Dominic McAfee, University of Adelaide; Chris Gillies, James Cook University; Christine Crawford, University of Tasmania; Ian McLeod, James Cook University, and Sean Connell, University of Adelaide

Australia once had vast oyster and mussel reefs, which anchored marine ecosystems and provided a key food source for coastal First Nations people. But after colonisation, Europeans harvested them for their meat and shells and pushed oyster and mussel reefs almost to extinction. Because the damage was done early – and largely underwater – the destruction of these reefs was all but forgotten.

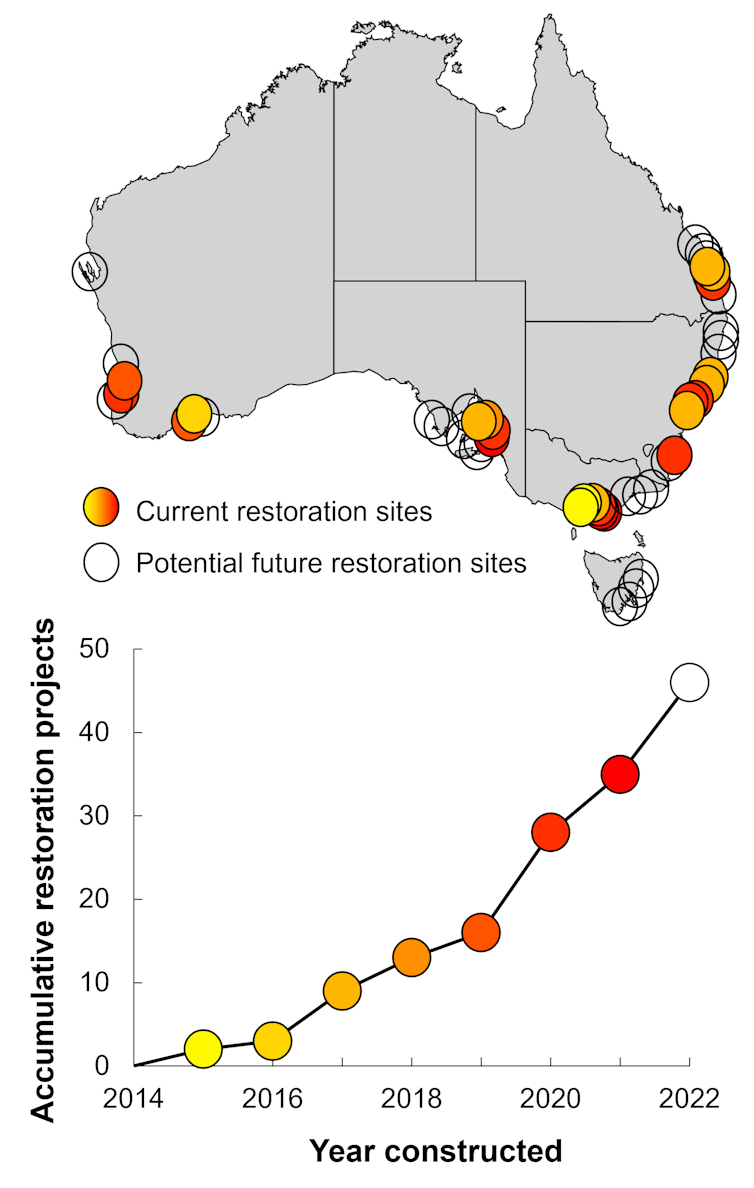

No longer. We have learned how to restore these vital reef systems. After a successful pilot in 2015, there are now 46 shellfish reef restorations underway – Australia’s largest marine restoration program ever undertaken. It’s not a moment too soon. There’s just one natural reef remaining for the Australian flat oyster, which is teetering on extinction.

How did shellfish reefs go from forgotten to frontline? Our new research shows how this historical amnesia was overcome through a national community of researchers, conservationists, and government and fisheries managers.

This matters, because oysters and mussels are ecological superheroes. As we restore these reefs, we give local marine life a real boost and support human livelihoods reliant on healthy seas. These cold-water reefs play a similar role to coral in tropical seas. They give hiding places and food to baby fish, filter seawater and defend coastlines against erosion from waves.

What killed our original shellfish reefs?

Just 200 years ago, shellfish reefs carpeted Australia’s temperate regions, filling up sheltered bays and estuaries around over 7,000 kilometres of coastline.

Archaeological research from Queensland shows First Nations people were sustainably harvesting local shellfish reefs over at least 5,000 years, replenishing oyster populations by building reefs with stone and shell.

