Over the past decade, environmental DNA (eDNA) has revolutionized biodiversity monitoring. By filtering a simple water sample, we can identify which species inhabit an ecosystem—from bacteria to vertebrates—even detecting cryptic, invasive, or endangered organisms. This tool has significantly enhanced fisheries assessment and biodiversity monitoring.

However, eDNA has a fundamental limitation: it tells us who is present, but very little about what they are doing. Inferring dynamic physiological activities, such as reproduction, stress, or health status, remains a challenge.

This is where environmental RNA (eRNA) is beginning to shift the paradigm. Unlike DNA, RNA is an indicator of real-time gene activity. A new study by scientists from The University of Tokyo explores how eRNA can be used specifically to infer one of the most crucial and difficult-to-observe behaviors in the aquatic environment: spawning.

Key conclusions

- Environmental DNA (eDNA) is excellent for knowing which species are present, but not for inferring their dynamic physiological activities, such as reproduction.

- Environmental RNA (eRNA) is emerging as a tool that can capture these dynamic biological activities, as RNA is tissue-specific (like gametes or mucus) and reflects the organism’s functional state.

- The study identified the testis-specific gene klhl10 as a sensitive eRNA marker. Its levels in the water increased significantly only when fish mating occurred.

- A direct positive correlation was found between the duration of (video-recorded) mating attempts and the increase in klhl10 levels in the water, validating its use to infer spawning.

- This technique benefits aquaculture (reproductive monitoring), environmental assessment, and conservation, especially for locating the spawning grounds of hard-to-observe pelagic species.

Why environmental RNA (eRNA)?

Whereas eDNA is relatively stable, RNA is more dynamic and, crucially, is tissue-specific in multicellular organisms. In fish, the primary sources of eRNA in the water come from epithelial mucus (skin and gills) and gametes (sperm and eggs) released during reproduction.

The major challenge for fisheries managers has been locating the natural spawning grounds of key pelagic species, such as sardines and anchovies, whose stocks fluctuate enormously. If large quantities of gametes are released into the environment during spawning, eRNA markers specific to those gametes should increase dramatically in the water, acting as a scientific “beacon” indicating that spawning is occurring.

Searching for the perfect markers

To test this hypothesis, the researchers needed to find the correct genes. They used medaka (a model fish species) because their reproductive behavior is well-known: they spawn daily in the morning under specific conditions.

The team looked for two types of markers:

- A spawning marker: A gene expressed exclusively in the gonads (testes or ovaries).

- A control (epithelial) marker: A gene constantly expressed in the skin or gills, to confirm the presence of fish regardless of spawning.

After analyzing literature and transcriptomics data, they selected two main candidates:

- Spawning marker: klhl10. This gene proved to be highly specific to the testes, involved in spermatid formation.

- Control marker: muc5ac. This mucin gene is expressed in the skin and gills, but not in the gonads, serving as an epithelial indicator.

