any RAS depends on the synergistic integration of five treatment engineering pillars: circulation, clarification (solids removal), biofiltration, aeration, and CO2 stripping.

Stay Always Informed

Join our communities to instantly receive the most important news, reports, and analysis from the aquaculture industry.

To maintain system homeostasis, a standard model follows this logical treatment flow:

- Thermoregulation: Precise thermal adjustment via heat exchangers to maximize growth efficiency based on the species’ requirements.

- Culture Unit: The primary tank designed for biomass support and controlled feed administration.

- Clarification and Solids Removal: Application of mechanical filtration to extract feces and organic waste, preventing water quality degradation.

- Biofiltration (Nitrifying Cycle): A bacterial conversion process where toxic ammonia is transformed into nitrate, a compound with significantly lower biological risk.

- Degassing: A critical phase for removing accumulated carbon dioxide, thereby preventing acidification of the medium.

- Oxygenation and Aeration: Injection of pure oxygen or forced aeration to maintain optimal levels that sustain metabolic growth.

- Safety Disinfection: Treatment via UV radiation or Ozone for pathogen neutralization and biosecurity control.

Benefits and Limitations of RAS: A Comprehensive Analysis

According to Ahmed and Turchini (2021), RAS systems represent a paradigm of ecological efficiency. Their ability to generate high biomass densities within reduced water volumes mitigates adverse impacts such as habitat destruction, eutrophication, and water pollution. Furthermore, their closed design ensures superior biosecurity levels, drastically reducing reliance on antibiotics.

This technology allows for absolute governance over production variables—temperature, oxygen, and pH—resulting in stable, predictable growth and notable pathogen resilience (Bregnballe, 2015). Recent studies, such as those by Deng et al. (2022), confirm that species like Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) exhibit significantly higher survival rates in RAS compared to Flow-Through Systems (FTS).

However, as noted by Brown et al. (2025), while control is absolute, the technical and economic hurdles remain substantial.

Competitive Advantages

- Resource and Location Optimization: The capacity to recirculate up to 99% of water allows farms to be situated near consumption hubs (urban or inland areas). This reduces “food miles” and the logistical carbon footprint.

- Ecosystem Protection: By operating on land, critical risks to the marine environment—such as sea lice infestations, fish escapes (genetic pollution), or disease transmission to wild populations—are eliminated.

- Metabolic Efficiency: RAS specimens show an optimized Feed Conversion Ratio (FCR) (averaging 1.125) compared to those raised in traditional cages (1.264).

- “Post-Smolt” Strategy: Utilizing RAS to rear larger juveniles (0.5 to 1 kg) before sea transfer halves the exposure time to oceanic environmental risks.

Operational Challenges and Constraints

- Scale Risks: Intensive farming is prone to mass mortality events if biosecurity barriers fail, necessitating operational stability and economies of scale of at least 5,000 tonnes annually to ensure profitability.

- Energy Intensity: Land-based electricity consumption is currently three times higher than that of marine cages; these GHG emissions represent a critical disadvantage for climate change mitigation (Ahmed & Turchini, 2021).

- Water Quality Complexity: Managing metabolites in seawater is complex; CO2 removal is less efficient, and there is a risk of highly toxic hydrogen sulfide formation.

- Sensory Profile (Off-flavor): The accumulation of geosmin produced by bacteria in biofilters can alter the product’s taste. Mitigation requires costly purging processes that involve biomass and lipid loss.

- Precocious Maturation: The “grilse” phenomenon (early maturation) affects meat quality and can lead to economic losses of up to 10% due to reduced immune function.

Scientific Trends in RAS Research

For the analysis of scientific trends, 1,054 scientific documents centered on Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS) were retrieved from Scopus. The study period spans from 2015 to early 2026 (including articles in press and early access), providing a comprehensive view of the industry’s dynamics over the last decade.

National Thematic Focuses

The analysis reveals that RAS research is not uniform; each nation approaches the system based on its industrial needs and technological capabilities:

- China (Absolute Leader – 311 docs): Research is primarily biotechnical and microbiological. Focus areas include growth, stocking density, and, crucially, the study of bacterial and microbial communities within the system to optimize denitrification.

- United States (106 docs): The emphasis is on technology and product quality. Key research involves Atlantic Salmon and the removal of off-flavor compounds such as geosmin and 2-methylisoborneol (MIB), which are essential for commercial acceptance in premium markets. In this regard, Ranjan et al. (2026) demonstrated that High-Field Asymmetric Waveform Ion Mobility Spectrometry (FAIMS) has the potential to effectively distinguish between “clean” salmon fillets and those contaminated with geosmin.

- Norway (70 docs): Specialized in Atlantic Salmon and physiology. Research focuses on fish health, salinity management, and alkalinity, aiming to optimize smoltification phases in closed systems.

- Germany (66 docs): A leader in integrating RAS with Aquaponics and using advanced disinfection technologies like ozone. Research is highly oriented toward sustainability and the circular economy.

- Indonesia & India (64 docs): Focused on basic engineering and water quality. Studies center on biofilter efficiency, nitrification, and the adaptation of systems for local species such as shrimp and Asian sea bass.

- Brazil (54 docs): Notable for research on neotropical species (Tambaqui) and the integration of RAS with Biofloc Technology (BFT), seeking low-cost, high-efficiency solutions for tropical climates.

Leading Institutions and Their Strategic Research Streams

By cross-referencing validated institutions with scientific publication data, we have identified the following strategic specializations:

- Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences (CAFS) & Ocean University of China: Their focus is production-oriented and biotechnological. They lead research in dietary optimization for RAS, stocking density management, and bacterial disease control—applied science specifically aimed at food sovereignty.

- Ministry of Education/Agriculture (China): These affiliations typically represent university consortia. Their primary focus is system microbiology, specifically the study of biofilters and microbial communities for nitrogen removal.

- Freshwater Institute Shepherdstown (USA): Their research stream lies in Engineering and Welfare. They are global benchmarks in the physical design of RAS and in studies regarding the stress and health of Atlantic Salmon in closed environments.

- Technical University of Denmark (DTU): Specializing in Water Treatment and Chemistry. They are noted for their studies on disinfection (ozone, UV) and the dynamics of residual organic matter within the system.

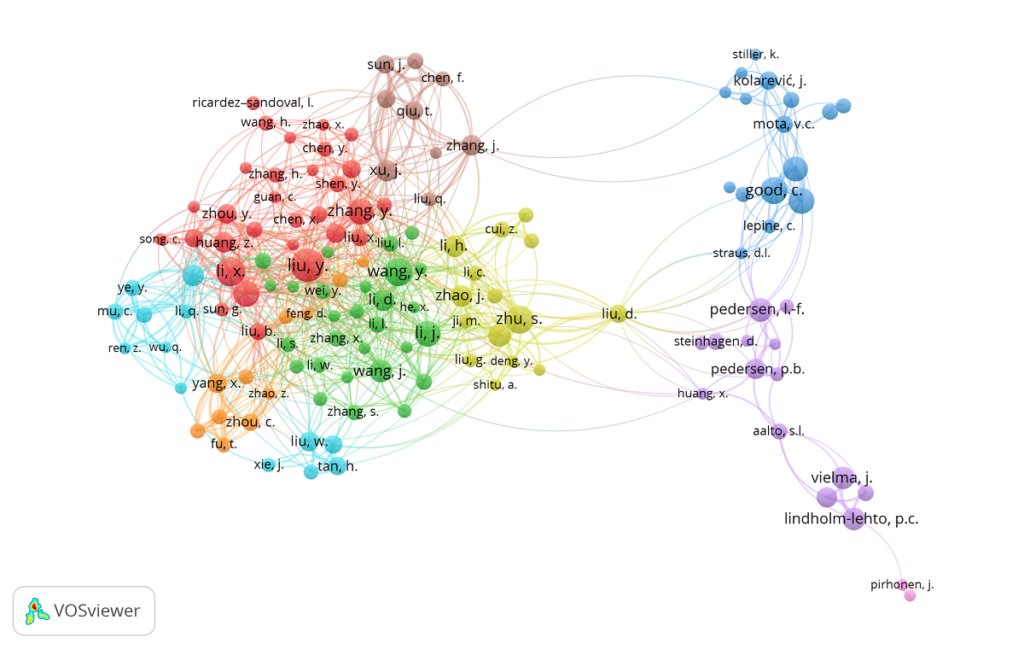

Dynamics of Collaboration Networks

The map presented in Figure 01 reveals a “small-world” network structure with evident geographic polarization, yet featuring critical points of technical integration:

- The Eastern Bloc (Red and Green Clusters): The Intensification Core

- Leaders: Liu, Y., Wang, Y., and Zhang, Y.

- Dynamics: This is a high-density network. These authors frequently co-publish on the dynamics of bacterial communities in moving bed biofilter systems and the optimization of nitrification.

