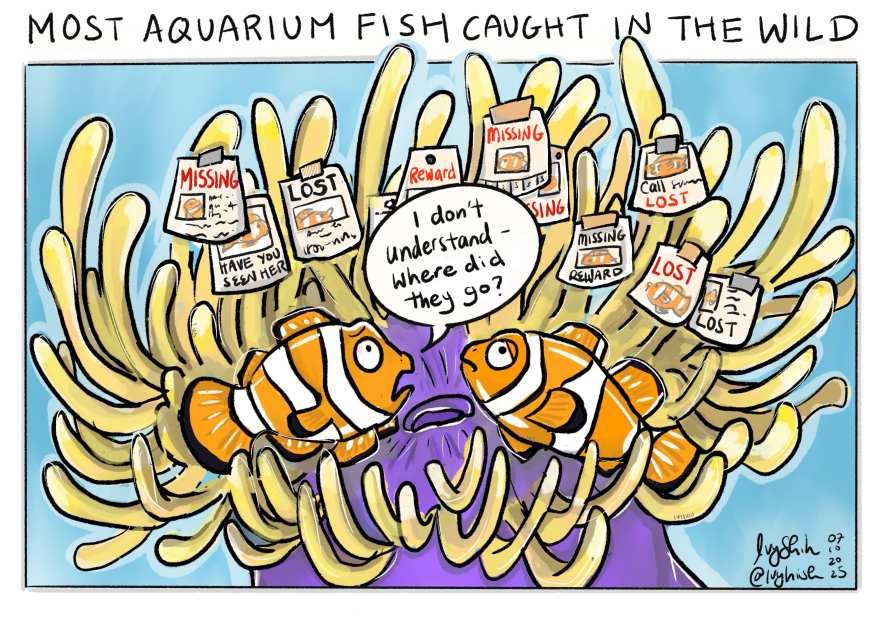

The lucrative and non-transparent trade of marine ornamental fish in the United States is primarily supplied by specimens collected from coral reefs, including threatened species. A new investigation analyzes the online market, highlighting both the conservation risks and the potential for aquaculture to offer a more sustainable alternative.

The marine aquarium hobby is a multi-billion dollar global industry, with the United States as the main importer, absorbing nearly two-thirds of the world’s supply. Much of this business has moved into the digital realm, where the ease of purchase conceals a complex supply chain with significant ecological implications.

A recent study published in Conservation Biology by researchers from Princeton University, the University of Sydney, Nanyang Technological University, Roger Williams University, and the University of Massachusetts Boston has shed light on this market. It analyzed the offerings of the four main e-commerce platforms for marine fish in the U.S. between July 2021 and November 2024. The findings are stark: the reliance on wild-caught fish is overwhelming, and the information available to assess their sustainability is, in many cases, insufficient.

Key findings

- 89.2% of the 734 marine fish species sold on the main U.S. online platforms are sourced exclusively from the wild.

- 45 species of conservation concern (threatened or with declining populations) were identified for sale, 38 of which are obtained solely from the wild.

- 100 of the species traded were not registered as part of the aquarium trade in reference databases like FishBase or the IUCN, indicating a lack of tracking.

- For species available from both wild and cultured sources, aquacultured specimens were, on average, 28.1% cheaper than their wild counterparts.

Where do our aquarium fish come from?

To understand the market’s scale, researchers collected data on 734 unique species from 13 of the most popular fish families in the aquarium hobby. The analysis revealed that the source of these animals is predominantly extractive:

- 89.2% of species (655 total) are obtained exclusively from the wild.

- Only 2.9% (21 species) come solely from aquaculture.

- 6.8% (50 species) are available from both wild capture and aquaculture.

The research highlights that many of the most traded species, such as wrasses (Labridae), clownfish and other damselfish (Pomacentridae), and gobies (Gobiidae), are collected from tropical reefs, often in the Indo-Pacific region. These regions have long been hotspots for the marine ornamental trade, where unsustainable fishing practices, including the use of cyanide, have been documented. At the same time, they also host sustainable fisheries that serve as models for responsible trade. For local communities in these areas, collecting ornamental fish can be an important source of income.

Threatened species in the shopping cart

Beyond the scale of the trade, one of the greatest concerns is the impact on vulnerable populations. Alarmingly, the study identified that 45 of the species for sale are of conservation concern, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Of these, 20 are classified as threatened, and an additional 25 exhibit declining population trends.

