Over the past decade, microalgal or algal biofuels—known as third-generation biofuels—were hailed as a renewable energy paradigm due to their rapid growth, high lipid content, and lack of competition for agricultural land (Wang et al., 2026). While they promised to mitigate reliance on fossil fuels, industrial implementation has proven complex.

Leading corporations, such as ExxonMobil, have recalibrated their expectations following significant investments. This has driven research evolution from conventional extraction toward advanced processes like Hydrothermal Liquefaction (HTL) and genetic engineering. Simultaneously, cultivating microalgae in wastewater has emerged as a key strategy to reduce costs and achieve economic viability.

- 1 Key Conclusions

- 2 What are Algal Biofuel?

- 3 Biofuel Market Projections and Regulatory Framework

- 4 Scientific Trends in Microalgal Biofuel Production

- 5 Technological Trends in Algal Biofuel Production

- 6 Technological Trends in Microalgal Biofuel Production

- 7 Algal Biofuel Production

- 8 Benefits of Third-Generation Biofuels

- 9 Challenges and Technical Limitations in Algal Biofuel Implementation

- 10 Chemistry of Algal Biofuels

- 11 Uses and Applications of Algal Biofuels

- 12 Future of Third-Generation Biofuels

- 13 Conclusion

-

14

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- 14.1 How do algal biofuels (third generation) differ from previous generations?

- 14.2 What are the main technological pathways for producing these fuels?

- 14.3 Why is integrating biofuel production with wastewater crucial?

- 14.4 What role does genetic engineering play in the future of this industry?

- 14.5 Are they economically competitive with fossil fuels?

- 14.6 What trends do patents reveal about innovation in the sector?

- 15 References

- 16 Entradas relacionadas:

Key Conclusions

- Circular Economy Integration: The industry has evolved from solely selling fuel to offering Circular Economy solutions. Current profitability lies in charging for wastewater treatment and industrial CO₂ capture, turning biofuel into a valuable byproduct of a global sanitation system.

- Synthetic Biology & Bio-foundries: Thanks to tools like CRISPR, reliance on wild algae is decreasing. Today, cellular “bio-foundries” are optimized to continuously secrete lipids (known as “milking” technology), avoiding crop destruction and drastically reducing costs.

- Multi-product Strategy: The “fuel-only” model is obsolete. The winning trend is multi-production: extracting high-value compounds (like Omega-3s and antioxidants) for pharmaceutical markets first, utilizing the residual biomass for energy generation.

- Carbon Avoidance over Oil Yield: Success is no longer measured merely by oil volume, but by carbon avoidance. Technology is now evaluated via Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) to ensure a positive energy balance and genuine greenhouse gas reduction.

What are Algal Biofuel?

Classified as third-generation biofuels, these are derived from various species (microalgae and macroalgae) cultivated in diverse aquatic environments using closed systems (photobioreactors), open systems (ponds), or hybrid configurations. Through photosynthesis, these organisms transform solar energy into biomass, which can be processed into a wide range of energy carriers, such as biodiesel, bioethanol, biohydrogen, biobutanol, and biogas.

Conceptually, Sarwan et al. (2024) define biofuels as “energy sources derived from living cells through the degradation of lignocellulosic or cellulosic biomass to produce ethanol and diesel.” Furthermore, the authors note that fuels generated with microbial assistance via fermentation processes are specifically termed bioethanol and biodiesel.

Algae-Based Biofuels Classification

The term “algae-based biofuel” refers to any energy obtained from processing algal biomass. These products are classified into liquid fuels—such as biobutanol, biodiesel, and bioethanol—and gaseous fuels, a category that includes biogas and biohydrogen (Mahmood et al., 2023).

The capacity of microalgae to maintain accelerated proliferation rates via photosynthesis, while assimilating carbon dioxide and nutrients, positions them as ideal feedstocks (raw materials) for this purpose (Neeti et al., 2023). Additionally, their energy conversion efficiency—superior to conventional biomass sources—consolidates their appeal as a viable alternative for biofuel production.

Biofuel Market Projections and Regulatory Framework

Global Growth Trends

The OECD/FAO projections (2025) for the coming decade (2025-2034) indicate continued growth in the biofuel sector, albeit with a significant deceleration compared to the previous decade. While consumption experienced a 3.3% annual growth rate over the last ten years, this figure is estimated to drop to 0.9% annually for the 2025-2034 period. In absolute terms, global biodiesel production is forecast to reach 80.9 billion liters by 2034.

Commercial Barriers and Technical Viability

Despite their high biological potential, Neokosmidis (2025) underscores that algal biofuels remain largely in the experimental stage. High cultivation and harvesting costs have stalled large-scale commercialization, prompting capital withdrawal by numerous investors. The sector’s future viability depends on implementing Multi-product Biorefinery models, capable of commercializing high value-added co-products to offset fuel costs.

Technologically, Neokosmidis (2025) highlights the relevance of microalgae for two main pathways: biodiesel production via lipid extraction and transesterification, and the generation of renewable diesel and Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) through direct oil hydrotreating.

Stay Always Informed

Join our communities to instantly receive the most important news, reports, and analysis from the aquaculture industry.

However, the OECD/FAO (2025) warns that, despite growing interest, the algal market share will remain negligible in baseline projections until 2034 due to persistent technological barriers and high capital expenditure (CAPEX) requirements.

Regulatory Context (European Union)

In the regulatory realm, Flach et al. (2025) report that algae have been integrated into Part A of Annex IX of the European Union’s Renewable Energy Directive (REDII). This classification categorizes algal biofuels as “advanced,” allowing them to count towards the EU’s binding targets (a 1% share in 2025 and 5.5% in 2030). Nevertheless, the study reveals a discrepancy between policy and practice: the current European industry continues to prioritize cheaper and more mature feedstocks.

Current Production and Geographic Distribution

Finally, Neokosmidis (2025) reports that the global scale of microalgae production remains modest, standing at approximately 56.5 kilotons (kt). China consolidates its position as the undisputed leader, accounting for 97% of the global volume.

It is crucial to note, however, that only a marginal fraction of this volume is intended for energy purposes; the vast majority of biomass produced is currently directed towards the dietary supplement and cosmetic markets, where profit margins justify production costs.

Scientific Trends in Microalgal Biofuel Production

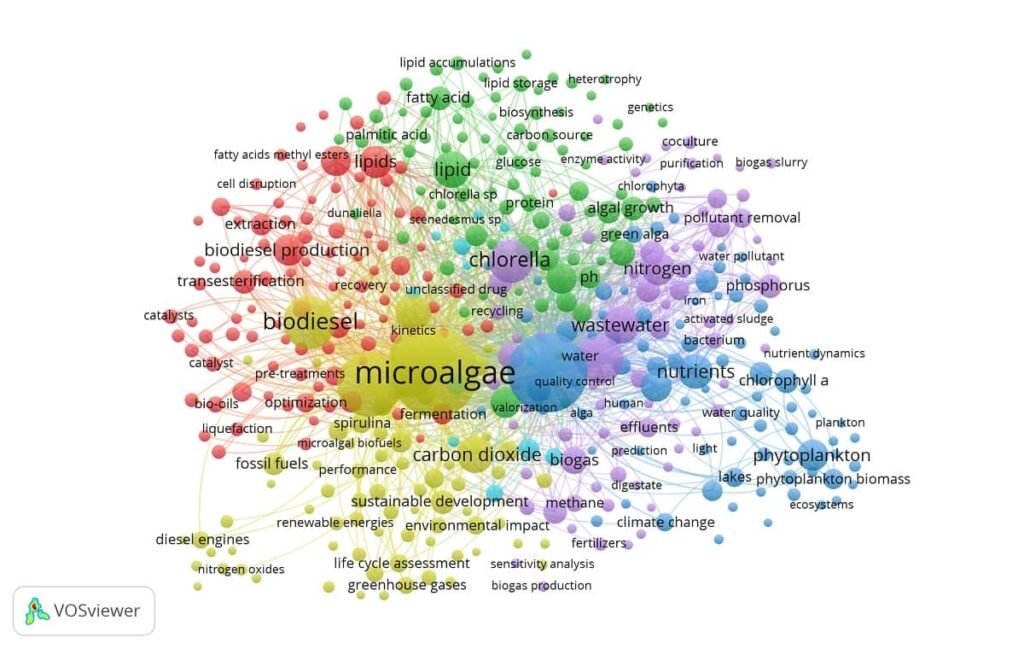

To identify emerging technological trends in algal biofuel production, a bibliographic search was conducted in the Scopus database, and the data were processed using VOSviewer software. This procedure allowed for the definition of the main thematic clusters and the visualization of the evolution of research areas.

