Feed sustainability is one of the most critical dialogues in modern aquaculture. As the sector seeks to reduce its environmental footprint, the concept of “circularity” is emerging as a fundamental roadmap. A recent scientific review article—published by researchers from IFFO, the University of Guelph, the Norwegian University of Life Sciences, CSIRO Agriculture and Food, and the Universidade Do Porto, among other scientific organizations—explores how a circular economy framework, particularly the one proposed in the European Union, can be applied to feed ingredients, laying the groundwork for a more resilient and efficient future.

This approach does not focus on a single “miracle” ingredient but instead addresses the complex challenges facing the feed industry. The goal is clear: to produce high-quality aquafeeds in a cost-effective and environmentally sustainable manner, transforming the way we view and utilize resources.

- 1 Key takeaways

- 2 The four pillars of circularity in feed

- 3 The complex puzzle of ingredient selection

- 4 The importance of knowing what’s in the bag: Nutritional characterization

- 5 The global dilemma: The competition between food, feed, and fuel

- 6 Towards a circular feed system: Turning waste into resources

- 7 Measuring sustainability: Beyond greenwashing

- 8 A conclusion for the future: Collaboration and communication

- 9 Entradas relacionadas:

Key takeaways

- Four-pillar framework: Feed sustainability can be framed by four key principles: minimizing the use of human-edible resources, reducing reliance on land use, maximizing the use of local ingredients, and optimizing nutritional characteristics.

- Characterization is crucial: Circular ingredients cannot be used without a thorough understanding of their nutritional value, digestibility, and potential risks. Analytical precision is fundamental.

- The food-feed competition is a real challenge: A significant portion of feed ingredients competes with human food. Circularity aims to mitigate this by valorizing by-products and waste streams.

- Sustainability must be measurable: To avoid “greenwashing,” it is essential to use standardized tools like Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) to objectively evaluate and compare the environmental impact of ingredients.

- Communication is essential: The success of the transition to a circular bioeconomy depends on transparent and coordinated communication throughout the value chain to overcome biases and gain societal acceptance.

The four pillars of circularity in feed

The European framework for applying circular ingredients is based on four fundamental principles that guide decision-making:

- Minimize the use of food-grade resources: Prioritize the use of ingredients that do not directly compete with human food.

- Minimize reliance on land use: Seek to reduce pressure on terrestrial ecosystems, a key factor in the carbon footprint of many plant-based ingredients.

- Maximize the use of locally sourced ingredients: Promote food security, reduce the transportation footprint, and support regional economies.

- Optimize nutritional characteristics: Ensure that any circular ingredient is not only sustainable but also nutritionally valuable and safe for the animal.

In this regard, Dr. Brett Glencross, Technical Director at IFFO, stated: “One of the key drivers for circularity is the need to improve the sustainability of using ingredients for compound feed. This review demonstrates that it is possible to take a more holistic approach to sustainable feed and food production, particularly through Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) methodologies. By applying a set of common, agreed-upon standards, we can ensure that environmental burdens are not simply shifted from one product to another.”

The complex puzzle of ingredient selection

For a new ingredient, whether circular or not, to be commercially adopted, it must overcome a series of barriers. It is not just about being “sustainable” but about being viable in the real world. Key criteria include:

- Cost-effectiveness: It must offer nutritional value equal to or greater than the ingredient it replaces, at a competitive cost.

- Availability and consistency: A stable supply (over 10,000 tons is a general target) and consistent nutritional composition are needed to avoid affecting feed quality and fish health.

- Bioavailable nutritional profile: It must be rich in essential nutrients like amino acids, fatty acids, or bioactive compounds that the animal can effectively absorb and utilize.

- Safety and low impact: It must comply with food safety standards and come from sources that do not contribute to problems like deforestation.

The importance of knowing what’s in the bag: Nutritional characterization

A fundamental pillar of circularity is that “fish require nutrients, not ingredients.” Therefore, it is useless to produce a circular ingredient if its nutritional characteristics undermine the ability to formulate a balanced feed.

This requires a comprehensive characterization that goes beyond a simple, crude protein analysis. It is crucial to define the digestibility of nutrients—that is, what portion can actually be utilized by the animal. This task, however, faces challenges, as many current analytical methods are outdated and can lead to errors, for instance, in estimating the true protein content or in evaluating amino acids.

The global dilemma: The competition between food, feed, and fuel

One of the greatest sustainability challenges is the competition for resources. Globally, 41% of grain production was allocated to animal feed in 2022, a percentage similar to that destined for human consumption (38%). This pressure on arable land is intensified by the demand for biofuels.

In comparison, the direct use of fish for feed production is considerably lower: only 9% of the total global fish production is used for this purpose. The shift from marine to plant-based ingredients in aquaculture has increased competition for human food resources. A truly circular system seeks to break this cycle by prioritizing resources and valorizing streams that would otherwise be lost.

Stay Always Informed

Join our communities to instantly receive the most important news, reports, and analysis from the aquaculture industry.