Worryingly, 38 of these 45 vulnerable species are sourced exclusively from wild capture. This means hobbyist demand could be directly contributing to the decline of species already facing a high risk of extinction.

Furthermore, the study uncovered significant information gaps. One hundred of the traded species were not listed as part of the aquarium trade in the IUCN or FishBase databases. Added to this are 34 species classified as “Data Deficient” and 463 with unknown population trends, which greatly complicates the management and regulation of the trade.

The price of wild vs. cultured

The study also explored the factors influencing fish prices. It was found that the cheapest specimens tend to be those that are smaller, live in shallower waters, and form schools—characteristics that make them easier to capture.

Stay Always Informed

Join our communities to instantly receive the most important news, reports, and analysis from the aquaculture industry.

A finding that should be a catalyst for change in the market is that aquacultured fish are cheaper. When comparing the prices of the 50 species offered from both wild and aquacultured sources, captive-bred specimens were significantly more affordable. On average, an aquacultured fish cost 28.1% less than its wild-caught counterpart.

“The fact that aquacultured fish are often cheaper than their wild-caught counterparts suggests that sustainable alternatives are not only possible but also profitable,” stated Dr. Lin, the study’s lead researcher. However, the vast majority of fish in the U.S. market remain wild-caught. “Consumer preferences, technical and biological barriers to breeding, and unclear supply chains continue to fuel the demand for wild-caught fish,” he added.

Aquaculture and sustainable management as conservation tools

The study’s authors note that a shift toward captive propagation could alleviate pressure on wild populations and reduce ecological damage. However, Dr. Lin emphasized the importance of a balanced approach that protects biodiversity and reef ecosystems while supporting the livelihoods of coastal communities in the source regions.

“Investing in aquaculture, supporting well-managed wild fisheries, implementing credible eco-certification schemes, and reducing demand for unsustainably caught fish could help steer the industry toward a more sustainable path,” Dr. Lin explained.

This comprehensive vision is crucial, as a complete shift to aquaculture in importing countries could harm the fishing communities that depend on this trade. Therefore, promoting sustainable wild fisheries is a complementary and viable option.

Toward a more transparent and sustainable trade

The opacity of the industry is a fundamental obstacle. “We urgently need greater traceability and regulatory oversight to ensure that aquarium fish are sourced responsibly,” declared Dr. Lin. “Consumers have no reliable way of knowing if the fish they purchase were sustainably caught.”

Although it was not part of this study, Dr. Lin also noted that the aquarium fish market in Australia faces similar issues. “Australia is among the top 20 global importers of live ornamental fish. That isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but when the global trade is so opaque, we are left guessing where each fish came from and how it was caught.”

To drive change, public awareness is key. “Public awareness of the ecological impacts of the aquarium trade is also critical for driving better consumer decisions and meaningful policy reform,” he affirmed.

“We hope our findings motivate lawmakers, industry stakeholders, and consumers to work together to safeguard vulnerable reef species, foster sustainable trade practices, and support the coastal communities whose livelihoods depend on this industry,” Dr. Lin concluded.

Contact

Bing Lin and David S. Wilcove

School of Public and International Affairs, Princeton University

Princeton, NJ, USA.

Email: thebinglin@gmail.com and dwilcove@princeton.edu

Reference (open access)

Lin, B., Zeng, Y., To, B., Holmberg, R. J., Rhyne, A. L., Tlusty, M., & Wilcove, D. S. Extent of threats to marine fish from the online aquarium trade in the United States. Conservation Biology, e70155. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.70155

Editor at the digital magazine AquaHoy. He holds a degree in Aquaculture Biology from the National University of Santa (UNS) and a Master’s degree in Science and Innovation Management from the Polytechnic University of Valencia, with postgraduate diplomas in Business Innovation and Innovation Management. He possesses extensive experience in the aquaculture and fisheries sector, having led the Fisheries Innovation Unit of the National Program for Innovation in Fisheries and Aquaculture (PNIPA). He has served as a senior consultant in technology watch, an innovation project formulator and advisor, and a lecturer at UNS. He is a member of the Peruvian College of Biologists and was recognized by the World Aquaculture Society (WAS) in 2016 for his contribution to aquaculture.