- Insight: The proximity of these nodes suggests shared laboratory infrastructures or membership in large national consortia (such as the Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences) that dominate volume-based production.

- The Western Bloc (Blue Cluster): Welfare and Product Quality

- Leaders: Good, C. and Mota, V.C.

- Dynamics: A more dispersed network is observed, indicating transatlantic collaborations (USA, Norway, Denmark).

- Insight: Their output focuses on Atlantic Salmon health, the use of disinfection technologies—such as peracetic acid (PAA)—and geosmin removal. They represent the industrial branch oriented toward premium markets. Good et al. (2022) demonstrated that PAA is effective in eliminating populations of three major bacterial fish pathogens (Yersinia ruckeri, Weissella ceti, and Flavobacterium columnare) in RAS water.

- The Yellow Cluster: The Knowledge “Gatekeepers”

- Key Actors: Zhu, S. and Liu, D.

- Strategic Analysis: These authors frequently publish in high-impact global engineering journals (such as Aquacultural Engineering).

- Role: They act as intermediaries because their research centers on the fundamentals of RAS engineering (hydraulic design, flow modeling, energy consumption)—topics that are universal and of interest to both the Eastern and Western blocs. They facilitate the flow of knowledge between both spheres.

- The Violet Cluster: Nutrition Specialization

- Actors: Vielma, J. and Lindholm-Lehto, P.C.

- Specialization: There is a strong focus on sustainable nutrition and the use of alternative protein sources in aquafeeds specifically designed for RAS. Their peripheral position indicates a specialization that, while necessary, is not the central axis of system engineering.

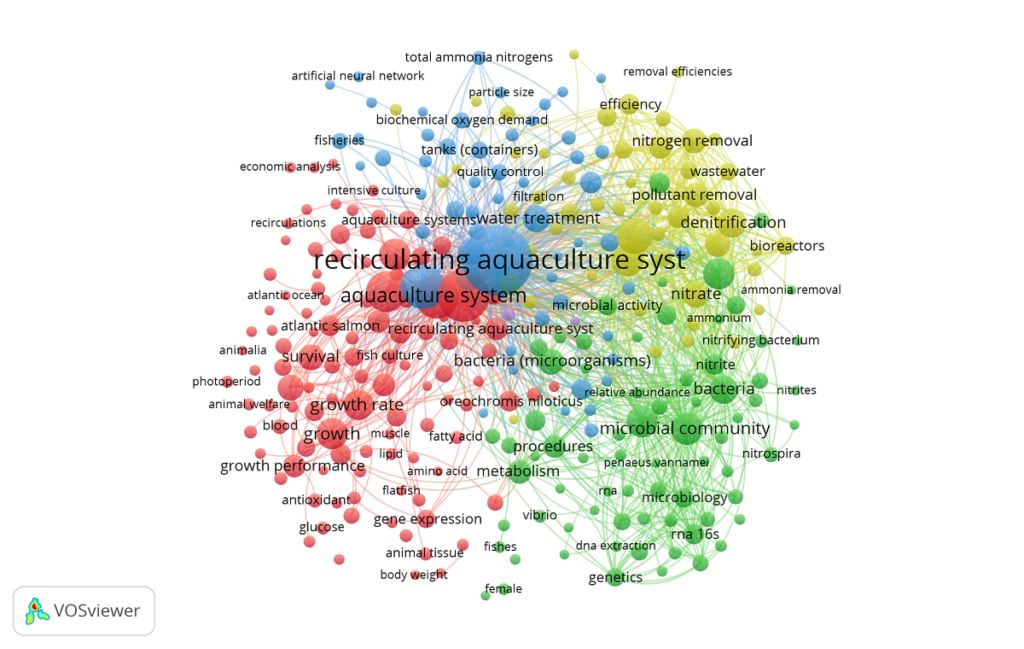

Thematic Knowledge Map

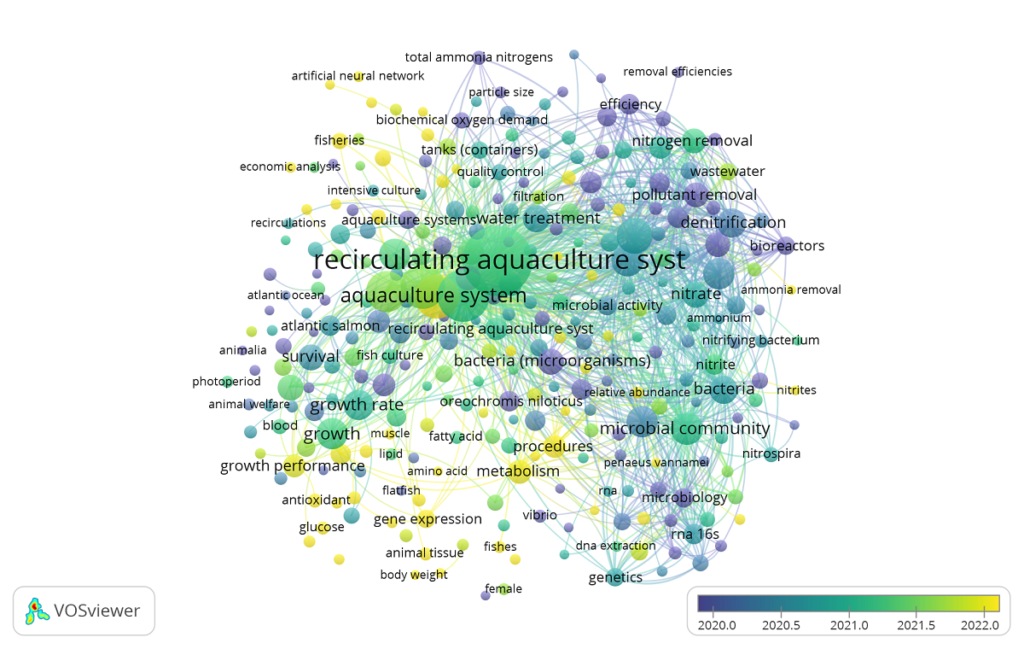

The keyword co-occurrence analysis presented in Figure 02 reveals that RAS research has evolved from a purely mechanical discipline into a multidisciplinary and convergent field.

Table 01. Four research fronts in Recirculating Aquaculture Systems.

| Cluster | Designation | Strategic Focus | Key Technologies |

| Red | Biological Optimization | Maximizing fish/salmon yield and welfare. | Gene expression, lipid analysis, stress biomarkers. |

| Green | Microbial Intelligence | The biofilter as a “living organ” of the system. | 16S rRNA sequencing, metagenomics, Nitrospira management. |

| Blue | Engineering 4.0 | Automation and precision control. | Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), real-time sensors, fluid dynamics. |

| Yellow | Circular Economy | Effluent remediation and sustainability. | Denitrification, nitrogen recovery, wastewater treatment. |

The emergence of “Artificial Neural Networks” (Blue Cluster) in 2024-2025 academic literature indicates that RAS is entering the era of Precision Aquaculture. It is no longer sufficient to merely filter; the objective now is to predict system failures through AI. Furthermore, the Green Cluster (Microbiology) shows a transition from classical bacteriology to Metagenomics, focusing on designing bespoke microbial communities to prevent pathogens.

Anchor Species:

- Atlantic Salmon: Drives the high-tech and physiology cluster.

- Tilapia (O. niloticus): Serves as the model species for denitrification and biofloc studies due to its resilience.

- Shrimp (P. vannamei): Fuels research into gut health and microbiota within closed-loop systems.

Emerging Trends and the Future of the Field

Temporal analysis reveals that the RAS field has reached “technical maturity” and is now shifting toward “operational excellence.”

Table 02. Emerging trends in Recirculating Aquaculture Systems research.

| Dimension | Consolidated Topics (Past/Blue) | Emerging Topics (Future/Yellow) |

| Technology | Simple mechanical and biological filtration. | Artificial Intelligence (ANN) and Digital Twins. |

| Animal Health | Survival and general growth rates. | Nutrigenomics, oxidative stress, and gene expression. |

| Management | Nitrogen and Ammonium removal. | Economic analysis and profitability optimization. |

Disruptive Fronts (2024–2026)

The most recent data and Figure 03 highlight three pillars defining future research and investment:

- Aquaculture 4.0 (The Digital Frontier): AI is now used for proactive management, such as predicting nitrite spikes before they occur. Notably, Liu et al. (2026) developed the CS-TransNeXt model for fish feeding intensity scoring, achieving a superior Top-1 accuracy of 95.25% and an F1-Score of 95.30%.

- The Biofilter “Holobiont”: Research has shifted from individual bacteria to the microbial community as a whole. The trend is to manage the microbiome to suppress pathogens through biological competition, reducing the need for chemical disinfectants.