Thematic Clusters

The generated network analysis reveals that research on microalgae and biofuels is not a monolithic field; rather, it is structured into five interconnected thematic clusters (see Figure 2), representing the distinct disciplines required for the consolidation of this technology.

Topological analysis indicates that the term Microalgae acts as the central node (hub). However, the most significant relationship for the technology’s future viability lies in the high link strength detected between the Red Cluster (Processes) and the Purple Cluster (Wastewater).

This finding confirms that the dominant trend in scientific literature is process integration: while biodiesel production is technically feasible (Red Cluster), its economic sustainability and ecological justification (Yellow Cluster) are intrinsically dependent on its coupling with wastewater treatment (Purple Cluster).

The following section details the analytical interpretation of each identified thematic cluster:

Red Cluster: Process Engineering and Chemical Conversion (Downstream Processing)

This cluster, dominated by terms such as biodiesel, transesterification, and extraction, represents the chemical engineering component within the network. The grouping suggests that a significant volume of literature has focused on resolving challenges in the final stage or downstream processing: the efficient extraction of intracellular lipids and catalytic optimization to obtain Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (FAMEs)—i.e., biodiesel. The prevalence of the term optimization indicates that this area has reached technical maturity, where the current focus lies on the incremental improvement of yields.

Green Cluster: Fundamental Biology and Strain Selection (Upstream)

Centered on biology, this group highlights the predominant model species in the industry: the genera Chlorella and Scenedesmus. The co-occurrence of terms such as biosynthesis, proteins, and fatty acids reveals that biological research prioritizes metabolic manipulation to induce the accumulation of energy-relevant metabolites. This cluster constitutes the fundamental basis (upstream), demonstrating that selecting the appropriate strain remains the critical first step for the success of any bioprocess.

Purple/Dark Blue Cluster: The Water-Energy Nexus (Circular Economy)

This strategic cluster links economic viability with environmental sanitation. The strong association between wastewater, nutrients (N, P), and pollutant removal evidences a paradigm shift: microalgae cultivation is no longer viewed solely as a means of energy production but has consolidated as a bioremediation tool.

In this regard, Loni et al. (2026) highlight that integrating microalgae cultivation with wastewater derived from biomethanization (ADW) represents a sustainable and economically viable approach for nutrient recovery and biofuel generation. Consistently, De Freitas et al. (2023) point out that treatment plants can be transformed into biorefineries capable of depurating effluents while simultaneously acting as photosynthetic conversion units, transforming waste and CO₂ into high-value chemicals. This dual-purpose approach is key to reducing operating expenses (OPEX) by eliminating dependence on synthetic fertilizers and freshwater.

Yellow Cluster: Global Sustainability and Climate Policy

This group contextualizes the technology within the macro-environmental scope. Terms such as Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), CO₂, and Sustainable development suggest that the validation of algal biofuels is intrinsically dependent on their carbon balance. Research in this cluster transcends technical viability (“how to do it”) to focus on impact assessment (“what are the effects”), justifying the technology as a vital strategy for decarbonization and greenhouse gas mitigation.

Light Blue Cluster: Ecology and Natural Systems

Finally, the presence of terms such as phytoplankton, lakes, and ecosystems signals a research line based on fundamental ecology. This suggests that applied knowledge regarding photobioreactors is informed by an understanding of algal dynamics in natural environments, as well as studies on the ecological impact derived from algae proliferation.

Thematic Research Trends

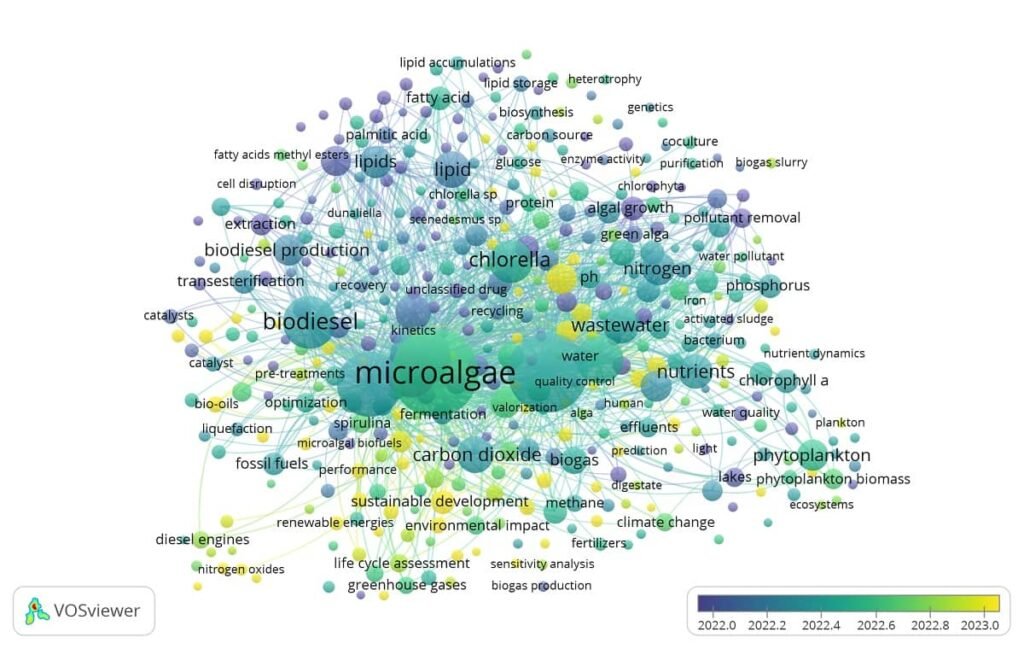

The temporal overlay visualization presented in Figure 03 reveals a dynamic shift in the research front over a brief timeframe, underscoring the accelerated maturation of this field of study.

Bibliometric results substantiate a significant paradigm shift in recent literature: the research focus has evolved from the technical optimization of unit processes—such as transesterification and lipid extraction—towards a holistic vision grounded in the circular economy. Within this new landscape, Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and greenhouse gas mitigation have consolidated their positions as the primary drivers of innovation.

The temporal evolution of terminology allows for the delineation of three distinct development phases:

Phase of Technical Consolidation (Blue/Purple Nodes)

The predominant terms in the first half of the analyzed period—such as lipids, extraction, and transesterification—constitute the consolidated technical foundation of the discipline. The prevalence of these concepts in the initial period indicates that the fundamental challenges of reaction engineering, specifically the efficiency in converting lipids to FAMEs (biodiesel), have been widely addressed. This stage was characterized by a “product-oriented” vision, focused almost exclusively on maximizing fuel yield.