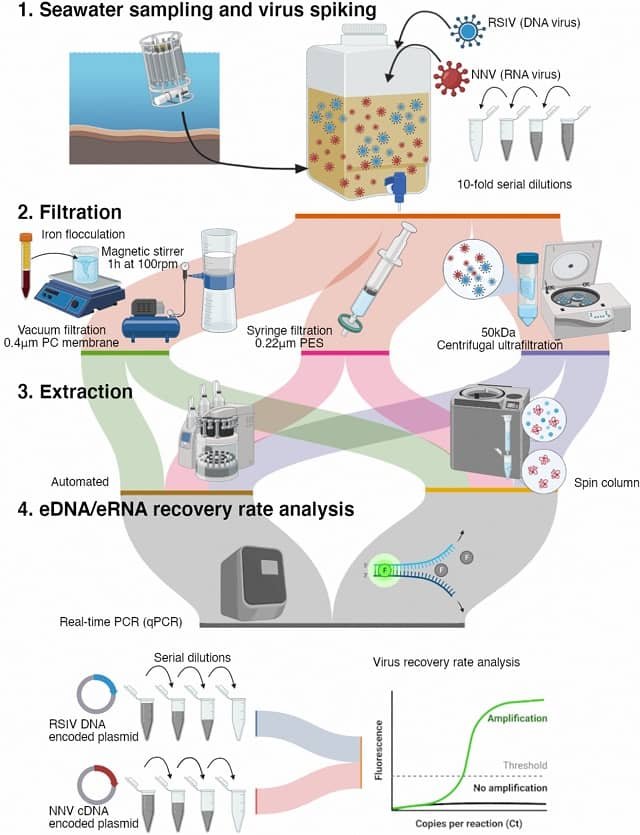

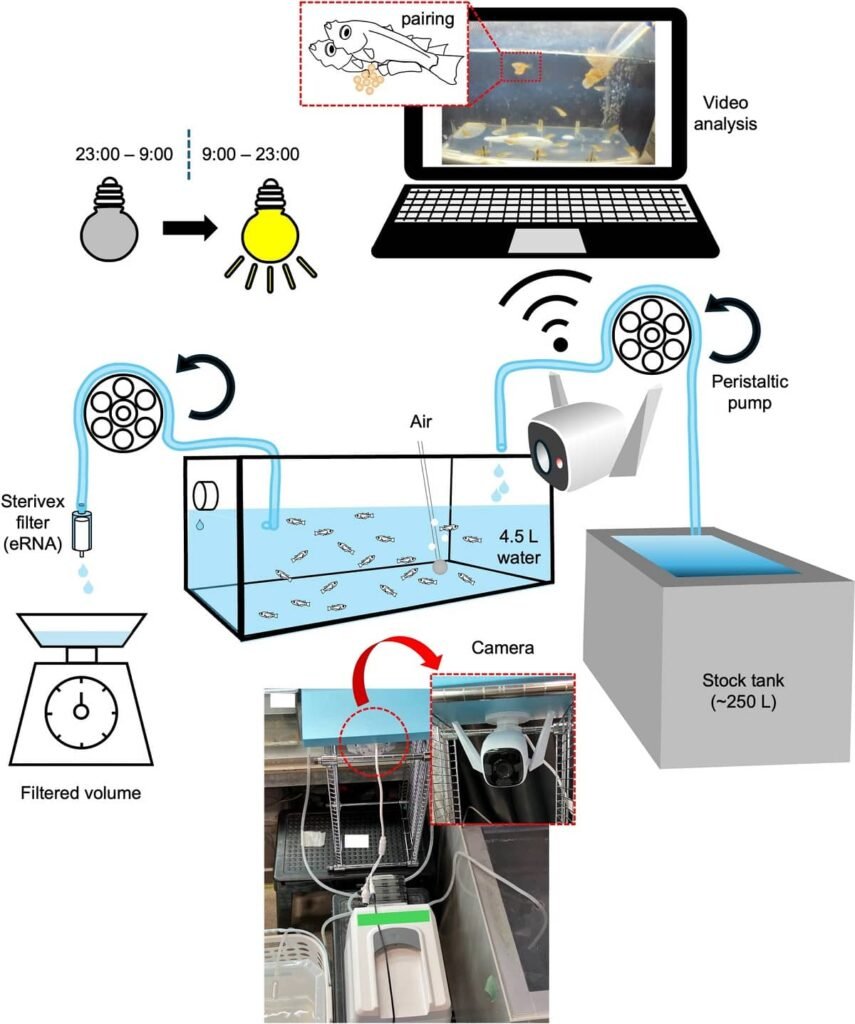

The experiment was straightforward: they placed different combinations of medaka in tanks (males only, females only, and mixed pairs). They then filtered the water from the tanks where mating was observed and from those where it was not, measuring the eRNA levels of klhl10 and muc5ac using qPCR.

Stay Always Informed

Join our communities to instantly receive the most important news, reports, and analysis from the aquaculture industry.

A direct correlation between eRNA and behavior

The results were clear and compelling, demonstrating that eRNA is a sensitive indicator of reproductive activity.

The klhl10 marker only appears during mating

The most important finding was that levels of the klhl10 spawning marker were significantly higher in the water from tanks where medaka pairs mated.