- Precision Metabolism: The focus on amino and fatty acids indicates that RAS is becoming a nutrition laboratory. The goal is to design diets that minimize solid waste while optimizing meat quality, texture, and flavor.

This study illustrates that the RAS sector is undergoing an exponential expansion phase driven by China in terms of production volume, while technical sophistication is co-championed by Western hubs (USA, Norway, and Denmark). Technology scouting indicates that future commercial viability will hinge not on filtration capacity alone, but on the seamless integration of data science (AI) with molecular welfare (Genomics).

Disruptive Technological Trends in RAS

Based on the scientometric analysis and technology scouting conducted on a corpus of 1,054 documents (2015–2026), five disruptive technological trends have been identified as redefining the field of Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS). The overarching trend is the transition of RAS from a mere “filtration infrastructure” to a “digitally controlled biotechnological ecosystem.”

Precision Aquaculture and Artificial Intelligence (AI)

This is the trend exhibiting the most significant growth within the “yellow nodes” (representing the most recent data) of the temporal map.

- Artificial Neural Networks (ANN): These are being integrated for predictive water quality control. Unlike traditional sensors that only record the present, AI models allow for the forecasting of ammonia spikes or oxygen depletion before they manifest.

- Digital Twins: This involves the creation of virtual replicas of the RAS to simulate biological load scenarios and power failures, thereby optimizing the system’s design prior to physical implementation.

Microbiome Engineering (The “Omic” Biofilter)

There is a noticeable shift from the study of “simple nitrification” toward the complex management of microbial communities.

- Metagenomics (16S rRNA): The use of genetic tools to monitor, in real-time, the bacterial populations inhabiting the system. In this regard, Krishna et al. (2026) reported that environmental DNA or environmental RNA (eDNA/eRNA) analysis in water samples serves as a suitable, non-lethal, and non-invasive alternative to tissue sampling—which necessitates sacrificing fish—for the early detection and monitoring of pathogens such as SGPV (Salmon gill poxvirus), ISAV-HPR0 (Infectious salmon anaemia virus), IPNV (Infectious pancreatic necrosis virus), PRV-1 (Piscine orthoreovirus genotype 1), and the bacterium Flavobacterium psychrophilum.

- Designer Microbiomes: Rather than allowing bacteria to colonize the biofilter at random, the current trend favors selective inoculation to suppress pathogens (such as Vibrio) through biological competition, thereby reducing antibiotic dependency.

Nutrigenomics and Molecular Physiology

As validated in the red and yellow clusters, the research focus has shifted from mere “growth” toward comprehensive “metabolic health.”

- Oxidative Stress Markers: Research into how tank hydrodynamics influence fish gene expression and physiological response.

- RAS-Specific Diets: Development of high-digestibility feeds designed to produce firmer, larger fecal pellets. This facilitates efficient mechanical removal and prevents particles from dissolving and clogging the biofiltration system.

Advanced Denitrification and the Circular Economy

Environmental sustainability has shifted from a mere regulatory requirement to a core technological driver.

- Heterotrophic Denitrification Systems: Designed to eliminate nitrates (NO3) in “zero-exchange” or “zero-recharge” systems, enabling water savings of up to 99%.

- Sludge Recovery: Technologies aimed at converting RAS organic waste into fertilizers for aquaponics or substrates for biogas production, effectively closing the nutrient loop.

- Microalgae Integration: Algae function as “living purifiers,” assimilating ammonia, nitrate, and phosphate while generating oxygen and consuming CO2, which reduces the need for mechanical aeration during daylight hours.

- Hybrid Systems (RAS + Biofloc/Symbiotic): In Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) cultivation, symbiotic systems (biofloc + probiotics) achieved the highest survival rates (90%) and yields, outperforming both pure RAS and traditional biofloc models.

- Aquaponics: Research confirms that consumers are willing to pay a premium for aquaponic products when marketed as sustainable and pesticide-free.

System Hybridization (RAS + Biofloc)

This approach is particularly prominent in the production of Pacific white shrimp (P. vannamei) and tropical species across Brazil and Indonesia.

- Mixed Systems: These systems integrate the reliability of RAS mechanical filtration with the in-situ nutrient recycling capabilities of Biofloc Technology (BFT). This synergy significantly reduces operational energy costs, which have historically represented the “Achilles’ heel” of conventional RAS.

Technological Trends in RAS

The analysis is based on a corpus of 828 patent documents related to recirculating aquaculture systems retrieved from the Lens platform. The database spans from 2015 to early 2026.

Geography and National Thematic Focuses

After validating the top 10 countries, the International Patent Classification (IPC) and abstracts were analyzed to determine technical specializations:

- China (CN) — “The Engineering Workshop”: Strongly specializes in A01K63 (Apparatus for treating water in ponds). Its focus is predominantly on hardware and systems engineering, with a high concentration of patents dedicated to aquaculture-specific wastewater purification (C02F103).

- United States (US) — “Nutrition and Biological Management”: Although a leader in tank system design, it specifically excels in A23K10 (Animal feeds and additives). This indicates that the U.S. industry prioritizes nutritional efficiency and the organism’s life cycle within the RAS environment.

- European Patent Office (EP) & WIPO (WO) — “Industrial-Scale Systems”: International applications reveal a trend toward automation and quality control, with developments focused on scalability and standardization for global markets.

Leading Institutions and Their Research Streams

The leading institutions in terms of patent registrations linked to Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS) include:

- ATLANTIC SAPPHIRE IP LLC (Company – Denmark/USA): Their technology focuses on large-scale fish transfer and logistics systems. They are pioneers of the “Bluehouse” concept, optimizing biomass movement within massive land-based facilities.

- GRAINTEC AS (Company – Denmark): Specialists in integrated water flow and feeding design. Their focus lies in operational efficiency and the hydraulic transport of feed within the RAS.

- ZHEJIANG UNIVERSITY (University – China): Represents the academic arm with high innovation in 3D multi-layer systems for mollusks (Babylonia areolata) and flow control based on mRNA responses—a highly advanced biotechnological frontier.

- CAN TECH INC & PRAIRIE AQUATECH (Companies – Canada/USA): Both specialize in the intersection of feeding and water quality. They develop fecal binders and microbial protein concentrates to minimize waste load within the RAS.

- ROYAL CARIDEA LLC (Company – USA): Their research focus is exclusive to multi-phase super-intensive shrimp production, a highly profitable niche.

- TECHNION RES & DEV FOUNDATION (Institute – Israel): Leaders in water chemistry, specifically in the removal of nitrogenous species (ammonia/nitrites) through physicochemical processes, which are critical for recirculation in saline waters.

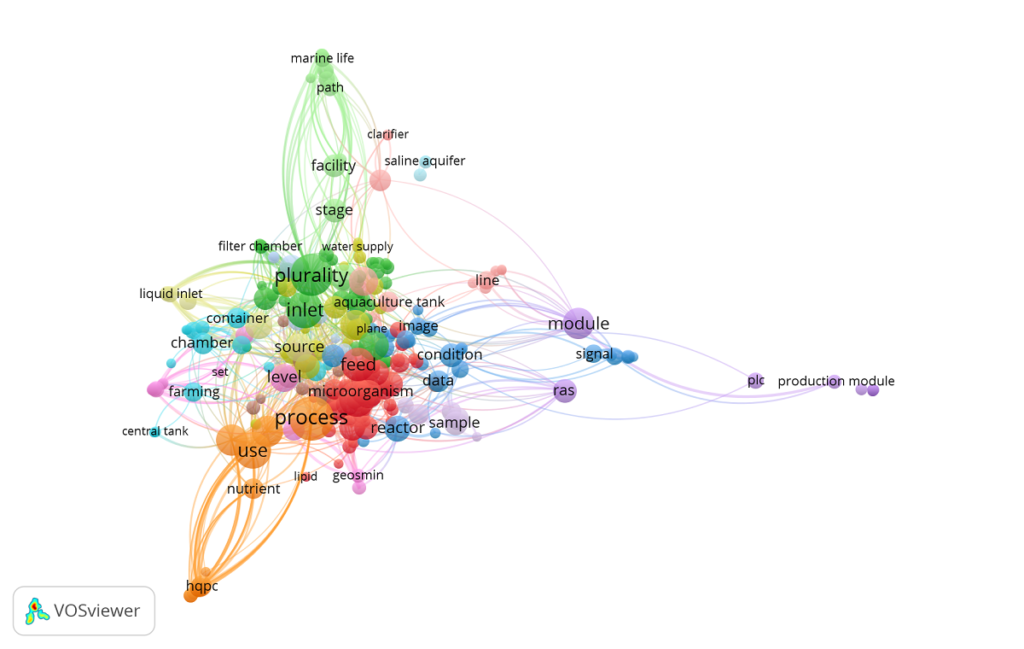

Thematic Knowledge Map

Based on the keyword co-occurrence within the bibliometric map in Figure 4 and its cross-reference with the patent database, the intellectual structure of the RAS field is divided into five research fronts:

The Bioengineering Core (Red Cluster – Processes and Feeding)

This serves as the central pillar of the map. Patents in this domain (led by firms such as Prairie AquaTech and Kiverdi) move beyond simple fish production to focus on the precise control of the microbial ecosystem.