Phase of Transition and Integration (Green Nodes)

As research advanced towards the intermediate stage, key terms such as wastewater, biogas, and nitrogen emerged. This transition marks the shift from laboratory optimization towards process integration. The scientific community began to prioritize the use of genera like Chlorella not only for their lipid content but for their robustness to proliferate in effluents, validating the hypothesis that economic viability depends on harnessing low-cost nutrients (waste).

In this regard, Pires et al. (2024) underscore the opportunity to valorize industrial liquid effluents (such as those from fertilizer factories) and CO₂-rich gaseous emissions (cement industry) for microalgae cultivation.

Current Knowledge Frontier (Yellow Nodes)

The most recent literature (late 2022–2023) reveals a substantial paradigm shift towards systemic sustainability. The preeminence of terms such as Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), greenhouse gases, and circular economy demonstrates that current interest transcends “how to produce” biofuel, focusing instead on validating its positive environmental impact.

Additionally, the appearance of the term fertilizers at this stage is crucial, as it suggests that research is transitioning towards the Biorefinery model, where post-extraction residual biomass is valorized as biofertilizer. Ruales et al. (2025) maintain that this approach allows for the utilization of the entire biomass, minimizing waste and maximizing economic and energetic value. In this sense, integrating the production of biostimulants and biogas from Scenedesmus sp. is consolidating as an effective strategy for resource recovery within a circular economy scheme.

Technological Trends in Algal Biofuel Production

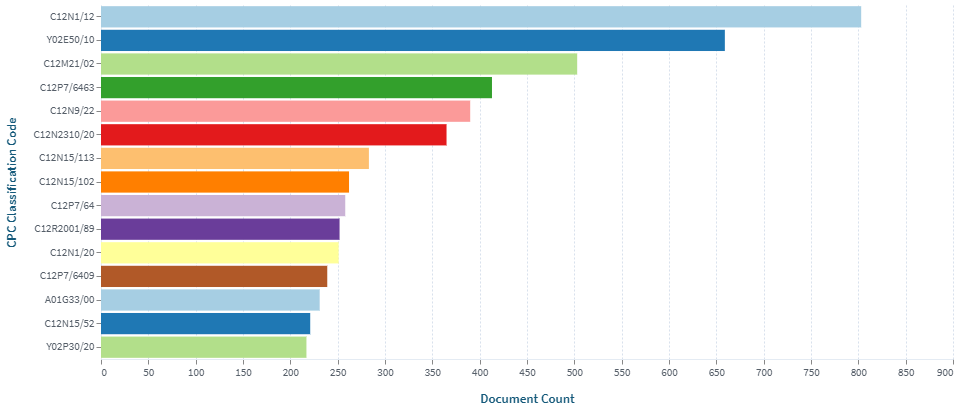

Technological Distribution of Patents

The analysis of the Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC) applied to the set of 1,678 patent families elucidates the sector’s technological hierarchy (Figure 04), revealing priorities that differ from conventional industrial perception.

At the apex of this structure, with a preponderance of 680 documents, lies code C12N 1/12, referring to unicellular microorganisms and their culture media. This prevalence indicates that the primary protected intellectual asset is neither the machinery nor the final fuel, but the biological design and the robustness of the strain itself. This finding confirms that, for the industry, the critical “bottleneck” remains cellular productivity, prioritizing the acquisition of a stable biological feedstock prior to scaling up manufacturing processes.

Secondly, code C12M 21/02 (461 documents) stands out, encompassing cultivation apparatus, specifically photobioreactors. The significant coexistence of strain development and reactor design suggests that the industry understands that advanced biology requires equally sophisticated hardware to operate efficiently. Complementarily, inventions grouped under code C12P 7/6463 (296 documents) focus on the technical stage of lipid and fatty acid extraction; a phase that, while essential, appears numerically subordinate to cultivation and reactor design.

Meanwhile, code Y02E 50/10 specifically categorizes technologies for climate change mitigation through biofuel production. Its high frequency functions as a strategic indicator validating investment: it confirms that a significant proportion of inventions in this field are explicitly designed and justified under the imperative of global decarbonization, aligning intellectual property with green financing incentives and international environmental regulations.

Analysis of Patent Applicants

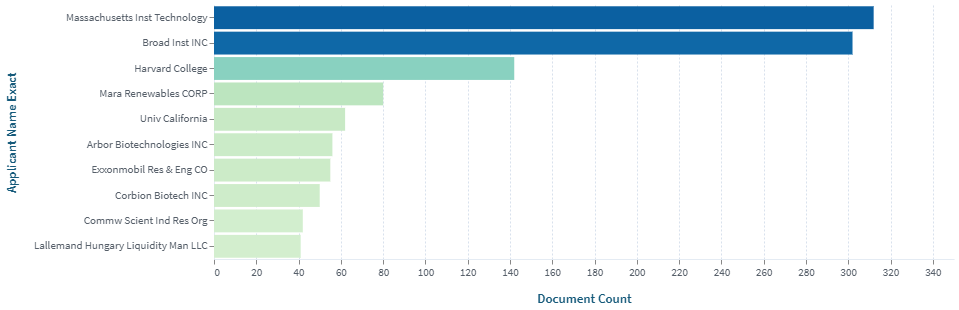

The analysis of top applicants reveals a highly polarized innovation hierarchy, spearheaded by a specific geographic and academic node. Data identify the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and the Broad Institute as the undisputed sector leaders (Figure 05), concentrating the highest number of unique patent families (98 and 91, respectively). This concentration demonstrates that the current engine of innovation in microalgal biofuels resides not in the traditional energy industry, but in centers of excellence for biotechnology and gene editing located in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

A significant structural gap is observed between these two leaders and the rest of the ecosystem. MIT and the Broad Institute hold dominance in frontier technologies, such as CRISPR-Cas9. At a secondary tier are Harvard College (26 families) and the University of California (26 families), institutions maintaining a sustained pace of innovation, albeit without reaching the disruptive volume of the leaders.

Meanwhile, the private sector exhibits a relevant dual dynamic. On one hand, ExxonMobil Research & Engineering ranks third globally (36 families), confirming the fossil fuel sector’s strategic interest in validating this technology at an industrial scale.

On the other hand, specialized emerging players such as Mara Renewables (14 families) and Arbor Biotechnologies (13 families) are rising; while their patent volume is lower, their presence indicates a viable commercial niche focused on high value-added products, contrasting with the volume-based strategy of large corporations.

Finally, the participation of public bodies like Australia’s CSIRO (12 families) and European companies like DSM IP Assets (26 families) demonstrates that, while leadership is American and academic, the technological vanguard is global and diverse. This structure suggests that while fundamental research is defined in Boston (MIT/Broad/Harvard), technological application is diversifying toward global industrial players seeking to transform these biological inventions into tangible market solutions.

Technological Trends in Microalgal Biofuel Production

Based on a review of scientific literature and patent analysis, three macro-trends have been identified that define the state-of-the-art and future projections for the use of microalgae for energy purposes. A detailed analysis of these trajectories is presented below.

From Natural Selection to Genetic Design

Comparative analysis reveals a fundamental paradigm shift. While literature from the past decade focused on bioprospecting and the screening of wild strains, recent patent activity—led by institutions such as the Broad Institute (CPC code C12N 9/22)—indicates a decisive transition toward Synthetic Biology.