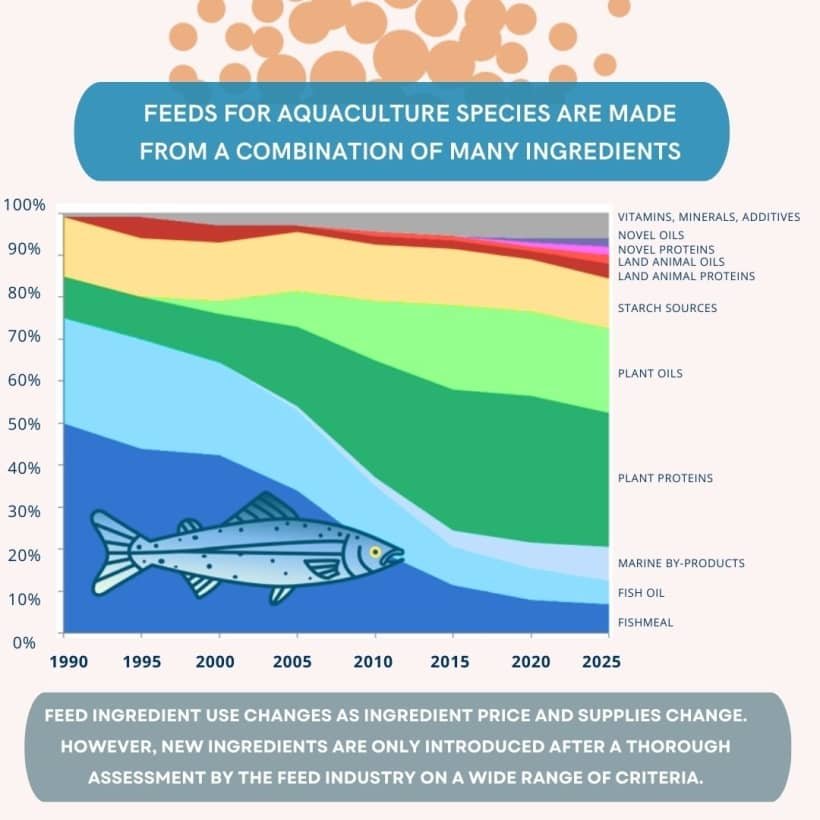

The paper highlights that aquafeeds are now predominantly composed of plant-based raw materials. This shift has significantly reduced the reliance on marine ingredients from 25% to an average of 9% over the last two decades, but it has also linked global aquafeed production to the broader social and environmental impacts of agriculture, including increased impacts on biodiversity and carbon emissions.

Towards a circular feed system: Turning waste into resources

The key to mitigating the “food-feed-fuel” competition is to manage resources more efficiently. This involves adopting a hierarchy that prioritizes human food, minimizes waste, and recycles by-products.

This is where innovation plays a starring role. Technologies like fermentation or the use of microbes and insects can “upcycle” low-value by-products, reintroducing valuable nutrients into the food chain. For example, filamentous fungi like Pekilo can convert agricultural and forestry by-products into high-value protein ingredients that improve feed efficiency in salmon.

Measuring sustainability: Beyond greenwashing

In a market saturated with “green” claims, sustainability must be quantifiable. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) has established itself as the most accepted method for objectively evaluating the environmental impacts of a product. Tools like the Global Feed Lifecycle Assessment Institute (GFLI) database allow for the comparison of ingredients using a standardized methodology.

This opens the door to formulating feeds not only based on their cost and nutritional value but also on their carbon footprint. An example in Atlantic salmon shows that it is possible to reduce a feed’s carbon footprint by 33% with only a 1.2% increase in cost, simply by changing the ingredient selection.

A conclusion for the future: Collaboration and communication

Applying a circularity framework to aquafeeds is a powerful strategy, but it is not without its challenges. It requires rigorous characterization of ingredients, an honest assessment of sustainability, and a re-evaluation of how we allocate global resources.

However, the success of this transition depends not only on technology or science. Effective and transparent communication throughout the entire value chain—from producers to consumers—is essential to build trust and overcome negative perceptions. The responsibility is shared, and only through collaboration can we build a feed industry that is truly circular, sustainable, and prepared for the challenges of the future.

Contact

Brett Glencross

IFFO – the Marine Ingredients Organisation

London, United Kingdom

Institute of Aquaculture, University of Stirling

Stirling, United Kingdom

Email: bglencross@iffo.com

Reference (open access)

Glencross, B., Bureau, D., Øverland, M., Simon, C., Valente, L. M. P., Gracey, E., & Zatti, K. (2025). Toward Applying a Circularity Framework Against the Use of Aquaculture Feed Ingredients. Reviews in Fisheries Science & Aquaculture, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/23308249.2025.2552166

Editor at the digital magazine AquaHoy. He holds a degree in Aquaculture Biology from the National University of Santa (UNS) and a Master’s degree in Science and Innovation Management from the Polytechnic University of Valencia, with postgraduate diplomas in Business Innovation and Innovation Management. He possesses extensive experience in the aquaculture and fisheries sector, having led the Fisheries Innovation Unit of the National Program for Innovation in Fisheries and Aquaculture (PNIPA). He has served as a senior consultant in technology watch, an innovation project formulator and advisor, and a lecturer at UNS. He is a member of the Peruvian College of Biologists and was recognized by the World Aquaculture Society (WAS) in 2016 for his contribution to aquaculture.