Aquaculture is an established and critical part of the global food system, essential for the food security and livelihoods of millions. However, as it grows, it also faces constant scrutiny. Criticisms often resurface, questioning its sustainability, especially regarding its dependence on wild fisheries for feed.

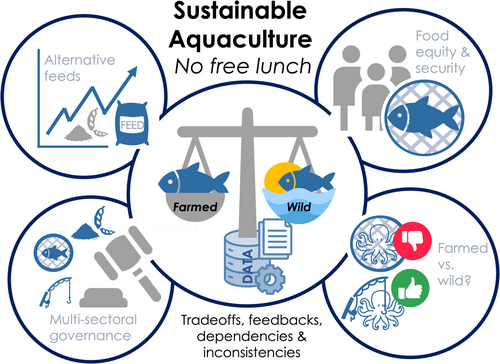

A recent opinion article published in Reviews in Aquaculture by a collective of leading scientists, led by Halley E. Froehlich of the University of California, argues that many of these debates ignore or minimize decades of scientific advances. The article, titled “No Free Lunch,” urges future research to build upon past progress rather than dismissing it.

This analysis breaks down the four main themes the authors address to refocus the debate on aquaculture sustainability, based exclusively on their findings.

- 1 Key takeaways

- 2 The central debate: Feed and fisheries

- 3 Recalculating FIFO: Why Old Data Fails

- 4 A problem of fisheries governance, not aquaculture

- 5 Aquaculture and food security

- 6 The moral dilemma: Who decides what is ethical?

- 7 The path toward “More data”

- 8 Conclusion: No free lunch

- 9 Entradas relacionadas:

Key takeaways

- The aquaculture sector has significantly reduced its impact and dependence on wild fish thanks to decades of scientific advances in feed efficiency (FCR) and ingredient substitution.

- Criticisms regarding FIFO are outdated: Many arguments about “fish in: fish out” (FIFO) are based on data from over 20 years ago and do not reflect current efficiencies.

- Including byproducts (trimmings) in feed is a key advance toward a circular economy and should not be counted as a penalty in sustainability calculations.

- The sustainability of forage fish depends on fisheries management, not aquaculture. If aquaculture stopped using them, other sectors (livestock, pets) would likely absorb that demand.

- There is no “free lunch”: All food production has an environmental impact. The goal must be comparative evaluation and continuous improvement, not the pursuit of an impossible zero impact.

The central debate: Feed and fisheries

The most direct interaction between aquaculture and wild fisheries is feed. For decades, the sector has been criticized for the paradox of “feeding fish with fish.” However, the authors argue that this criticism no longer reflects the sector’s reality.

The evolution of feed

As aquaculture expanded, the composition of its feed has changed drastically. It has shifted from a high dependency on fishmeal and fish oil (marine ingredients) to more cost-effective alternatives, primarily terrestrial crops like soy.

This change is not without criticism, as terrestrial crops require water and land and can contribute to deforestation. Nonetheless, the authors note that aquaculture’s impact in this regard is comparatively minor compared to its use in livestock and poultry farming.

The “Myth” of forage fish collapse

Although aquaculture (especially for fed species) has been the primary consumer of forage fish since the 2000s, this has not resulted in a widespread collapse of these fisheries. Forage fish landings have remained relatively stable over the last 40 years.

How is this possible? The authors attribute it to four key factors:

- Improvements in feed efficiency (better FCRs).

- A market shift: Fishmeal previously allocated to livestock (pigs, poultry) was reassigned to aquaculture.

- The shift toward more plant-based resources in diets.

- Increased incorporation of byproducts (trimmings) from the fish processing industry.

Recalculating FIFO: Why Old Data Fails

One of the most persistent criticisms is based on the “fish in: fish out” (FIFO) ratio. However, the article points out that many recent critical studies use extreme estimates based on data collected in the early 2000s, when efficiencies were much lower and fishmeal inclusion was higher.

Stay Always Informed

Join our communities to instantly receive the most important news, reports, and analysis from the aquaculture industry.

The authors strongly criticize that some recent calculations penalize aquaculture for using byproducts (trimmings), arguing this is “counterproductive.” Using parts of fish that humans do not consume (which account for 40% of fishmeal and oil production) is a positive advance toward a circular economy and a solution that reduces pressure on wild fisheries.