Conversely, in tanks containing only males, only females, or pairs that did not mate, klhl10 levels were mostly undetectable (see Figure 2A of the study). This confirms that the presence of this eRNA in the water is directly caused by the release of gametes during mating.

The muc5ac marker is constant

In contrast, the epithelial control marker muc5ac (mucus) was detectable in all water samples where fish were present. This was expected, as fish constantly shed mucus.

Crucially, muc5ac levels showed no differences between the groups that mated and those that did not. This demonstrates that the act of mating does not increase the release of epithelial mucus, reinforcing that klhl10 is a specific marker for spawning and not for a general increase in activity.

Video validation: eRNA matches behavior

To confirm the temporal relationship, the team conducted a more detailed experiment. They used an “isolated tank” and continuously recorded the fish’s behavior with an infrared camera, while taking water samples every hour.

The data showed that the increase in klhl10 transcripts in the water coincided perfectly with the duration of the mating attempts observed on video. A Pearson correlation analysis confirmed a significant positive correlation (r = 0.4776; p < 0.001) between mating duration and klhl10 levels.

Furthermore, eRNA proved to be a “real-time” indicator. klhl10 levels were only detectable in the morning (when medaka spawn) and were undetectable for the rest of the day. This is because RNA degrades rapidly in water (the study estimated the half-life of muc5ac at just 15 minutes at 25°C), which is an advantage: it ensures the detected signal corresponds to a recent event.

Implications for aquaculture and fisheries management

The findings of this study have direct practical applications for the sector. The development of a qPCR-based, sensitive, and specific eRNA marker for spawning is highly valuable for fieldwork.

- Fisheries Management: The main application is locating the spawning grounds of pelagic species. It is currently debated where species like mackerel or Pacific saury spawn. While eDNA can only track the migration of these fish, the addition of eRNA evidence (like klhl10) could provide a conclusive picture of where and when they are spawning. This technology is relatively low-cost, and results can be obtained within hours, even aboard research vessels.

- Aquaculture: eRNA monitoring can directly benefit aquaculture. Instead of invasive methods or direct observation, which can stress the broodstock, producers could take water samples from breeder tanks to non-invasively confirm the success and timing of spawning.

- Environmental Assessment and Conservation: This tool allows for the monitoring of species’ physiological activities in the field. Besides spawning, researchers suggest that other eRNA markers (like muc5ac) could be investigated as indicators of stress, disease, or activity levels in fish.

Conclusion

This study closes a critical gap that eDNA could not cover. By moving from simply identifying a species’ presence to detecting its dynamic physiological activities, environmental RNA offers a much richer view of what is happening underwater.

The identification of klhl10 as a sensitive and specific eRNA marker for spawning provides a powerful and practical tool. It allows scientists and managers to “listen in” on the molecular conversations of fish reproduction, an advancement that will undoubtedly benefit the sustainability of aquaculture, environmental assessment, and marine biodiversity conservation.

Contact

Marty Kwok-Shing Wong

Laboratory of Physiology, Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute, The University of Tokyo

5-1-5 Kashiwanoha, Kashiwa City, 277-8564, Chiba, Japan

Email: martywong@aori.u-tokyo.ac.jp

Reference (open access)

Aminaka, Y., Wong, M. K., Yada, T., & Hyodo, S. (2025). The use of environmental RNA for inferring fish spawning behavior. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23861-8

Editor at the digital magazine AquaHoy. He holds a degree in Aquaculture Biology from the National University of Santa (UNS) and a Master’s degree in Science and Innovation Management from the Polytechnic University of Valencia, with postgraduate diplomas in Business Innovation and Innovation Management. He possesses extensive experience in the aquaculture and fisheries sector, having led the Fisheries Innovation Unit of the National Program for Innovation in Fisheries and Aquaculture (PNIPA). He has served as a senior consultant in technology watch, an innovation project formulator and advisor, and a lecturer at UNS. He is a member of the Peruvian College of Biologists and was recognized by the World Aquaculture Society (WAS) in 2016 for his contribution to aquaculture.