- Critical Focus: The term “geosmin” is paramount. It signals significant patenting activity aimed at eliminating off-flavor metabolites, which remains a critical hurdle for the commercial viability of land-based RAS.

- Components: Biological reactors and lipid synthesis for nutrition.

Fluid Engineering and Design (Green Cluster – Infrastructure)

This cluster represents the physical foundation where industry leaders like Graintec and Atlantic Sapphire dominate.

- Critical Focus: Innovations in the configuration of inlets and tank geometries aimed at optimizing hydrodynamics.

- Insight: The recurrent use of the term “plurality” reflects a strategic trend toward securing patent protection for complex systems comprising multiple modular components.

Aquaculture 4.0 (Blue and Violet Clusters – Digitalization)

This represents the area with the most expansion toward the periphery, identifying it as the technological frontier.

- Critical Focus: Integration of PLCs (Programmable Logic Controllers) and data signals. This domain includes Zhejiang University’s patents, which link control algorithms to biological responses (signals).

Filtration and Containment (Cyan Cluster – Physical Purification)

This front focuses on mechanical efficiency.

- Critical Focus: Filtration chambers and containment vessels. This is the area where Pentair and Ecolab concentrate their efforts to ensure water clarity and sanitation through solids-retention hardware.

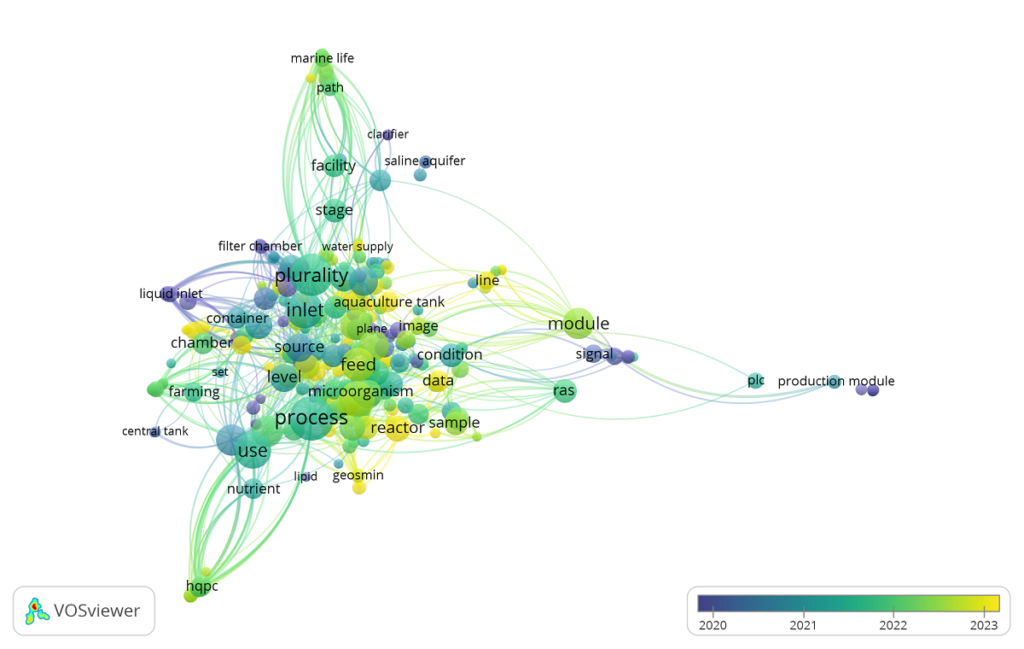

Emerging Trends and the Future of the Field (2020–2026 Analysis)

The VOSviewer overlay visualization map in Figure 05 reveals an “Innovation Roadmap” that has transformed RAS from a civil engineering project into a smart digital ecosystem.

Table 03. Chronological evolution of RAS patenting.

| Temporal Phase | Technological Focus | Key Terms (VOSviewer) | Status in 2026 |

| Phase 1: Foundations (2020) | Hardware and Basic Automation | PLC, container, chamber, signal | Commodity: These are standard technologies; competitive advantage no longer resides here. |

| Phase 2: Maturity (2021-2022) | Bioprocesses and Stability | Microorganism, nutrient, process | Consolidation: Microbiome control is now the operational “heart” of any industrial RAS plant. |

| Phase 3: Vanguard (2023-2026) | Intelligence and Data (Precision Aquaculture) | Image, data, sample, reactor optimization | Frontier: This is the current highest-growth area, focusing on the “software layer” above the hardware. |

Analyzing the Vanguard: The Era of Computer Vision

As the map analysis clearly indicates, the shift toward yellow (2023+) marks the arrival of Precision Aquaculture:

- Computer Vision (“Image” Node): Current patents no longer merely measure chemical parameters; they “observe.” The use of underwater cameras and deep learning algorithms to detect feeding behavior in real-time has allowed for a reduction in feed waste by 30–35% as of 2026.

- Data Management and Optimization: The convergence of “data” and “feed” nodes confirms that the future of RAS is algorithmic. We are witnessing a transition from reactive systems (measuring and correcting) to predictive systems (anticipating water quality crises before they occur).

2026 Perspective: Toward the “Blue Transformation”

Today, the trends that were “yellow” in 2023 have branched into:

- Digital Twins: Virtual replicas of RAS facilities used to simulate stress scenarios without putting biomass at risk.

- Genetic Traceability and Blockchain: Integration of health data from egg to harvest, ensuring full transparency for the end consumer.

Strategic Note: Companies or researchers looking to enter the market today must focus on data interoperability. The hardware has already been invented; the current value now lies in the intelligence that manages it.

Technological Trends in Patents

Based on a comprehensive analysis of patent metadata and the interpretation of VOSviewer mapping, technological trends in Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS) are categorized into three distinct dimensions:

Chronological Evolution (The Technological “Roadmap”)

The study reveals a clear shift in innovation focus through three developmental stages:

- The Past (2020) – Physical Infrastructure: Innovation was centered on basic hardware, including tank design, filtration chambers, clarifiers, and primary automation using PLCs (Programmable Logic Controllers).

- Transition (2021–2022) – Biological Optimization: The focus shifted toward microbiome control, nutrient management, and water chemistry stability to ensure biomass survival.

- Present and Future (2023–2026) – Intelligence and Data: The current vanguard of the industry is Precision Aquaculture. Modern patents have shifted their focus toward the “software layer,” emphasizing computer vision for fish monitoring, Big Data analytics for feeding regimes, and the algorithmic optimization of reactors.

Key Breakthroughs in Algorithmic Management

- Precision Feeding for Fry (Yang et al., 2025): This research successfully implemented a precision feeding method for fry in RAS, which enhances feeding efficiency and promotes fish growth more effectively than traditional manual methods.

- The FeedingMonitor Model (Wang et al., 2026): This advanced system is based on computer vision and the Transformer in Transformer (TNT) architecture. It allows for the precise, real-time evaluation of feeding intensity within RAS environments.

Impact on Operational Efficiency

The study concludes that FeedingMonitor can quantify feeding behavior and calculate a specific Feeding Intensity Index (FII) to guide automated feeding machinery.

- Dynamic Adjustment: The FII allows the system to adjust the recommended feed amount dynamically.

- Waste Prevention: By avoiding both overfeeding and underfeeding, the system prevents water quality degradation and resource waste.

- Animal Welfare: Optimal feeding leads to improved production efficiency and significantly higher standards of fish welfare.

Innovation Clusters

Five critical areas have been identified where intellectual property is concentrated:

- Biotechnology and Organoleptic Quality: A prominent trend involves the elimination of geosmin (responsible for off-flavors in fish) and the utilization of microorganisms to synthesize proteins and lipids within the system (C1 substrates).

- Fluid Engineering 4.0: Innovation in water inlets and multilayer or 3D systems (pioneered by China) to maximize production within confined spaces.

- Advanced Nitrogen Management: Development of complex physicochemical processes for the removal of nitrogenous compounds, which are particularly critical in saline water systems.

- Functional Nutrition for RAS: Patents for feed containing “fecal binders” that facilitate mechanical filtration and prevent biofilter collapse.

Geographic Specialization (Investment Hotspots)

- China: Leads the Scalability and Hardware trend, focusing on large-scale infrastructure and physical filtration systems.

- United States: Dominates the Bioprocesses and Nutrition sector, prioritizing biological efficiency and end-product quality.

- Europe: Specializes in Standardization and Precision Engineering, with a strong emphasis on operational sustainability.