A problem of fisheries governance, not aquaculture

The authors insist that forage fish can be harvested sustainably if the proper fisheries management tools are used. The sustainability of these fisheries is a fisheries governance challenge, not an aquaculture management problem.

The reality is that fishmeal supply chains existed long before modern aquaculture. If aquaculture ceased its demand for fishmeal and fish oil, likely, other sectors (livestock, pets, pharmaceuticals) would simply absorb that supply.

Aquaculture and food security

Ignoring aquaculture’s contribution to food security is “myopic.” The sector contributes in two ways:

- Directly: By supplying nutritious food. Most aquaculture production (93% of freshwater and 80% of marine) is retained for national consumption.

- Indirectly: By supporting local incomes and employment.

The “food vs. feed” debate (using forage fish for direct human consumption instead of feed) is complex and context-dependent. For example, the authors note there is no evidence that the South American market could absorb the entirety of Peruvian anchoveta landings for direct human consumption. However, in West Africa, the capture of sardinella for feed is a growing concern, as it is a traditionally important food source for poor populations.

The moral dilemma: Who decides what is ethical?

Food production also involves moral questions, such as animal welfare and the perception of pain in fish and invertebrates.

The authors address the case of octopus farming, a practice that has led to preemptive bans in some regions (like California and Washington, USA) due to the recognized intelligence of these animals.

However, they point out a contradiction: These bans apply in regions where consumption is already low and do nothing to address wild capture. For example, the California law banning octopus farming still allows for 35 wild octopus to be fished per person, per day.

The conclusion is that avoiding all aquaculture for the sake of wild fish must be weighed against the “moral imperative” of improving nutrition and livelihoods for low-income people.

The path toward “More data”

All actors in the debate agree that higher-quality data is needed to assess social and environmental impacts. Aquaculture, in general, has more data limitations than agriculture or capture fisheries.

However, the authors argue that the issue is not if we need more data, but how to obtain it—something often overlooked. It is not enough to “simply demand more data.”

The true path to improving data collection lies in governance: better funding and government support, transparency mandates in supply chains (such as certification programs), and a collaborative, transdisciplinary approach.

Conclusion: No free lunch

The article by Froehlich et al. concludes with a fundamental reminder: “There is no free lunch.” All food production, including aquaculture, will have an environmental impact.

Aquaculture has made significant progress in reducing its impacts, backed by decades of science. The authors urge the scientific community and critics to build upon that research base, recognizing the complexity of a system that spans aquatic and terrestrial spaces.

Ignoring scientific advancements and the influence of fisheries and agricultural management on aquaculture sustainability only oversimplifies the problem. The goal must be comparative evaluation and continuous improvement, recognizing that sustainability is always a moving target.

Contact

Halley E. Froehlich

Department of Ecology, Evolution, & Marine Biology, University of California

Santa Barbara, California, USA

Email: hefroehlich@ucsb.edu

Reference (open access)

Froehlich, H. E., Gephart, J. A., Clawson, G., Blanchard, J. L., Essington, T. E., Golden, C. D., Halpern, B. S., Hardy, R. W., Naylor, R. L., & Troell, M. (2026). No Free Lunch: Sustainable Aquaculture Requires Recognizing Past Science, Improvements, and Comparative Assessment. Reviews in Aquaculture, 18(1), e70098. https://doi.org/10.1111/raq.70098

Editor at the digital magazine AquaHoy. He holds a degree in Aquaculture Biology from the National University of Santa (UNS) and a Master’s degree in Science and Innovation Management from the Polytechnic University of Valencia, with postgraduate diplomas in Business Innovation and Innovation Management. He possesses extensive experience in the aquaculture and fisheries sector, having led the Fisheries Innovation Unit of the National Program for Innovation in Fisheries and Aquaculture (PNIPA). He has served as a senior consultant in technology watch, an innovation project formulator and advisor, and a lecturer at UNS. He is a member of the Peruvian College of Biologists and was recognized by the World Aquaculture Society (WAS) in 2016 for his contribution to aquaculture.