Garth A Covernton, University of Toronto; Hailey Davies, University of Victoria, and Kieran Cox, University of Victoria

Microplastics — tiny pieces of plastic less than five millimetres in size — have been found in marine and freshwater animals ranging from tiny zooplankton to large whales.

Scientists have found that microplastics have the potential to cause harm to animals through pathways including replacing food and leaching added chemicals into their bodies. However, it’s unclear how much these effects are currently occurring in the environment.

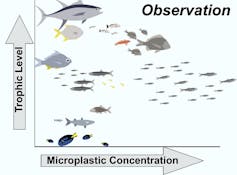

Our recently published study explores how microplastics move within coastal marine food webs. We found that smaller animals feeding lower in the food web might be at greater risk from microplastic exposure than larger predatory animals.

Pollutants and food webs

Food webs are tangled networks of organisms feeding on each other. Where an animal is feeding within this tangled network is called its trophic position and may determine its exposure to pollutants.

For example, mercury pollution accumulates in the muscles of animals and is passed from prey to predators, reaching higher levels of concentration through the food web.

This process is called biomagnification, and it’s why animals like tuna and salmon end up with potentially dangerous concentrations of pollutants.

Do microplastics biomagnify?

During the summer of 2018, we collected individuals — including clams, mussels, sea cucumbers, crabs, sea stars and fishes — across a food web from several sites around southern Vancouver Island.

Stay Always Informed

Join our communities to instantly receive the most important news, reports, and analysis from the aquaculture industry.

We then determined the concentrations of microplastics found in the guts of the animals and the liver of the fishes and related these concentrations to each animal’s place in the food web.

Animals higher in the food web did not contain greater concentrations of microplastics than animals lower in the food web, suggesting that biomagnification was not occurring.

Some of our past work has also shown a lack of evidence for biomagnification of microplastics. In that work, we compared microplastic concentrations in fish guts, reported in the scientific literature, with estimates of their place within food webs.

Some species might be at greater risk

Although we didn’t find evidence of biomagnification, we did find that concentrations of microplastics were higher for certain smaller species when compared to their body weight.

This included filter feeding animals like clams, mussels and certain sea cucumbers, as well as a type of fish, the shiner surfperch. These fish might be ingesting more microplastics because the particles are similar in size and shape to their preferred food — small aquatic microorganisms like zooplankton and other small invertebrates.

However, the numbers of microplastics we found in all animals were less than two particles per individual on average. While this could mean that health risks to these animals are low, we have yet to understand how long-term exposure to low concentrations of microplastics could affect their health.

In our research, we were limited to studying particles greater than 100 microns in size — about the width of a human hair — as particles smaller than this are very difficult to study using a regular microscope. However, emerging methods may make them easier to investigate in the future. These smaller particles are potentially more toxic and we can’t rule out biomagnification at this scale, even if it’s not occurring for larger particles.

How are microplastics affecting aquatic food webs?

As microplastics pollution of the environment increases, we need to understand its possible effects to avoid potential ecosystem disasters in the future.

Freshwater ecosystems, for example, are often more directly exposed to microplastics and can contain higher concentrations.

Researchers, including a member of our team, are currently conducting work at the International Institute for Sustainable Development’s Experimental Lakes Area to help understand how microplastics exposure might affect freshwater ecosystems and food webs.

This work, alongside the work of other researchers, should advance our understanding of how microplastics can affect aquatic ecosystems, especially the effects on the small animals at the base of food webs that might be ingesting more of these particles.

Garth A Covernton, Postdoctoral fellow, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Toronto; Hailey Davies, PhD Student, Department of Biology, University of Victoria, and Kieran Cox, Postdoctoral fellow, Marine Ecology, University of Victoria

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Editor at the digital magazine AquaHoy. He holds a degree in Aquaculture Biology from the National University of Santa (UNS) and a Master’s degree in Science and Innovation Management from the Polytechnic University of Valencia, with postgraduate diplomas in Business Innovation and Innovation Management. He possesses extensive experience in the aquaculture and fisheries sector, having led the Fisheries Innovation Unit of the National Program for Innovation in Fisheries and Aquaculture (PNIPA). He has served as a senior consultant in technology watch, an innovation project formulator and advisor, and a lecturer at UNS. He is a member of the Peruvian College of Biologists and was recognized by the World Aquaculture Society (WAS) in 2016 for his contribution to aquaculture.