The Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) is one of the most important species in marine aquaculture. As the demand for salmon continues to grow, the aquaculture industry faces the challenge of finding sustainable protein sources for fish feed.

Traditional protein sources, such as fishmeal, are becoming increasingly scarce due to overfishing and environmental concerns. In response, researchers are exploring alternative protein sources that can support the industry’s growth while minimizing environmental impact. A literature review conducted by researchers from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology sheds light on the most promising alternative protein sources for Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) feed, focusing on their carbon footprint and sustainability.

- 1 The need for alternative protein sources

- 2 Insect proteins: A promising alternative

- 3 Single-Cell proteins: microalgae, yeasts, and bacteria

- 4 Marine proteins: Blue mussels and krill

- 5 Terrestrial animal by-products: poultry and feather meal

- 6 Plant-based proteins: camelina and lupin

- 7 Conclusion: Towards a sustainable salmon industry

- 8 Entradas relacionadas:

The need for alternative protein sources

The global aquaculture industry is expanding rapidly, along with the demand for protein-rich fish feed. Fishmeal is no longer sustainable due to the overexploitation of marine resources. Plant-based proteins, such as soybean meal, have partially replaced fishmeal, but they come with their own challenges.

The intensive cultivation of crops for plant-based feed has led to land conversion, increased fertilizer use, and competition with human food supplies. Additionally, some plant-based ingredients can negatively affect fish health, causing issues such as soybean meal-induced enteropathy (SBMIE) in salmon.

To address these challenges, researchers are investigating alternative protein sources that are both nutritionally adequate and environmentally sustainable. These alternatives include insect proteins, single-cell proteins, marine proteins, terrestrial animal by-products, and plant-based proteins. The review by Cantillo and Deshpande, published in Aquaculture Reports, systematically evaluates these options, focusing on their carbon footprint and potential for sustainable aquaculture.

Insect proteins: A promising alternative

Insects were the most studied protein source in the selected literature. They are a natural component of many fish species’ diets, making them a nutritionally suitable and sustainable option for future aquaculture feed production. Three main types were identified: black soldier fly larvae (Hermetia illucens), yellow mealworm (Tenebrio molitor), and the lesser mealworm (Alphitobius diaperinus), with black soldier fly larvae being the most studied option.

Studies have shown that replacing fishmeal or soybean protein concentrate with black soldier fly larvae meal does not significantly impact growth performance, health, feed pellet physical quality, feed utilization, protein and fat digestibility, intestinal structure, fillet quality, or sensory evaluation of the fillet. Additionally, feeding salmon with black soldier fly larvae meal has been suggested to increase gut microbiota richness and diversity. Consumers have also shown positive acceptance of black soldier fly larvae in salmon feed, and sustainability results are strong compared to other aquafeed protein sources.

However, the carbon footprint of insect protein production varies depending on the substrate used for rearing and the energy required for processing. For instance, using organic waste as a substrate can significantly reduce the carbon footprint, but current regulations in many countries restrict the use of such waste in fish feed. Despite these challenges, the insect protein industry is growing, with over a billion euros invested in insect companies, indicating strong potential for future expansion.

Single-Cell proteins: microalgae, yeasts, and bacteria

Single-cell proteins were the second most studied alternative protein source. These organisms grow rapidly, have high protein content, and can be produced in controlled environments at a reasonable cost. Three types were highlighted: microalgae, yeasts, and bacteria.

Stay Always Informed

Join our communities to instantly receive the most important news, reports, and analysis from the aquaculture industry.

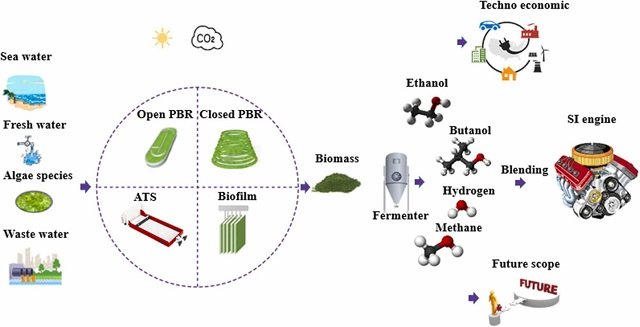

Microalgae require low volumes of freshwater and can be produced alongside other industrial food production processes using secondary biomass inputs such as CO₂, waste heat, and organic by-products. Some species have high protein content, exceeding 50% dry weight, and their amino acid profiles are comparable to those of soybean protein. Studies were found on Nannochloropsis sp., Phaeodactylum tricornutum, Tetraselmis sp., and Chlorella vulgaris.