This disruption implies that the economic viability of third-generation biofuels no longer depends on the serendipitous discovery of new species, but on the capacity to rewrite the genome of model organisms (Chlorella, Nannochloropsis) using gene-editing tools like CRISPR-Cas9.

The primary objectives of this metabolic engineering are:

- Carbon Flux Redirection: Maximizing the pathway toward lipogenesis at the expense of carbohydrate production.

- Photosynthetic Optimization: Reducing the size of light-harvesting antennae to minimize self-shading in high-density photobioreactors.

- Facilitation of Extraction: Inducing lipid secretion mechanisms to enable non-destructive recovery processes.

Decarbonization and Ecosystem Services as a New Business Model

Convergence of Evidence: Regulatory and Environmental Validation

Cross-referencing data between scientific literature and patent registries evidences that sustainability has ceased to be a mere “green label” to become the core of financial viability.

- From Technology: The preeminence of CPC code Y02E 50/10 (Technologies for mitigation of climate change in biofuel production) ranking third indicates that Intellectual Property is structuring itself to fit international regulatory frameworks (such as the European Green Deal or carbon markets). Companies do not patent “fuel”; they patent “carbon capture mechanisms” that happen to result in fuel, thus ensuring eligibility for subsidies and tax credits.

- From Science: The recent dominance of terms like Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Global Warming Potential (GWP) in “Hot Topics” indicates that the academic community has accepted a harsh reality: the Net Energy Ratio (NER) is more critical than lipid content. Research no longer seeks merely “how much oil is produced,” but “how much CO₂ is avoided” per megajoule generated.

The Inversion of Commercial Logic: From Product to Service

Historically, the business model was based on selling a commodity (biodiesel) that had to compete on price with fossil oil—a lost battle due to high production costs (>$5 USD/gallon). Current trends reveal an inversion of this logic toward a service-based model:

- Bioremediation as a Revenue Stream: Technology is shifting toward systems utilizing municipal or industrial wastewater as culture media. In this scheme, the microalgae producer does not pay for water and nutrients (NPK), but rather charges a treatment fee (or gate fee) for cleaning the effluent. Biofuel shifts from being the primary product to a valorizable co-product of a water treatment plant.

- CO₂ Monetization: Integration with industrial flue gas transforms CO₂ from a passive waste into a financial asset. Through Cap-and-Trade schemes, microalgae plants generate additional revenue for every ton of carbon captured, effectively subsidizing the final cost of the biofuel.

Technological Focus: Coupling Systems

Based on patent trends, “stand-alone” technologies (open ponds using freshwater and synthetic fertilizers) are commercially obsolete. The innovation frontier lies in Coupled Systems:

- Energy Coupling: Integration of algae production with biogas plants (Anaerobic Digestion). Solid algal waste (post-lipid extraction) is digested to produce methane, and the liquid digestate (rich in ammonium) is recycled to feed new algae, closing the nutrient loop.

- Industrial Symbiosis: Strategic siting of photobioreactors adjacent to cement or thermoelectric plants for direct flue gas injection, eliminating CO₂ transport and pumping costs.

Conclusion

In summary, the convergence of patent code Y02E and the rise of LCA confirms that microalgal biofuel has ceased to be a direct competitor to oil, becoming an environmental service technology. Future commercial viability lies not in lipid maximization per se, but in system efficiency for providing water treatment and carbon capture, with biofuel acting as an energy vector within a circular economy.

Economic Diversification Strategy: The Cascading Biorefinery Model

The Unviability of the Single-Product Model

Literature analysis and market trends confirm the obsolescence of the “Fuel-Only” paradigm. Techno-Economic Assessments (TEA) in recent literature indicate that the production cost of microalgal biodiesel (>$2–5 USD/L) cannot compete with fossil fuels without massive subsidies. In this sense, the “economic demise” of the pure biodiesel model has forced a field restructuring toward co-production. Biofuel has transitioned from being the flagship product to a waste valorization product within a broader value chain.

Cross-referenced Evidence: Science and Patents

The transition toward multi-production is clearly reflected in the divergence between scientific and technological data:

- In Science: Keyword analysis shows a growing semantic association between energy terms (Biodiesel, Biofuel) and high biological value terms (Proteins, Pigments, Carotenoids, Omega-3). This suggests academic research is prioritizing strains that accumulate not only neutral lipids for burning but also commercially high-value antioxidant metabolites (HVAPs).

- In Technology: The applicant profile validates this strategy. Companies like Mara Renewables (14 families) and Corbion Biotech (21 families) are not traditional oil companies; they are leaders in nutrition and biotechnology. Their patents protect heterotrophic fermentation processes to produce DHA/EPA-rich oils (for supplements and aquaculture). In this model, only the low-quality lipid fraction or residual biomass is allocated for energy use, offsetting global process costs.

The “Cascading” Principle (Downstream Processing)

The dominant technological trend is fractionated processing, where biomass is dismantled sequentially to maximize extracted value. The analysis identifies three critical stages in this new industrial standard:

- Primary Extraction (High Value): Thermosensitive and high-price compounds (e.g., astaxanthin, phycocyanin, or Omega-3 fatty acids) intended for pharmaceutical or cosmetic markets are recovered first.

- Secondary Extraction (Energy): The remaining neutral lipids (TAGs) and carbohydrates are diverted to transesterification for biodiesel or fermentation for bioethanol.

- Tertiary Valorization (Agriculture): Spent biomass (rich in nitrogen and phosphorus) is processed as biofertilizer or agricultural biostimulant, closing the nutrient cycle.

Technological Frontier: Cellular “Milking”

To avoid cell destruction (which forces restarting the culture from scratch), the most innovative patents focus on non-destructive extraction or “milking” technologies. Grira et al. (2023) described that the non-destructive lipid extraction method, known as “milking,” is superior to the conventional biofuel production process from microalgae, identifying the microalga Botryococcus braunii as the most suitable candidate, as it produces high lipid content and has the natural capacity to store them outside the cell (in an extracellular matrix), facilitating extraction without cell death.

Developments are observed in the use of biocompatible solvents and Pulsed Electric Fields (PEF) that temporarily permeabilize the cell membrane, allowing the algae to “excrete” compounds of interest and remain alive for continued production. This transforms cultivation from a batch process to a continuous process, drastically reducing OPEX (Operating Expenses).

Conclusion

In conclusion, the microalgae industry has adopted a risk diversification strategy. Biofuel production has been subordinated to the extraction of high value-added compounds. The viable business model is no longer a ‘biological oil refinery,’ but a nutritional biorefinery that utilizes energy merely as a pathway to valorize its waste and reduce its carbon footprint.

Algal Biofuel Production

Based on scientific and technological insights, four distinct technological pathways for biofuel production have been identified. These are summarized in the table below and detailed in the subsequent paragraphs:

Table 01: Summary of technological pathways for algal biofuel production.

| Method | Final Product | Key Technology | Status |

| Transesterification | Biodiesel (FAME) | Sonication, Solvent Extraction | Mature / Academic |

| Liquefaction (HTL) | Bio-crude | High Pressure/Temperature, Wet Biomass | Emerging / Industrial |

| Fermentation | Bioethanol / Biogas | Enzymatic Hydrolysis, Anaerobic Digestion | Waste Valorization |

| Secretion (Milking) | Oils / Pure Ethanol | Gene Editing (CRISPR), Biocompatible Solvents | Technological Frontier (Patents) |

The Classic Route: Lipid Extraction and Transesterification (Biodiesel)

This conventional process encompasses biomass cultivation, drying (typically), and subsequent cell disruption to release intracellular lipids, which are then chemically transformed. Cell wall rupture constitutes the rate-limiting step of the reaction; therefore, methods such as sonication (ultrasound) and enzymatic hydrolysis are critical for releasing lipids and sugars. Finally, transesterification converts triglycerides into Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (FAME), commercially known as biodiesel.