Summary of “Hot Topics”

For current investment or research initiatives, the following areas demonstrate the highest growth and strongest intellectual property protection:

- Computer Vision (Image Analysis): Utilized for health monitoring and biomass estimation.

- Biofilter Optimization (Reactors): Achieving superior efficiency within a reduced footprint.

- Logistics Transfer Systems: Automated, stress-free fish movement between tanks (pioneered by leaders such as Atlantic Sapphire).

- Genetic/mRNA Monitoring: Sensors designed to quantify biological responses to the RAS environment.

In conclusion, the overarching trend is the digitalization of the biological environment; a robust filtration system is no longer sufficient—it is now imperative to employ systems that “understand” and “visualize” aquatic conditions in real-time.

Critical Components of a Recirculating Aquaculture System (RAS)

To fully comprehend the structural architecture of a Recirculating Aquaculture System, it is essential to deconstruct its core engineering components.

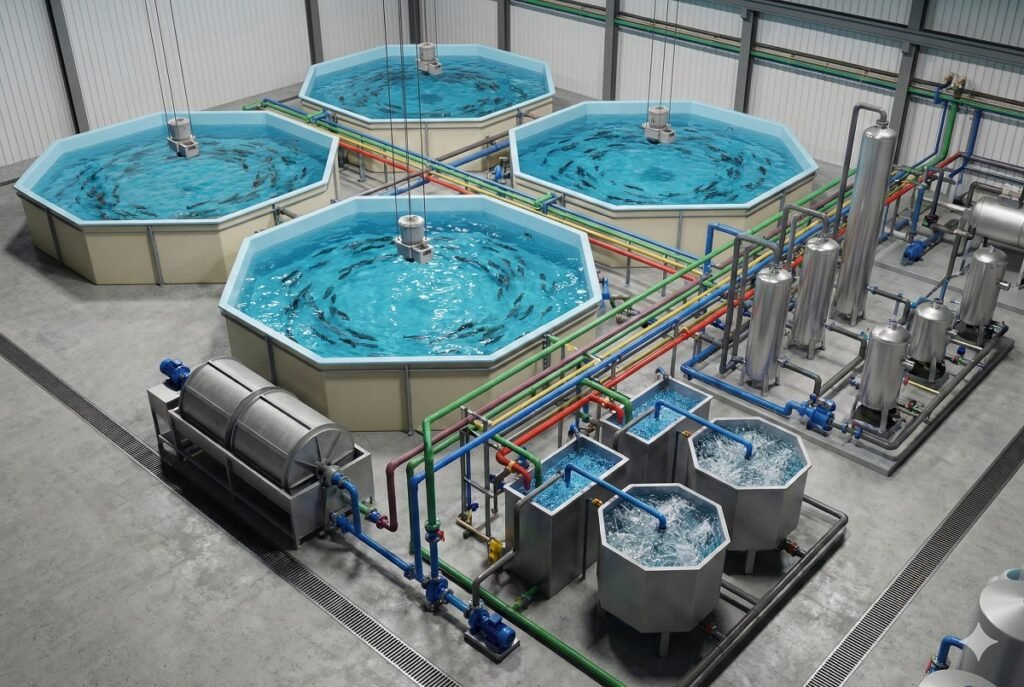

Culture Tanks

Tank geometry is a critical determinant of both hydrodynamic behavior and self-cleaning efficiency. Circular tanks are predominantly utilized in RAS design due to their capacity to generate a steady rotational flow; this vortex effect concentrates suspended solids at the central axis, thereby facilitating streamlined extraction through the primary drain.

Mechanical Filtration (Solids Removal)

Suspended solids represent the primary adversary of the biofiltration process. The industry standard is the drum filter, which utilizes specific micron-rated meshes (typically 40 to 80 microns) to sequester particulate matter before it degrades and introduces additional ammonia into the system.

Biofiltration: The System’s Vital Center

Biofilters in RAS function as biological reactors that host nitrifying bacteria—specifically Nitrosomonas and Nitrobacter.

- Moving Bed Biofilm Reactor (MBBR): This system employs buoyant plastic media with a high specific surface area to support biofilm development; it is the industry benchmark due to its minimal maintenance requirements.

- Fixed Bed Filters: These are typically utilized in smaller-scale operations or systems characterized by lower organic loads.

Degassing and CO2 Management

As stocking density (kg/m3) escalates, carbon dioxide concentrations increasingly become a limiting factor. Degassing columns, or stripping towers, leverage air-water interface contact to expel CO2 into the atmosphere. Elevated CO2 levels acidify the aqueous environment, suppressing pH levels and inducing physiological stress in the biomass.

To conceptualize the functionality of a Recirculating Aquaculture System, it must be viewed as a living organism, where each engineering component acts as a vital “organ” within a larger filtration anatomy.

Table 04. Principal Components of Recirculating Aquaculture Systems

| Component | Technical Function | Impact on Production |

| Culture Tank | Hydrodynamics and primary solids removal. | Maximizes stocking density (kg/m3). |

| Drum Filter | Mechanical removal of particles >40 microns. | Reduces Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD). |

| Biofilter (MBBR) | Conversion of ammonia (NH3) into nitrate (NO3). | Prevents lethal toxicity from nitrogenous compounds. |

| Degasser | Removal of accumulated carbon dioxide. | Maintains pH stability and optimizes respiration. |

| Oxygen Cone | Dissolved O2 saturation until 100%. | Accelerates metabolism and growth rates. |

Water Quality and the Nitrogen Cycle

Chemical management represents the most sophisticated challenge in sustainable closed-system aquaculture, with the nitrogen cycle serving as its cornerstone:

- Ammonia (NH3 / NH4): Excreted via the gills, un-ionized ammonia (NH3) is potently toxic even at concentrations as low as 0.05 mg/L.

- Nitrite (NO2): An intermediate nitrification byproduct that impairs oxygen transport in the fish’s bloodstream, potentially leading to methemoglobinemia.

- Nitrate (NO3): The terminal byproduct, which is considerably less toxic and is regulated through strategic water exchange or denitrification processes.

Predictive Modeling and Microbiological Dynamics

The current frontier of knowledge (2025–2026) focuses on the ability to anticipate chemical fluctuations before they compromise animal welfare:

- Total Ammoniacal Nitrogen (TAN) Prediction: Jiang et al. (2025) validated a mathematical model for Siberian sturgeon (Acipenser baerii) that integrates fish bioenergetics with mass balance. This tool enables the dynamic regulation of ammonia levels, effectively optimizing biofilter design.

- Nutrient Coupling (N and P): Research by An et al. (2025) reveals significant coupling between nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) cycles, mediated by microbial communities that coordinate the degradation of organic compounds in industrial systems (IRAS).

- AI in Water Management: Sun et al. (2025) demonstrate that TAN prediction accuracy improves drastically when employing GRU or LSTM neural networks combined with Pearson analysis. The study emphasizes that model selection must be calibrated based on whether the feeding regime is manual or automated.

Table 05. Recommended Optimal Parameters for RAS Operation

| Parameter | Ideal Range | Control Method |

| Dissolved Oxygen | > 90% Saturation | Oxygenation cones / Diffuser stones |

| pH | 7.0 – 8.5 | Addition of bicarbonate / caustic soda |

| Temperature | Species-dependent | Heat pumps / Chillers |

| Ammonia (TAN) | < 1.0 mg/L | Biofilter efficiency |

| Alkalinity | > 100 mg/L as CaCO3 | Chemical buffering |

Ideal Species for RAS Cultivation

The following table provides a technical synthesis of the trends and scientific advancements identified within the Recirculating Aquaculture System (RAS) literature database. The analysis reveals a diversified research framework: while the study of high-value commercial species—such as Atlantic salmon and rainbow trout—predominantly focuses on animal welfare, physiology, and stress management, research on species like tilapia and white shrimp prioritizes biofilter optimization, nitrogen cycling, and microbial community dynamics.