This ended as Europeans took the lands and waters from Traditional Owners. Shellfish became one of colonial Australia’s first fisheries. Oysters were fished extensively for food, while their shells were burnt to manufacture lime for fertiliser and cement. If you walk past a colonial-era building, look at the mortar. Chances are, a lot of oyster shells went into it.

Even though the wild fishery ended a century ago, these shellfish weren’t able to return. That’s because they can’t just grow on bare sand. Their preferred substrate is the shells of their ancestors, left behind on the sea bottom. Once substrate was scraped by dredge or smothered by sediment, there was nowhere for baby oysters and mussels to settle and grow.

Stay Always Informed

Join our communities to instantly receive the most important news, reports, and analysis from the aquaculture industry.

Today, there’s just one small natural flat oyster reef (Ostrea angasi) and six remnant Sydney Rock oyster (Saccostrea glomerata) reefs remaining, across all Australian waters.

How to kick-start shellfish reef restoration

Shellfish can’t recover by themselves. But it turns out with a little human help, they can. Think of it as making up for our unsustainable use.

For a decade before the first large-scale restoration, recreational fishing groups and community groups worked on smaller projects, sometimes with government backing.

To begin larger-scale restoration work, we first had to remember how it used to be. Because the ecological collapse of Australia’s shellfish reefs was so profound, they were almost lost to human memory. Historical records guided us as to what a restored ecosystem should look like, and where these reefs used to be.

Our job was made easier because of the huge benefits shellfish reefs provide to marine life. Intact oyster and mussel reefs are natural fish factories providing nursery habitats for economically important fish species like bream and whiting.

Even better, these filter-feeding shellfish are the kidneys of the coast, cleaning water cloudy with sediment or overloaded with nutrients. A single oyster can filter 100 litres of water a day. Shellfish reefs also act as living defences against the energy of waves, store carbon in their shells and help protect intertidal communities from the warming climate through shade and moisture at low tide.

People working on reef restoration turned to our thriving oyster and mussel farming industry to understand their life cycles and what they needed to thrive. The fact these farms are successful indicated many areas remained suitable for shellfish reefs.

Environmental NGO The Nature Conservancy connected the emerging reef restoration community as well as bringing practical experience from longer-running shellfish restoration projects in America. Reef restoration work is now being led by conservation NGOs, local and state governments, and, increasingly, by community groups.

So does it work? Yes. It’s as if the oysters have been waiting for this opportunity. Many human-made reefs have been settled by millions of baby oysters within months of construction, such as the largest project to date, the 20 hectare Windara Reef in South Australia. Some restored reefs are closing in on oyster densities in line with natural reefs.

Looking forward

We hope the rapid rise of shellfish reef restoration is the beginning of a new era for large-scale marine restoration in Australia.

Today, community-led restorations are growing in scale and number, and public support for shellfish restoration is widespread.

It is an impressive story. This is a national program of recovery showing significant successes with a relatively modest investment. These restoration efforts show large-scale action to repair nature can work – and work quickly – when experts from a range of disciplines work with communities towards a common goal.

As the restored oyster and mussel reefs mature, we will see more fish in our seas and more recreation and tourism opportunities emerging. That, in turn, could give more communities the idea to restore their own shellfish reefs. Together, we can bring back the reefs which lived in our cooler seas for millennia.

Dominic McAfee, Postdoctoral researcher, marine ecology, University of Adelaide; Chris Gillies, Adjunct Associate Professor in marine ecology, James Cook University; Christine Crawford, Senior research fellow in marine biology, University of Tasmania; Ian McLeod, Professorial Research Fellow in Marine Biology, James Cook University, and Sean Connell, Professor, Program Director of Stretton Institute, Program Director of Environment Insitute, University of Adelaide

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Editor at the digital magazine AquaHoy. He holds a degree in Aquaculture Biology from the National University of Santa (UNS) and a Master’s degree in Science and Innovation Management from the Polytechnic University of Valencia, with postgraduate diplomas in Business Innovation and Innovation Management. He possesses extensive experience in the aquaculture and fisheries sector, having led the Fisheries Innovation Unit of the National Program for Innovation in Fisheries and Aquaculture (PNIPA). He has served as a senior consultant in technology watch, an innovation project formulator and advisor, and a lecturer at UNS. He is a member of the Peruvian College of Biologists and was recognized by the World Aquaculture Society (WAS) in 2016 for his contribution to aquaculture.