Regarding extraction efficiency, Mane et al. (2025) demonstrated the superiority of ultrasound-assisted technology over microwave and conventional (Soxhlet) methods in Chlorella genus microalgae. Their findings indicate that optimized pretreatments effectively fracture the cell wall. Consistently, Ray et al. (2025) determined that sonication not only increased lipid productivity by 18% but, when applied in co-cultures, yielded a FAME profile composed of 78% saturated fatty acids, ideal for biodiesel quality.

On the other hand, Shi et al. (2026) propose a process integration: the implementation of a sequential “ultrasound-anaerobic fermentation-lipid extraction” route maximizes simultaneous yields of biohydrogen and biodiesel in species such as Nannochloropsis sp., Chlorella sp., Schizochytrium sp., Thalassiosira sp., and Dunaliella sp.

The Thermochemical Route: Hydrothermal Liquefaction (HTL)

This pathway is critical due to its energy efficiency, as it eliminates the need to dry the algae. By subjecting wet biomass to high pressures and temperatures (geologically simulating petroleum formation in minutes), a bio-crude (bio-oil) is generated, which can be refined into diesel, gasoline, or aviation fuel.

According to Sharma et al. (2021) and Zhang et al. (2022), Hydrothermal Liquefaction (HTL) demonstrates superiority over pyrolysis for wet biomass valorization, allowing the direct conversion of the feedstock—including the aqueous phase—into liquid fuels. In consonance, Neokosmidis (2025) highlights the growing interest in this thermochemical alternative, underscoring two strategic advantages: its capacity to process whole biomass (without relying exclusively on the lipid fraction) and the elimination of pre-drying, an energy-intensive step.

However, process efficiency is multifactorial. While Wang et al. (2026) conclude that, for Chlorella vulgaris, critical parameters are solid load and operating pressure, Sharma et al. (2021) and Costa et al. (2023) maintain that the intrinsic biochemical composition of the feedstock (the microalgae species) constitutes the final determinant of process success.

The Fermentative Route: Bioethanol and Biogas

This route is frequently employed under the Biorefinery concept to valorize residual biomass (the delipidated fraction).

- Bioethanol: Requires the hydrolysis of complex carbohydrates into glucose for subsequent fermentation. Kusmiyati et al. (2023) conclude that enzymatic hydrolysis holds the highest implementation potential due to its low cost, lower energy demand, and reduced environmental impact by dispensing with aggressive chemicals.

- Biogas (Anaerobic Digestion): Utilizes bacterial consortia to decompose biomass in the absence of oxygen, producing methane. It is key to coupling with water treatment. Hawrot-Paw and Tapczewski (2025) highlight that the anaerobic co-digestion of microalgal biomass alongside bakery waste proves more efficient than digesting individual substrates, optimizing energy production.

The Advanced Engineering Route: Secretion and “Milking”

This trend, exclusive to patent analysis and led by institutions like MIT, proposes a paradigm shift: substituting cell lysis (algal death) with non-destructive extraction. Through genetic engineering (CRISPR) or biocompatible solvents, the cell is induced to excrete lipids or ethanol into the culture medium. This allows the system to be transformed into a continuous process, converting the culture into a true “bio-factory.”

De Freitas et al. (2023) point out that it is possible to use genetically modified microalgae to treat effluents from Anaerobic Membrane Bioreactors (AnMBR) while simultaneously generating high-value co-products. Finally, Grira et al. (2023) conclude that the commercial viability of this technology depends on an integral approach: adopting the biorefinery model, designing strains genetically robust against “milking” stress, and employing artificial intelligence to accelerate the development of these bioprocesses.

Benefits of Third-Generation Biofuels

Algal biofuels present significant advantages that transcend mere energy production, offering integral solutions to environmental and socioeconomic challenges:

Climate Change Mitigation and Decarbonization

The most prominent benefit in scientific literature is the capacity of microalgae to sequester CO₂ and reduce the global carbon footprint, aligning with international “Net Zero Emissions” strategies. These microorganisms act as efficient biological sinks, capturing atmospheric or industrial carbon during their photosynthetic process.

Furthermore, Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) demonstrates that algal biofuels can significantly mitigate Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions compared to fossil fuels, especially when production is integrated with renewable energies. In this regard, Mehta et al. (2023) highlight that microalgal bioenergy has the potential to reduce GHG emissions by between 4% and 5%. In prospective terms, Tang et al. (2026) project that, by the year 2035, China will produce 4,395 kilotons of algal biodiesel, entailing a cost reduction of $1.612 billion and an estimated carbon dioxide emissions decrease of 13,165 kilotons annually.

Synergy with Wastewater Treatment

Microalgae possess the dual capacity to proliferate in wastewater, simultaneously resolving sanitation needs and energy generation. This phytoremediation process allows for the removal of nitrogen, phosphorus, and organic pollutants (Chemical Oxygen Demand – COD) from industrial and beverage effluents, drastically reducing costs associated with conventional chemical treatment.

Hasanath et al. (2026) determined that freshwater species such as Scenedesmus obliquus and Chlorella pyrenoidosa are highly effective for treating Beverage Wastewater (BWW), characterized by high COD and low nutrient levels. Consistently, Loni et al. (2026), Raven et al. (2023), and Buzek (2024) validated the use of municipal and industrial effluents as a nutritive medium for bioethanol and other biofuel production. Additionally, Merino et al. (2024) highlighted the potential of valorizing sludge from bay eutrophication for cultivating Scenedesmus acutus for energy purposes.

Efficient Land and Resource Use

Unlike first-generation biofuels (corn, soy, palm), microalgae do not require arable land, thus mitigating the dilemma between food security and energy (“Food vs. Fuel”). Their cultivation is viable in desert zones, arid lands, or at sea. Moreover, they present maximum photosynthetic efficiency, producing between 2 and 15 times more lipids per hectare compared to traditional oilseed crops such as soy and rapeseed (Mehta et al., 2023).

Co-production Capacity (Biorefinery)

A fundamental economic advantage lies in the versatility of algal biomass to generate multiple energy carriers simultaneously under a biorefinery scheme. From the same culture, it is possible to obtain biodiesel (lipid fraction), biohydrogen (fermentative pathway), and biogas (anaerobic digestion of waste). An example of this integration is the study by Shi et al. (2026), who achieved successful co-production of biohydrogen and biodiesel using five distinct microalgae species.

High Productivity and Efficiency

Microalgae exhibit growth and lipid accumulation rates far superior to those of terrestrial plants, with the capacity to double their biomass in a matter of hours. To maximize this efficiency, the use of advanced catalysts is key. Alrudainy et al. (2026) emphasize that Magnetic Nanoparticles (MNPs) represent a transformative technological platform, enabling ecologically and economically viable biodiesel production through catalytic conversion optimization.

Challenges and Technical Limitations in Algal Biofuel Implementation

Despite their undeniable benefits, the commercial viability of algal biofuels faces significant barriers that require resolution prior to mass deployment:

Production Costs

Financial competitiveness remains the most critical constraint, stemming from high capital (CAPEX) and operational (OPEX) expenditures across cultivation, harvesting, and processing stages.

Maroušek et al. (2022) caution that current technological barriers place the hypothetical price of algal biodiesel far from market parity: they estimate a cost of 292 €/100 km, a figure staggeringly disproportionate to the 15.6 €/100 km of conventional fossil fuels.