Table 06. Cultivated Species in Recirculating Aquaculture Systems.

| Species (Common & Scientific Name) | Scientific Advances & Themes (Based on Literature) |

| Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar) | Nitrification processes, stress management, microbiota studies, water quality optimization, animal welfare, and growth rates. |

| Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) | Water quality monitoring, ammonia toxicity, growth performance, stocking density effects, biofilter efficiency, and nitrogen cycling. |

| White Shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) | Microbial community dynamics, water quality control, stocking density, survival rates, and nitrogen removal. |

| Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) | Denitrification systems, water quality, feeding strategies, species physiology, gut microbiota, and nitrogen management. |

| Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides) | Growth performance, nutrition and feeding studies, digestive physiology, stocking density, and survival in closed systems. |

| Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio) | Growth, ammonia tolerance, survival, water quality, system microbial communities, and density management. |

| European Sea Bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) | Stress response, growth optimization, advanced nutrition, microbiota studies, and saltwater denitrification processes. |

| African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) | Aquaponics integration, phosphorus balance, circular economy in RAS, stocking density, and nutrient recycling. |

| Pike-perch (Sander lucioperca) | Animal welfare indicators, growth and survival rates, stocking density effects, feeding, and stress management. |

| Tambaqui / Gamitana (Colossoma macropomum) | Growth, nutritional requirements, histological studies, welfare under stress, and optimal densities. |

| Japanese Eel (Anguilla japonica) | Biofilter efficiency, larval growth, metamorphosis processes, nitrifying microbial communities, and nitrogen management. |

| Yellowtail Kingfish (Seriola lalandi) | Histology, associated microbiota, suspended solids management, waste handling, and physiological responses in commercial systems. |

| Sea Cucumber (Apostichopus japonicus) | Nitrogen dynamics, biofilter microbiota, feeding regimes, water quality, and microbial community correlation analysis. |

| Turbot (Scophthalmus maximus) | Metabolomics applications, ammonia stress response, physiology, nutrition, and system microbial ecology. |

| Chlorella Microalgae (Chlorella vulgaris) | Utilization of RAS effluents for biomass production (circular economy), nitrogen and phosphorus sequestration, and growth optimization. |

Collectively, Table 06 illustrates how contemporary science strives to harmonize production efficiency—driven by meticulous water quality management and nutritional oversight—with environmental sustainability through circular economy models and the valorization of byproducts.

Design and Construction: From Artisanal Models to Precision Engineering

In the development of a Recirculating Aquaculture System (RAS) project, scale is not merely a matter of size, but of technical complexity and operational stability.

Small-Scale Design (DIY and Prototyping)

Small-scale systems are ideal for academic research or subsistence production. Their fundamental architecture typically employs polyethylene tanks, gravitational sedimentation filtration, and fixed-bed biofilters with plastic media. While functional, their buffering capacity and response to biological crises remain limited.

Industrial Engineering and Scalability

An industrial-grade RAS project demands infrastructure engineered for absolute operational continuity, including:

- Critical Redundancy: Duplication of primary pumping and aeration systems.

- Energy Resilience: Emergency generators equipped with Automatic Transfer Switches (ATS).

- Operational Intelligence: Implementation of SCADA systems for real-time monitoring and autonomous control.

- Waste Management: Advanced sludge handling via geotubes or belt filters to facilitate a circular economy.

Comprehensive System Optimization

According to Dolatabadi and Ricardez-Sandoval (2025), industrial design must be approached as an integrated optimization problem, categorizing variables into three critical dimensions:

- Design Parameters: Invariant structural variables, such as Tank Retention Volume (VFT) and Bioreactor Capacity (VMBBR). These define the system’s carrying capacity and its operational flexibility against waste surges.

- Control Variables: Dynamic adjustments including feeding rate (mfeed), recirculation flow rates (Qrec), and precise oxygen injection (mO2).

- State Variables: Biological performance indicators, such as average body weight (W), population density (N), and nitrogenous compound concentrations.

System Dynamics (SD) Simulation and Modeling

Modern water quality management has transitioned toward predictive simulation. Udayakumar et al. (2025) propose System Dynamics (SD) modeling as an essential tool for anticipating the accumulation of Total Ammoniacal Nitrogen (TAN), nitrites (NO2), and nitrates (NO3).

Furthermore, Ayuso-Virgili et al. (2023) validated the use of hybrid frameworks—such as coupling Matlab with Aspen HYSYS—demonstrating this as the most effective method for simulating the thermodynamic and chemical behavior of culture tanks in high-density industrial environments.

RAS Design Framework: Sequential Phases

Phase 1: Strategic and Biological Planning

Species Selection and Market Analysis

The economic viability of an RAS is an equation where biological requirements intersect with profitability. While it is technically feasible to cultivate almost any aquatic organism, the decision must be driven by competitive pricing and operational expenditures (OPEX):

- Stage Segmentation: RAS technology is highly recommended for early life stages (fingerlings and smolts) due to accelerated growth rates and superior Feed Conversion Ratios (FCR).

- High-Value Species: For the grow-out phase, the system remains profitable with niche or luxury species (such as eel, turbot, or sturgeon) or through the large-scale production of global commodities (salmon, tilapia, or trout) that achieve economies of scale.

- Thermal Determinism: The design must guarantee optimal thermal stability for the selected species (e.g., 14°C for salmonids or 28°C for tropical species), as this parameter directly dictates metabolic efficiency and harvest cycles.

Strategic Location and Water Biosecurity

One of the primary advantages of RAS is its geographic decoupling from natural water bodies, allowing for greater operational sovereignty:

- Independence and Efficiency: Unlike conventional aquaculture, modern intensive systems require minimal makeup water, optimizing consumption to levels as low as 300 liters per kilogram of biomass produced.

- Safety Assurance: Priority is given to the use of well or deep borehole water, as it is naturally isolated from pathogens and surface contaminants. Utilizing river or seawater sources necessitates robust treatment protocols to safeguard the system’s biosecurity.

Phase 2: Engineering Design of System Components

The fundamental hydraulic cycle within a RAS follows a strict sequence: Culture Tank → Mechanical Filtration → Biological Filtration → Degassing/Aeration → Oxygenation → Return to Tank.

1. Culture Tanks

- Design: Circular or octagonal geometries are recommended to promote hydraulic patterns that facilitate self-cleaning, effectively channeling solids toward the central drain. According to Hashmi et al. (2025), tank geometry and hydrodynamics are pivotal for energy efficiency and animal welfare:

- Octagonal Tanks: These designs have been shown to enhance flow uniformity and oxygen distribution. Comparative testing revealed that octagonal configurations can achieve dissolved oxygen targets using up to 65% less pumping energy than equivalent rectangular designs.

- Diameter-to-Depth Ratio: An optimal length-to-depth ratio of 3:1 to 5:1 has been identified. Excessive depth results in underutilized volume, while shallow tanks are prone to stagnant zones.

- Avoid: Raceways are generally discouraged due to poor self-cleaning capabilities and inconsistent oxygen gradients.

2. Mechanical Filtration (Solids Removal)

- Objective: Immediate removal of feces and uneaten feed to prevent system contamination.

- Technology: The industry standard is the micro-screen drum filter, utilizing meshes ranging from 40 to 100 microns. This remains the only practical method for managing industrial-scale organic loads.

- Significance: It effectively reduces the organic burden on the biofilter and significantly improves water clarity.

3. Biological Treatment (Biofiltration)

- Function: Conversion of toxic ammonia (excreted by fish) into nitrate (less toxic) via nitrifying bacteria.

- Filter Types:

- Fixed-Bed: The plastic media remains static, doubling as a fine particle filter.

- Moving Bed (MBBR): The media is kept in constant motion through continuous aeration; it is resistant to clogging and offers high exchange rates.

- Parameters: Optimal performance is achieved within a pH range of 7.0–7.5 and temperatures between 10°C and 35°C.

Research Note (Hashmi et al., 2025): Regarding biofilter media, findings challenge the “higher surface area is always better” paradigm. Research indicates that media with a Moderate Specific Surface Area (SSA) (~750 m2/m3) yielded a better Feed Conversion Ratio (FCR) than high-SSA media (1000 m2/m3). This is attributed to the tendency of denser media to trap fine solids, which negatively impacts overall water quality.

4. Degassing and Aeration (Stripping)

- The Challenge: Fish and bacteria produce CO2, which becomes toxic if allowed to accumulate.

- Solution: Utilization of trickling filters or dedicated degassers. Water cascades over plastic media (packing), maximizing the air-water interface to strip CO2 into the atmosphere.

5. Oxygenation

- Saturation: Standard aeration only achieves 90% – 100% dissolved oxygen (DO) saturation. For high-density systems, pure oxygen injection is required to reach levels exceeding 100% (supersaturation).

- Methods:

- Oxygen Cones (Speece Cones): These mix water and oxygen under high pressure (~1.4 bar); they are highly efficient but have higher energy demands.

- Low-Head Oxygenators (LHOs): Operate at low pressure (~0.1 bar), pumping water through a mixing chamber.

6. Disinfection

- UV Radiation: Used to disrupt the DNA of bacteria and viruses. It is typically installed as submerged units. The standard dosage for bacterial control ranges from 2,000 to 10,000 µWs/cm2.

- Ozone (O3): Oxidizes organic matter and “polishes” the water, though overdosing is hazardous. Wuertz et al. (2023) established that Ozone-Produced Oxidants (OPOs) must remain below 0.05 mg/L to ensure safety for tilapia growth in brackish water.

- Emerging Technologies: Hashmi et al. (2025) highlight Cold Atmospheric Plasma (CAP) and Pulsed Electric Fields (PEF) as efficient alternatives to UV. These methods achieved bacterial reductions of 5–6 log10, operating at ambient temperatures with lower potential energy consumption.