Yeast was also identified as a significant single-cell protein source. The crude protein content of yeasts ranges from 380 to 600 g kg⁻¹ (dry matter), representing about 40%-55% of yeast biomass, comparable to soybean meal but lower than fishmeal.

Bacteria represent another category of studied single-cell proteins. P. acidilactici meal was found to have no impact on head kidney gene expression in Atlantic salmon, suggesting it is a good fishmeal substitute. The potential of M. extorquens, Escherichia coli, and Spirulina was also investigated.

The carbon footprint of single-cell proteins depends on factors such as energy consumption during cultivation, the type of carbon source used, and production process efficiency. For example, microalgae production can be energy-intensive, particularly if fossil fuels are used for electricity generation. However, using renewable energy sources and optimizing cultivation techniques can significantly reduce environmental impact. Yeast and bacterial proteins are also promising, with studies indicating they can replace traditional protein sources without compromising fish health or growth.

Marine proteins: Blue mussels and krill

Marine proteins were the third most studied protein source. These include blue mussel meal, mesopelagic biomass (jellyfish, krill, shrimp, and mesopelagic fish), northern shrimp (Pandalus borealis) hydrolysate, and Calanus finmarchicus hydrolysate. The inclusion of these proteins in salmon diets has shown positive effects.

Macroalgae (seaweed), such as Laminaria digitata and Saccharina latissima, were also mentioned as marine protein sources. Protein content varies among species, with red algae generally having the highest levels.

The carbon footprint of marine proteins is influenced by factors such as energy consumption during processing and fuel use during harvesting. For example, drying macroalgae protein concentrate can be energy-intensive, but using cleaner energy sources can mitigate this impact. Despite their potential, marine proteins remain a cleaner energy source compared to others.

Terrestrial animal by-products: poultry and feather meal

Terrestrial animal by-products, such as poultry meal and hydrolyzed feather meal, are already used in salmon feed in some regions. These by-products have high protein content and an amino acid profile similar to fishmeal.

However, their use is limited by regulatory restrictions and consumer acceptance issues. The carbon footprint of these proteins is primarily influenced by the rendering process and feed production for poultry farming.

Plant-based proteins: camelina and lupin

Plant-based proteins, such as camelina (Camelina sativa) meal and white lupin (Lupinus albus), are already used in salmon diets but have room for further optimization. Camelina meal, for example, has been shown to perform similarly to fishmeal in terms of growth performance and body composition. However, high inclusion rates can have negative effects on fish health.

The carbon footprint of plant-based proteins is influenced by factors such as fertilizer use and land conversion, but more sustainable agricultural practices can reduce their environmental impact.

Conclusion: Towards a sustainable salmon industry

The review by Cantillo and Deshpande highlights the potential of alternative protein sources to support the sustainable growth of Atlantic salmon aquaculture. Insect proteins, single-cell proteins, marine proteins, terrestrial animal by-products, and plant-based proteins offer viable alternatives to traditional fishmeal. However, their environmental impact varies depending on production methods, energy sources, and regulatory frameworks.

To achieve truly sustainable aquaculture, further research and technological advancements are needed to optimize the production of these alternative proteins. Cleaner energy sources, more efficient cultivation techniques, and innovative processing methods can help reduce the carbon footprint of fish feed. Additionally, regulatory changes may be necessary to allow the use of organic waste and other sustainable substrates in fish feed production.

The study was partly funded by the “Enhancing the potential of Calanus as raw material for sustainable aquaculture feed ingredients – CalaFeed” project, supported by the Norwegian Research Council (2021-2024) under the Collaborative and Knowledge-building Project framework.

Contact

Javier Cantillo

Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Department of Industrial Economics and Technology Management

Trondheim, Norway

Email: javier.cantillo@ntnu.no

Reference (open access)

Cantillo, J., & Deshpande, P. C. (2025). Carbon footprint of alternative protein sources for Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) aquaculture: A two-step systematic literature review. Aquaculture Reports, 40, 102601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aqrep.2024.102601

Editor at the digital magazine AquaHoy. He holds a degree in Aquaculture Biology from the National University of Santa (UNS) and a Master’s degree in Science and Innovation Management from the Polytechnic University of Valencia, with postgraduate diplomas in Business Innovation and Innovation Management. He possesses extensive experience in the aquaculture and fisheries sector, having led the Fisheries Innovation Unit of the National Program for Innovation in Fisheries and Aquaculture (PNIPA). He has served as a senior consultant in technology watch, an innovation project formulator and advisor, and a lecturer at UNS. He is a member of the Peruvian College of Biologists and was recognized by the World Aquaculture Society (WAS) in 2016 for his contribution to aquaculture.