Along the same lines, Neokosmidis (2025) highlights that microalgae cultivation and harvesting costs are significantly higher than those of terrestrial biomass. Specifically, the estimated average price stands at 2.2 €/L for the lipid extraction pathway and rises to 3.4 €/L for hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL)—values that vastly exceed the costs of fossil fuels or commercial HVO (Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil).

Nevertheless, scenarios of regional viability exist. Quiroz et al. (2023), utilizing validated biophysical and sustainability models, determined that achieving Minimum Selling Prices (MSP) between $1.89 and $2.15 USD per liter of gasoline equivalent (LGE) is feasible in specific regions such as Southeast Asia and Venezuela.

However, these projections must be interpreted with caution; Maroušek et al. (2023) conclude that a significant portion of current research yields economically optimistic results because they rely on linear extrapolations of lab-scale experiments, failing to account for the inherent inefficiencies of industrial scale-up.

Scalability and Biological Variability Challenges

While microalgae offer high theoretical yields, the transition to industrial scale presents substantial technical and logistical challenges requiring massive infrastructure investment. A critical factor in this scale-up is product consistency. El-Sheekh et al. (2024) highlight that the biochemical composition of the biomass—including moisture content, lipids, carbohydrates, proteins, ash concentration, and lignin percentage—directly impacts bioenergy generation efficiency. Controlling these variables in large culture volumes remains a complex endeavor.

Environmental Impact

Paradoxically, mass algae production carries ecological risks if not properly managed. The intensive use of synthetic fertilizers in open systems can lead to the eutrophication of adjacent water bodies due to nutrient runoff. Therefore, it is imperative to implement sustainable practices, such as culture medium recycling and strict compliance with discharge regulations, to mitigate these collateral effects.

Technical Performance in Combustion Engines

Various studies have pointed out operational limitations in the direct use of algal biodiesel, attributed mainly to its lower calorific value and higher kinematic viscosity compared to petrochemical diesel, which can result in incomplete combustion or injection issues.

However, emerging nanotechnological solutions exist. Meraz et al. (2023) report that incorporating nano-additives into algal biodiesel blends significantly improves combustion characteristics, increases calorific value, and optimizes overall engine performance, overcoming the deficiencies of the pure biofuel.

Chemistry of Algal Biofuels

The chemistry of algal biofuels is complex, involving various reactions to convert biomass into usable fuels. Key aspects of algal biofuel chemistry are described below:

- Photosynthesis: Algae utilize photosynthesis to convert sunlight into biomass, producing oxygen and glucose. This biomass is rich in lipids, carbohydrates, and proteins.

- Lipid Extraction: Lipids are extracted from algal biomass using physical or chemical methods. The extracted lipids are primarily triglycerides, which can be converted into biodiesel.

- Transesterification: This chemical process converts triglycerides into biodiesel and glycerol via reaction with an alcohol—typically methanol—in the presence of a catalyst.

- Fermentation: Carbohydrates present in algal biomass can be fermented to produce bioethanol, which serves as fuel for internal combustion engines.

For a more detailed description of algal biofuel chemistry, refer to the work by Alazaiza et al. (2023). Additionally, scientists at RUDN University have evaluated the most efficient processes for obtaining biofuels from algae.

Uses and Applications of Algal Biofuels

Aviation: Sustainable Aviation Fuels (SAF)

The application holding the highest strategic value and growth potential for microalgal biofuels lies in the decarbonization of the aeronautical sector. Unlike light-duty road transport, which is rapidly transitioning toward electrification, aviation intrinsically relies on high-energy-density liquid fuels. Microalgae, processed via Hydrothermal Liquefaction (HTL), allow for the production of Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF), a drop-in synthetic kerosene.

This characteristic allows for its direct blending with fossil Jet A-1 without requiring modifications to turbines, positioning it as the only scalable solution that does not compromise food security by avoiding competition for arable land.

Heavy-Duty Road and Maritime Transport

Parallelly, freight transport and the maritime sector remain key consumers, supported by the classic technological route. In this segment, algal lipids are transformed into biodiesel (FAME) for conventional blends or, through hydrotreating processes, into Renewable Diesel (HVO).

The latter product is chemically indistinguishable from fossil diesel, enabling its use at 100% blends in marine and heavy-duty engines. This eliminates corrosion and oxidative stability issues associated with first-generation biodiesels, offering an immediate transition for logistics fleets.

Stationary Generation and Chemical Industry

Finally, the consolidation of the biorefinery model has diversified applications toward stationary generation and chemical synthesis. The anaerobic digestion of residual biomass or its coupling with wastewater treatment generates biomethane, suitable for injection into natural gas grids or for in-situ Combined Heat and Power (CHP) generation, conferring energy self-sufficiency to treatment plants.

Likewise, emerging technologies such as dark fermentation and biophotolysis are fostering the rise of biohydrogen, a clean energy vector destined to fuel cells and to decarbonize intensive industrial processes, such as steel and fertilizer production.

Table 02: Applications and sectors of Microalgal Biofuels.

| Primary Use | Fuel Type | Application Sector | Technological Pathway (Basis) |

| Sustainable Aviation | Bio-Jet Fuel (SAF) / Synthetic Kerosene | Commercial and Military Aviation (Turbines) | Thermochemical (HTL): Allows obtaining high-energy-density “drop-in” fuels from wet biomass. |

| Heavy Transport | Biodiesel (FAME) and Green Diesel (HVO) | Freight Trucks, Buses, Agricultural and Maritime Machinery | Classic (Lipids): Transesterification of extracted oils. |

| Energy Autonomy | Biogas (Biomethane) and Electricity | Industrial Heating, Gas Grid, Self-consumption in Treatment Plants | Fermentative (Anaerobic Digestion): Valorization of waste and whole biomass (Purple Cluster). |

| Clean Mobility | Biohydrogen (Bio-H2) | Fuel Cells (FCEV), Chemical Industry (Green Ammonia) | Bio-photolysis/Fermentation: Advanced ultrasound-assisted processes. |

| Regenerative Agriculture | Digestate and Biostimulants | Soil Fertilization, Nutrient Recovery (N, P) | Cascading Biorefinery: Use of post-extraction residual biomass to close the nutrient loop. |

Future of Third-Generation Biofuels

The future of algal biofuels is contingent upon overcoming current technical and economic barriers. However, with the backing of strategic government policies, sustained investment in R&D, and the implementation of disruptive technologies, these biofuels retain the potential to play a pivotal role in the transition toward a sustainable energy matrix.

Regarding technological evolution, Moriarty & Honnery (2024) project continuous progress in both strain selection and production engineering. However, the authors caution against making isolated energy forecasts: the success of algae will depend on their relative speed of innovation vis-à-vis competing technologies, specifically photovoltaics and, potentially, direct photolysis.

As for research priorities, Wołejko et al. (2023) recommend focusing future efforts on the simultaneous maximization of fuel yield and quality, without neglecting economic viability. Complementarily, Coşgun et al. (2023) underscore the transformative potential of Machine Learning to optimize the critical stages of detecting and selecting ideal strains.

Finally, a comprehensive analysis of scientific literature and patent trends suggests that the future of the third generation does not lie in the mass production of biodiesel as a low-cost commodity, but in its transformation into a high-tech industry grounded in three fundamental pillars:

- Synthetic Biology and Cellular “Milking”: A paradigm shift from natural selection toward laboratory-designed microalgae with edited metabolic pathways. The goal is to surpass natural photosynthetic limits and enable continuous lipid secretion, dispensing with cell lysis (algal death) and enabling uninterrupted production processes.