7. Pumps and Piping

- Efficiency: Systems should be designed with a low-head approach—elevating water only once and utilizing gravity flow for the remainder of the circuit to minimize electricity costs.

- Strategic Placement: Pumps are typically positioned after mechanical filtration to prevent the fragmentation (shearing) of solids before they are extracted.

Phase 3: Waste Management and Operational Security

1. Effluent Treatment

Waste streams—comprising mechanical filter sludge and backwash water—must be treated before discharge. A buffer tank followed by belt filters can be utilized for sludge dewatering, producing nutrient-rich material suitable for fertilization. Tetreault et al. (2021) concluded that aerobic mineralization is an effective method for treating RAS effluents, significantly reducing solids while enhancing nutrient bioavailability for plants in integrated hydroponic systems. Residual water may be further processed through plant lagoons or denitrification units to mitigate nitrogen levels.

2. Safety Systems and Alarms

- Emergency Protocols: In the event of a power failure, ammonia levels escalate while dissolved oxygen (DO) depletes rapidly. A backup generator and an emergency pure oxygen injection system connected directly to the tanks are mandatory.

- Monitoring: Deployment of automated sensors for DO, temperature, and water levels is essential. Alarm systems must provide instantaneous notification to personnel, with a recommended response window of under 20 minutes.

Final Note: Physical infrastructure design must be integrated with a robust business plan, as initial CAPEX is substantial and cash flow remains negative during the initial 1–2 year growth cycle prior to the first harvest.

Economic Viability and ROI: The Investor’s Strategic Challenge

The primary barrier to the widespread adoption of Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS) lies in the delicate equilibrium between CapEx (Capital Expenditure) and OpEx (Operational Expenditure). According to Liu and Asche (2026), the financial solvency of super-intensive systems—particularly in shrimp farming—depends on a dual-pronged management strategy that mitigates both market volatility and operational vulnerabilities.

Cost Structure: CapEx vs. OpEx

Initial investment (CapEx) is substantially high; infrastructure—comprising specialized tanks, cutting-edge filtration, in-situ Pressure Swing Adsorption (PSA) oxygen generators, and climate-controlled facilities—can drive the cost per installed kilogram 3 to 5 times higher than conventional methods. Regarding operational expenditures (OpEx), the core pillars are:

- Electricity: The most critical expense, as Life-Support Systems (LSS)—including pumps and blowers—must operate 24/7.

- Nutrition: Represents 40% to 60% of production costs. However, the Feed Conversion Ratio (FCR) is significantly optimized through total environmental control.

- Human Talent: Requires highly skilled technical personnel, integrating marine biologists with systems engineering specialists.

Strategies for Profitability and Resilience (2026)

While the Return on Investment (ROI) is typically projected between 5 and 8 years, this window can be narrowed through strategic innovations:

- Circular Economy and Biotechnology: Profitability is enhanced by integrating aquaponics or the cultivation of microalgae such as Phaeodactylum tricornutum and Chlorella vulgaris, transforming nitrogenous waste into high-value commercial byproducts (Böpple et al., 2024; 2025), or as a sustainable feedstock for biofuel production.

- Hybrid Systems and Decarbonization: Ruan et al. (2026) propose the Recirculating Photovoltaic Aquaculture (AP-RAS) model, an approach that reconciles high productivity with a drastic reduction in the energy footprint through solar integration.

- Stochastic Optimization: Zhang et al. (2026) argue that design based on stochastic optimization models is superior to traditional deterministic approaches. This method builds resilient systems that account for technological and market uncertainties, ensuring economic viability in volatile scenarios.

Innovation 4.0: The Digital Future of RAS

Digitalization in modern RAS has advanced beyond basic monitoring, ushering in the era of Precision Aquaculture. Currently, environmental parameters can be managed remotely and continuously, utilizing computer vision to analyze the ethological behavior of fish in real-time. This technological integration not only optimizes feeding and disinfection strategies but also addresses the operational challenges that historically constrained the sector’s scalability (Li et al., 2023).

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Deep Learning

The implementation of AI-driven predictive models now allows for the anticipation of ammonia spikes before they reach critical thresholds, triggering preemptive feeding protocols. Furthermore, AI acts as an advanced energy manager: by dynamically optimizing oxygen supply according to the real metabolic demand of the biomass, the electricity consumption of blowers and pumps is significantly reduced.

Next-Generation Sensors and Real-Time Analytics

The transition toward full automation is supported by a network of optical sensors and high-fidelity nitrate probes. These devices eliminate reliance on manual chemical testing, providing a steady data stream that enables an immediate response to any physicochemical deviation.

Crisis Management and Biosecurity: Safeguarding System Integrity

Biosecurity in Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS) represents a critical duality: it is simultaneously the model’s greatest strength and its most sensitive vulnerability. While biological containment prevents the entry of external pathogens, high stocking densities and recirculating flows act as catalysts for propagation if a barrier fails, potentially compromising the entire biomass within extremely short timeframes.

Containment and Structural Prevention Protocols

To mitigate these operational risks, multilayered biosecurity protocols must be implemented:

- Targeted Quarantine: All initial biological material (eggs or fingerlings) must undergo a strict isolation period in independent units before integration into the main production system.

- Water Resource Sterilization: Implementation of high-impact ozonation and UV filtration systems to ensure that well or municipal water is sterile upon entry, eliminating infection vectors at the source.

- Life Support Systems (LSS): Installation of liquid oxygen tanks with passive diffusion systems, entirely independent of the electrical grid. These serve as a safeguard against critical mechanical failures or pumping collapses, ensuring fish survival until flow is restored.

Comparative Analysis: RAS vs. Traditional Systems

Table 07 presents a comprehensive comparison of the primary characteristics of Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS), marine cages, and earthen ponds.

Table 07. Comparison of RAS, Earthen Ponds, and Marine Cages.

| Characteristic | RAS | Marine Cages | Earthen Ponds |

| Water Consumption | Very low (recirculation) | High (natural flow-through) | High (evaporation/seepage) |

| Environmental Control | Total / Absolute | None / Minimal | Partial |

| Environmental Impact | Minimal (controlled waste) | High (escapes/effluent discharge) | Moderate |

| Biosecurity | Very High | Low | Moderate |

| Operating Cost (OpEx) | High (Energy-intensive) | Moderate | Low |

Conclusion

The Recirculating Aquaculture System (RAS) has established itself as a fundamental pillar of future global food security. Despite inherent technical and financial challenges, its capacity to generate animal protein predictably—paired with absolute biosecurity and minimal environmental impact—is currently unrivaled. The democratization of this technology, driven by the increasing affordability of advanced sensors and Artificial Intelligence, will enable land-based production to become the industry standard.

Nevertheless, the long-term consolidation of RAS depends on overcoming critical hurdles. As noted by Brown et al. (2025), viability requires optimizing resource consumption, ensuring technical stability in marine environments, and perfecting saline effluent management. In this regard, the transition toward simplified, low-OpEx designs powered by renewable energy is imperative to reduce the carbon footprint and facilitate mass adoption (Ahmed & Turchini, 2021). Ultimately, the success of RAS will lie in its ability to reconcile maximum productivity with climate resilience.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the fundamental difference between RAS and traditional aquaculture?

Unlike open-net pen systems or earthen ponds, RAS operates as a land-based, closed-loop ecosystem. Its competitive advantage stems from the ability to recirculate up to 99% of the water, enabling absolute control over critical parameters such as dissolved oxygen, temperature, and biosecurity, independent of external climatic conditions.

Which species are the most profitable for cultivation in these systems as of 2026?

Economic feasibility typically prioritizes high-market-value species or those in critical developmental stages; currently, Atlantic Salmon (post-smolts), trout, sturgeon, and white shrimp dominate the industry. RAS technology is particularly advantageous for fry and juveniles, as it maximizes survival rates and optimizes growth performance before transfer or final harvest.

How does Artificial Intelligence (AI) impact the management of a modern RAS?

AI has transitioned from a theoretical promise to a core operational component. By leveraging Deep Learning algorithms and computer vision, modern systems are capable of:

– Predicting ammonia spikes before they reach critical thresholds, allowing for preemptive intervention.

– Optimizing feeding regimes through the real-time analysis of fish ethological behavior, effectively mitigating feed waste.

– Managing energy consumption predictively, facilitating the seamless integration of renewable energy sources and grid load balancing.

What are the primary economic challenges for an investor in a Recirculating Aquaculture System?

The most significant barrier remains the substantial CapEx (initial capital investment in infrastructure and technology). However, OpEx (operational expenditures) are being substantially reduced through enhanced energy efficiency and strategic siting near major consumption hubs. The current industry standard involves utilizing stochastic optimization frameworks, which enable the design of systems resilient to market volatility and fluctuating energy prices.