- Symbiotic Integration and Circular Economy: Cultivation plants will evolve into sanitation service hubs. The business model will be based on the monetization of wastewater treatment and industrial CO₂ capture. In this scheme, biofuel becomes a valorizable byproduct whose production cost is cross-subsidized by the environmental remediation service.

- Hybrid and Autonomous Biorefinery: Facilities will operate under the “Cascading Biorefinery” concept, producing a diversified portfolio (biohydrogen, biodiesel, fertilizers) rather than a single fuel. Furthermore, they will integrate with exogenous renewable sources (solar/geothermal) to neutralize their operational carbon footprint.

Ultimately, third-generation biofuels will cease to compete with oil in terms of “price per barrel” to consolidate themselves as an indispensable biotechnological platform for industrial decarbonization and waste management, founded on genetically optimized organisms.

Conclusion

In conclusion, algae emerge as a decisive element in resolving the historical dilemma between food security and energy production (Mahmood et al., 2023). Third-generation biofuels constitute not only an innovative solution but a systemic response to 21st-century sustainability challenges. In this sense, the report’s main conclusions are:

- Business Model Shift (From Product to Service): Algal biofuel production is no longer viewed as direct price competition against oil. The new economic model is based on the provision of environmental services: wastewater treatment and industrial CO₂ capture. Biofuel becomes a valorizable byproduct within a circular economy system, subsidized by revenue from environmental remediation.

- Technological Evolution toward Synthetic Biology: Research has transitioned from simple natural strain selection (“bioprospecting”) to active organism design via genetic engineering and CRISPR. The current focus, backed by MIT and Broad Institute patents, seeks to create cellular “bio-foundries” capable of continuously secreting lipids (“milking” technology), avoiding biomass destruction and reducing costs.

- The Cascading Biorefinery as Standard: The “mono-product” model (biodiesel only) is financially obsolete. Future viability depends on fractionated or cascading processing: first extracting commercially high-value compounds (Omega-3, antioxidants), then producing liquid biofuels, and finally using residues as biofertilizers or biogas. This maximizes the value of every gram of biomass.

- Scientific Maturity and Holistic Approach: Bibliometrics reveal that science has surpassed the “laboratory optimization” stage (how to extract oil) to focus on systemic sustainability (Life Cycle Assessment – LCA). Current technology validation depends more on its Net Energy Balance (NEB) and actual capacity to reduce Greenhouse Gases (GHG) than on simple fuel volume produced.

While technical and financial challenges persist, the balance of their environmental and socioeconomic benefits consolidates them as a strategic alternative to fossil fuels. It is projected that, as the technology matures and production costs are optimized, their widespread adoption will act as an indispensable catalyst for achieving a cleaner and more resilient energy future.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How do algal biofuels (third generation) differ from previous generations?

Third-generation biofuels are produced from microalgae and macroalgae cultivated in aquatic systems (such as photobioreactors or ponds), as opposed to first-generation fuels derived from food crops (corn, soy). Their primary advantage lies in their lack of competition for arable land, ensuring they do not compromise food security. Additionally, they demonstrate superior photosynthetic efficiency and rapid growth rates, enabling the generation of biodiesel, bioethanol, biohydrogen, and biogas via the conversion of solar energy into biomass.

What are the main technological pathways for producing these fuels?

The text identifies four primary pathways:

– Transesterification: A classic method employing ultrasound for cell disruption and lipid extraction to produce biodiesel.

– Hydrothermal Liquefaction (HTL): Processes wet biomass under high pressure and temperature to create “bio-crude,” ideal for aviation fuel.

– Fermentation: Converts carbohydrates into bioethanol or waste residues into biogas.

– Secretion (“Milking”): A frontier technology utilizing gene editing or solvents to “milk” the cell without killing it, enabling continuous production.

Why is integrating biofuel production with wastewater crucial?

Integration is vital for economic viability. Cultivating microalgae in municipal or industrial wastewater significantly reduces Operating Expenses (OPEX) by eliminating the need to purchase freshwater and synthetic fertilizers. Algae perform phytoremediation, removing nitrogen and phosphorus from the water while simultaneously producing energetic biomass. This effectively transforms treatment plants into Circular Economy Biorefineries.

What role does genetic engineering play in the future of this industry?

There has been a paradigm shift from bioprospecting wild strains toward Synthetic Biology. Leading institutions like MIT and the Broad Institute are employing tools such as CRISPR-Cas9 to rewrite the algal genome. The objectives are to maximize lipid yields, optimize photosynthesis, and enable non-destructive extraction of compounds, thereby surpassing natural productivity limits.

Are they economically competitive with fossil fuels?

Currently, the production cost of pure algal biodiesel (estimated in some instances at > $2–5 USD/liter) is not competitive with petroleum without subsidies. Current trends indicate that the viable business model is not a “fuel-only” approach, but a service-based scheme: charging for wastewater treatment, selling carbon credits, and extracting high-value compounds (nutraceuticals) first, before utilizing the residual biomass for energy.

What trends do patents reveal about innovation in the sector?

Patent analysis shows that Intellectual Property is concentrated on:

– Biological Design: Genetically modified strains (led by U.S. universities).

– Climate Mitigation: Technologies explicitly designed for carbon capture (code Y02E).

– Cultivation Systems: Advanced photobioreactors.

This confirms that the industry prioritizes cellular productivity and environmental sustainability over mere extraction machinery.

References

Alazaiza, M. Y., Albahnasawi, A., Al Maskari, T., Abujazar, M. S., Bashir, M. J., Nassani, D. E., & Abu Amr, S. S. (2023). Biofuel Production Using Cultivated Algae: Technologies, Economics, and Its Environmental Impacts. Energies, 16(3), 1316. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16031316

Alrudainy, A. M., Alnuaimi, M. T., Amshawee, A. M., Ali, R., Thanon, K. S., & Alassadi, N. M. (2026). Magnetic nanoparticles as recyclable catalysts in biodiesel synthesis from microalgae. Sustainable Chemistry One World, 9, 100164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scowo.2025.100164

Buzek, P. (2024, May). Concept design of a power plant using algae biofuels. In 62nd International Conference of Machine Design Departments (ICMD 2022) (pp. 322-328). Atlantis Press.

Coşgun, A., Günay, M. E., & Yıldırım, R. (2023). Machine learning for algal biofuels: a critical review and perspective for the future. Green Chemistry, 25(9), 3354-3373.

Costa, P. A., Mata, R. M., Pinto, F., Paradela, F., Duarte, R., & Matos, C. (2023). Effect of type of biomass used in the hydrothermal liquefaction of microalgae on the bio crude yields and quality. Chemical Engineering Transactions, 99, 31-36.

De Freitas, B. B., Overmans, S., Medina, J. S., Hong, P., & Lauersen, K. J. (2023). Biomass generation and heterologous isoprenoid milking from engineered microalgae grown in anaerobic membrane bioreactor effluent. Water Research, 229, 119486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2022.119486

El-Sheekh, M. M., El-Chaghaby, G. A., & Rashad, S. (2023). Bioenergy production from algae: Biomass sources and applications. Green Approach to Alternative Fuel for a Sustainable Future, 59-69. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-824318-3.00032-1

Flach, B., von Witzke, K., & Bolla, S. (2025). Biofuels Annual: European Union (Report No. E42025-0004). United States Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Service

Grira, S., Abu Khalifeh, H., Alkhedher, M., & Ramadan, M. (2023). The conventional microalgal biofuel production process and the alternative milking pathway: A review. Energy, 277, 127547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2023.127547

Hasanath, M. A., Panigrahi, A., Chaitanya, N. K., & Chatterjee, P. (2026). Treatment of beverage wastewater using microalgae: A focus on COD removal, biomass production, and lipid accumulation. Bioresource Technology Reports, 33, 102467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biteb.2025.102467

Hawrot-Paw, M., & Tapczewski, J. (2025). Waste to Energy: Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Microalgal Biomass and Bakery Waste. Energies, 18(20), 5516. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18205516

Kusmiyati, K., Hadiyanto, H., & Fudholi, A. (2023). Treatment updates of microalgae biomass for bioethanol production: A comparative study. Journal of Cleaner Production, 383, 135236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.135236

Loni, S., Shinde, A., Kshirsagar, R., Tanwar, M., & Guldhe, A. (2026). Integration approach of microalgae cultivation with biomethanation derived wastewater as nutrient source for sustainable bioethanol production. Bioresource Technology, 441, 133548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2025.133548

Mahmood, T., Hussain, N., Shahbaz, A. et al. Sustainable production of biofuels from the algae-derived biomass. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng 46, 1077–1097 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00449-022-02796-8

Mane, S., Singh, A. & Taneja, N.K. Pretreatment optimization for microalgae oil yield enhancement and residual biomass characterization for sustainable biofuel feedstock production. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 15, 9859–9874 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-024-05768-y

Maroušek, J., Strunecký, O., Bartoš, V., & Vochozka, M. (2022). Revisiting competitiveness of hydrogen and algae biodiesel. Fuel, 328, 125317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2022.125317

Maroušek, J., Maroušková, A., Gavurová, B., Tuček, D., & Strunecký, O. (2023). Competitive algae biodiesel depends on advances in mass algae cultivation. Bioresource Technology, 374, 128802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2023.128802

Mehta, P., Sahil, K., Sarao, L.K., Jangra, M.S., Bhardwaj, S.K. (2023). Algal Biofuels: Clean Energy to Combat the Climate Change. In: Srivastava, N., Mishra, P. (eds) Basic Research Advancement for Algal Biofuels Production. Clean Energy Production Technologies. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-6810-5_7

Meraz, R. M., Rahman, M. M., Hassan, T., Al Rifat, A., & Adib, A. R. (2023). A review on algae biodiesel as an automotive fuel. Bioresource Technology Reports, 24, 101659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biteb.2023.101659

Merino, F., Mendoza, S., Carhuapoma-Garay, J. et al. Potential use of sludge from El Ferrol Bay (Chimbote, Peru) for the production of lipids in the culture of Scenedesmus acutus (Meyen, 1829). Sci Rep 14, 6968 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-52919-2

Moriarty, P., & Honnery, D. (2024). Microalgal based biofuels: Sources, benefits, and constraints. Microalgal Biomass for Bioenergy Applications, 23-40. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-443-13927-7.00012-8

Muthuraman, V. S., & Kasianantham, N. (2023). Valorization opportunities and adaptability assessment of algae based biofuels for futuristic sustainability-A review. Process Safety and Environmental Protection, 174, 694-721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2023.04.043

Neeti, K., Gaurav, K., & Singh, R. (2023). The Potential of Algae Biofuel as a Renewable and Sustainable Bioresource. Engineering Proceedings, 37(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/ECP2023-14716

Neokosmidis, T. (2025). Algae to Liquid Biofuels – State of Industry and Technology Literature Review (Reporte n.º 3/25). Concawe.

OECD/FAO. (2025). OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2025-2034. OECD Publishing, París / Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura (FAO), Roma.,. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1787/601276cd-en

Pires, R., Silva, T. P., Ribeiro, C., Costa, L., Matos, C. T., Costa, P., Lopes, T. F., Gírio, F., & Silva, C. (2024). Carbon footprint assessment of microalgal biomass production, hydrothermal liquefaction and refining to sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) in mainland Portugal. Algal Research, 84, 103799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.algal.2024.103799

Quiroz, D., Greene, J. M., Limb, B. J., & Quinn, J. C. (2023). Global Life Cycle and Techno-Economic Assessment of Algal-Based Biofuels. Environmental Science & Technology, 57(31), 11541-11551.

Raven, S., Noel, A.A., Tirkey, J.F., Tiwari, A. (2023). Recent Advancements in Municipal Wastewater as Source of Biofuels from Algae. In: Srivastava, N., Mishra, P. (eds) Basic Research Advancement for Algal Biofuels Production. Clean Energy Production Technologies. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-6810-5_1

Ray, B., Jayakumar, T. & Rakesh, S. Comparative analysis of lipid content in mono and co-culture microalgae for potential biodiesel production using diverse cell disruption techniques. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 15, 26857–26865 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-023-04482-5

Ruales, E., Gómez-Serrano, C., Morillas-España, A., Garfí, M., González-López, C. V., & Ferrer, I. (2025). Microalgae-based biorefinery for biostimulant and biogas production: An integrated approach for resource recovery. Algal Research, 91, 104323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.algal.2025.104323

Sarwan, J., Nair, M. V., Sharma, S., Uddin, N., & Bose, K. J. C. 2024. Omics Technology Approaches for the Generation of Biofuels. In Biomass Energy for Sustainable Development (pp. 165-191). CRC Press.

Sharma, N., Jaiswal, K. K., Kumar, V., Vlaskin, M. S., Nanda, M., Rautela, I., Tomar, M. S., & Ahmad, W. (2021). Effect of catalyst and temperature on the quality and productivity of HTL bio-oil from microalgae: A review. Renewable Energy, 174, 810-822. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2021.04.147

Shi, Y., Wang, R., Tian, E., Xing, Y., Li, F., & Lu, Z. (2026). Co-production of biohydrogen and biodiesel from different microalgae by ultrasound, anaerobic fermentation and lipid extraction. Renewable Energy, 258, 125014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2025.125014

Tang, Y., Jiang, Y., Hu, Y., & Cheng, Y. (2026). Carbon emission reduction potential analysis of biodiesel production from microalgae and waste cooking oil under different SSPs scenarios in China-based on GRA-CNN-BiLSTM modeling. Renewable Energy, 258, 125006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2025.125006

Wang, Z., Zhao, Z., Elendu, C. C., & Duan, P. (2026). Feedstock loading and pressure synergy in high-solid microalgae HTL: Boosting bio-oil yield while reducing nitrogen content. Biomass and Bioenergy, 204, 108460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2025.108460

Wołejko, E., Ernazarovna, M. D., Głowacka, A., Sokołowska, G., & Wydro, U. (2023). Using Algae for Biofuel Production: A Review. Energies, 16(4), 1758. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16041758

Zhang, B., Huang, J., Chen, H., & He, Z. (2022). Reducing nitrogen content in bio-oil from hydrothermal liquefaction of microalgae by using activated carbon-pretreated aqueous phase as the solvent. Biomass and Bioenergy, 167, 106638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2022.106638

Editor at the digital magazine AquaHoy. He holds a degree in Aquaculture Biology from the National University of Santa (UNS) and a Master’s degree in Science and Innovation Management from the Polytechnic University of Valencia, with postgraduate diplomas in Business Innovation and Innovation Management. He possesses extensive experience in the aquaculture and fisheries sector, having led the Fisheries Innovation Unit of the National Program for Innovation in Fisheries and Aquaculture (PNIPA). He has served as a senior consultant in technology watch, an innovation project formulator and advisor, and a lecturer at UNS. He is a member of the Peruvian College of Biologists and was recognized by the World Aquaculture Society (WAS) in 2016 for his contribution to aquaculture.