Is it possible to eliminate the “earthy” taste (off-flavor) in fish raised in RAS?

Yes. The implementation of advanced technologies, such as Field Asymmetric Ion Mobility Spectrometry (FAIMS), now enables the detection of compounds like geosmin and MIB with unprecedented precision. Furthermore, modern depuration protocols and Cold Atmospheric Plasma (CAP) disinfection ensure that the fillet reaches the consumer with an impeccable sensory profile. These innovations effectively eliminate the need for extended fasting periods, which historically resulted in significant biomass loss.

How is biosecurity ensured in such a high-density environment?

The strategy is built upon a defense-in-depth framework:

– Isolation: Implementation of stringent quarantine protocols for all incoming biological stock.

– Sterilization: Utilization of high-intensity UV irradiation and ozonation for both influent and recirculating water.

– Passive Redundancy: Deployment of Liquid Oxygen (LOX) systems that operate independently of the electrical grid, safeguarding the biomass against mechanical or power failures.

Is a home-scale recirculating aquaculture system profitable?

While viable for subsistence or R&D purposes, commercial profitability is typically achieved only at scales that allow for the dilution of fixed overheads, specifically energy and monitoring costs. The commercial viability threshold generally commences at an annual production of 10 – 20 metric tons, depending on the species’ market value and specific growth requirements.

References

Ahmed, N., & Turchini, G. M. (2021). Recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS): Environmental solution and climate change adaptation. Journal of Cleaner Production, 297, 126604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126604

An, S., Li, J., Du, J., Feng, L., Zhang, L., Zhang, X., Zhuang, Z., Zhao, Z., & Yang, G. (2025). Coupled nitrogen and phosphorus cycles mediated by coordinated variations of functional microbes in industrial recirculating aquaculture system. Water Research, 280, 123726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2025.123726

Ayuso-Virgili, G., Jafari, L., Lande-Sudall, D., & Lümmen, N. (2023). Linear modelling of the mass balance and energy demand for a recirculating aquaculture system. Aquacultural Engineering, 101, 102330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaeng.2023.102330

Böpple, H., Kymmell, N. L., Slegers, P. M., Breuhaus, P., & Kleinegris, D. M. (2024). Water treatment of recirculating aquaculture system (RAS) effluent water through microalgal biofilms. Algal Research, 84, 103798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.algal.2024.103798

Böpple, H., Slegers, P. M., Breuhaus, P., & Kleinegris, D. M. (2025). Comparing continuous and perfusion cultivation of microalgae on recirculating aquaculture system effluent water. Bioresource Technology, 418, 131881. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2024.131881

Bregnballe, J. (2015). Recirculation aquaculture. FAO and Eurofish International Organisation: Copenhagen, Denmark. 100 p.

Brown, A. R., Wilson, R. W., & Tyler, C. R. (2025). Assessing the Benefits and Challenges of Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS) for Atlantic Salmon Production. Reviews in Fisheries Science & Aquaculture, 33(3), 380–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/23308249.2024.2433581

Deng, Y., Verdegem, M. C., Eding, E., & Kokou, F. (2022). Effect of rearing systems and dietary probiotic supplementation on the growth and gut microbiota of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) larvae. Aquaculture, 546, 737297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2021.737297

Dolatabadi, S., & Ricardez-Sandoval, L. (2025). Integration of process design and control of a pilot-scale recirculating aquaculture system. Aquacultural Engineering, 111, 102580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaeng.2025.102580

Good, C., Redman, N., Murray, M., Straus, D. L., & Welch, T. J. (2022). Bactericidal activity of peracetic acid to selected fish pathogens in recirculation aquaculture system water. Aquaculture Research, 00, 1– 6. https://doi.org/10.1111/are.16031

Hashmi, Z., Metali, F., Amin, M., Abu Bakar, M. S., Wibisono, Y., Nugroho, W. A., & Bilad, M. R. (2025). Recirculating aquaculture systems: Advances, impacts, and integrated pathways for sustainable growth. Bioresource Technology Reports, 32, 102340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biteb.2025.102340

Jiang, L., Jia, M., Guo, B., Li, D., & Chen, T. (2025). Mathematical modelling of ammonia nitrogen dynamics in a recirculating aquaculture system. Aquacultural Engineering, 111, 102594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaeng.2025.102594

Krishna, D., Petersen, P. E., Dahl, M. M., Egholm, I., Jørgensen, L. V. G., & Christiansen, D. H. (2026). Environmental DNA/RNA for non-invasive early detection and monitoring of pathogen dynamics in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS). Aquaculture, 611, 743060. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2025.743060

Li, H., Cui, Z., Cui, H., Bai, Y., Yin, Z., & Qu, K. (2023). A review of influencing factors on a recirculating aquaculture system: Environmental conditions, feeding strategies, and disinfection methods. Journal of the World Aquaculture Society, 54(3), 566-602. https://doi.org/10.1111/jwas.12976

Liu, L., & Asche, F. (2026). Risk analysis for shrimp in a recirculating aquaculture system. Aquaculture, 614, 743467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2025.743467

Liu, C., Yang, X., Liu, B., Zhao, Z., Ma, P., Fu, T., Hu, W., Gao, X., & Zhou, C. (2026). Accurate and real-time fish feeding intensity scoring using channel convolution GLU and SMFA attention fusion in recirculating aquaculture system. Aquaculture, 612, 743180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2025.743180

Malone, R. (2013). Recirculating Aquaculture Tank Production Systems: A Review of Current Design Practice (SRAC Publication No. 453). Southern Regional Aquaculture Center. 12 p.

Ranjan, R., Kothawade, G. S., Davidson, J., & Khot, L. R. (2026). Feasibility study of Field Asymmetric Ion Mobility Spectrometry (FAIMS) for rapid off-flavor detection in recirculating aquaculture system cultured Atlantic salmon. Aquacultural Engineering, 112, 102622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaeng.2025.102622

Ruan, Z., Xu, J., Yao, H., Yin, P., Zhao, J., Chen, X., Guo, Q., Ou, H., Zeng, W., & Huang, W. (2026). Innovative aquaculture-photovoltaic recirculating aquaculture system: Design, performance and microbial ecological mechanisms. Aquaculture, 613, 743337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2025.743337

SUN Xueqian, LI Li, DONG Shuanglin, TIAN Xiangli, ZHANG Shengkun. Ammonia nitrogen prediction model for recirculating aquaculture system based on different feeding strategies[J]. Journal of fisheries of china, 2025, 49(1): 019611. DOI: 10.11964/jfc.20220613532

Tetreault, J., Fogle, R., & Guerdat, T. (2021). Towards a Capture and Reuse Model for Aquaculture Effluent as a Hydroponic Nutrient Solution Using Aerobic Microbial Reactors. Horticulturae, 7(10), 334. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae7100334

Udayakumar, R., Kadirov, I., Radjabova, D., Fallah, M. H., Tursunov, M., & Masalieva, O. (2025). A System Dynamics Model for Water Quality Management in Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (Ras). Natural and Engineering Sciences, 10(2), 434-446.

Wang, H., Xu, H., Lu, C., Chen, X., Zhang, Z., & Zhai, Z. (2026). FeedingMonitor: An improved TNT-based method for evaluating the fish feeding intensity in the recirculating aquaculture system. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 240, 111233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2025.111233

Wuertz, S., Schulz, C., Klatt, S., Kleiner, W., & Schroeder, J. P. (2023). Adverse effects of ozonation on the animal welfare of tilapia Oreochromis niloticus in recirculation aquaculture. Aquaculture Reports, 32, 101737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aqrep.2023.101737

Yang, H., Wang, X., Shi, Y., Wang, J., Jia, B., Zhou, C., & Ye, H. (2025). Research on a precise feeding method for fry in recirculating aquaculture systems. Aquaculture Reports, 45, 103083. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aqrep.2025.103083

Zhang, R., Chen, T., Wang, Y., & Short, M. (2026). Design of integrated renewable energy and recirculating aquaculture systems under uncertainty: A two-stage stochastic optimisation approach. Applied Energy, 406, 127290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2025.127290

Editor at the digital magazine AquaHoy. He holds a degree in Aquaculture Biology from the National University of Santa (UNS) and a Master’s degree in Science and Innovation Management from the Polytechnic University of Valencia, with postgraduate diplomas in Business Innovation and Innovation Management. He possesses extensive experience in the aquaculture and fisheries sector, having led the Fisheries Innovation Unit of the National Program for Innovation in Fisheries and Aquaculture (PNIPA). He has served as a senior consultant in technology watch, an innovation project formulator and advisor, and a lecturer at UNS. He is a member of the Peruvian College of Biologists and was recognized by the World Aquaculture Society (WAS) in 2016 for his contribution to aquaculture.