The aquaculture of mollusks (oysters, abalones, mussels) and crustaceans (shrimp, prawns, crabs) is a cornerstone of global food security; in 2022, its production surpassed wild-capture fisheries with over 94 million tonnes. However, the intensification of these farming practices has triggered a “perfect storm” of viral and bacterial diseases that threaten the sector’s sustainability.

Researchers from La Trobe University (Australia) have published an exhaustive review in the journal Pathogens that challenges the current paradigm of disease control. Given that invertebrates possess only innate immunity, strategies must focus on enhancing these natural defenses through immunological priming and the use of next-generation immunostimulants.

Key Highlights

- Moving Beyond Traditional Vaccines: Invertebrates lack adaptive immunity (antibodies), rendering conventional fish vaccines ineffective for these species.

- Immunological Priming: It is possible to “train” the innate system of these animals to respond more efficiently to pathogens following a prior exposure.

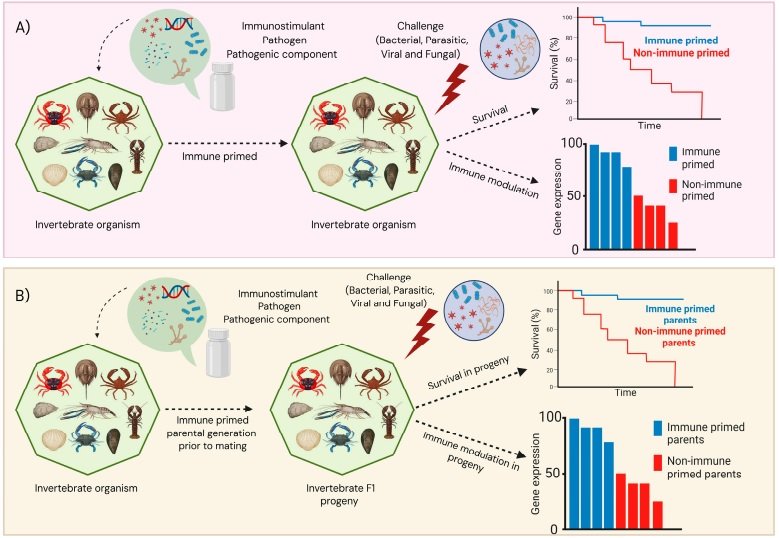

- Hereditary Protection: Transgenerational Immune Priming (TGIP) allows parents to transfer resistance to their offspring, protecting them during their most critical larval stages.

- Precision Immunostimulants: The use of molecules such as dsRNA, beta-glucans, and viral proteins (VP28) offers survival rates of up to 100% under controlled conditions.

The Arsenal of Innate Immunity: How Do They Defend Themselves?

Unlike humans or fish, invertebrates do not produce specific antibodies after an infection. Their defense is divided into two main fronts:

- Cellular Defense: Mediated by hemocytes that eliminate pathogens through phagocytosis (ingestion of the invader), encapsulation, and the production of superoxides.

- Humoral Defense: Based on processes such as melanization (activated by the pro-phenoloxidase or proPO enzyme), hemolymph agglutination, and the secretion of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs).

The complexity of their receptors is striking. While vertebrates possess between 10 and 15 families of Toll-like receptors (TLRs), species such as the Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) have up to 83 genes encoding these receptors, suggesting massive evolutionary specialization to detect environmental threats.

Priming and Transgenerational Immunity: The Memory of the Innate System

The concept of immunological priming refers to an enhanced defensive response following prior exposure to a pathogen or pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP). For it to be considered true priming, the animal must exhibit higher survival rates and a lower pathogen load upon a secondary challenge.

The Generational Leap (TGIP)

One of the most disruptive discoveries is Transgenerational Immune Priming (TGIP). In crustaceans like the black tiger prawn (Penaeus monodon), maternal exposure to fungal beta-glucans improved offspring resistance to the devastating White Spot Syndrome Virus (WSSV). In mollusks, it has been demonstrated that parents treated with Poly(I:C)—a viral mimic—produce larvae with significantly lower viral DNA loads and reduced mortality against the Ostreid herpesvirus (OsHV-1).

The Main Players: Key Immunostimulants

The review identifies several molecules with prophylactic potential, classified by their composition:

- Nucleic Acids (dsRNA and CpG): dsRNA (double-stranded RNA) is a potent viral mimic that activates pathways similar to the interferon response in vertebrates. The use of Poly(I:C) has achieved near-total protection (100% survival) in oysters against OsHV-1, maintaining active immunity for up to 156 days in field conditions. Additionally, CpG ODNs (bacterial DNA motifs) have been shown to reduce mortality in the Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis) against bacteria like Aeromonas hydrophila.

- Structural Proteins (The VP28 Case): In the fight against WSSV in shrimp, viral capsid proteins—particularly VP28—have been the most widely studied. Oral administration of VP28 encapsulated in Bacillus subtilis spores or expressed in microalgae (such as Chlamydomonas reinhardtii) offers survival rates between 70% and 94%, providing a cost-effective and scalable alternative to injection.

- Carbohydrates (Beta-glucans and Peptidoglycans): Beta-glucans (derived from yeast and fungi) are the most commercially utilized immunostimulants. Although their efficacy varies by structure and dosage, they have been proven to increase phenoloxidase activity and phagocytosis across multiple species. Peptidoglycans (PGN) have achieved long-term protection in the Kuruma prawn (Penaeus japonicus), reaching survival rates of 90–100%.

Challenges for Industrial Implementation

Despite laboratory success, the transition to commercial farms faces critical hurdles:

- Toxicity and Therapeutic Window: Certain stimulants, such as bacterial flagellin (FlaA), become toxic if recommended doses are exceeded, causing mortality instead of protection.

- Fitness Costs: Maintaining an immune system in a state of constant high alert consumes metabolic energy. In the Peruvian scallop (Argopecten purpuratus), there is a clear trade-off: when investing in defense after a bacterial attack, reproductive capacity decreases drastically.

- Administration Logistics: While injection is the most precise method, it is unfeasible at scale. The future lies in dietary encapsulation or the use of biological carriers like transgenic algae.

Conclusion and Future Outlook

Redesigning disease control in invertebrate aquaculture requires understanding that innate immunity is neither “simple” nor lacking in memory. The strategic use of immunostimulants that trigger priming and TGIP offers a sustainable, antibiotic-free pathway to protect the most vulnerable species.

Stay Always Informed

Join our communities to instantly receive the most important news, reports, and analysis from the aquaculture industry.

Contact

Karla Helbig

Department of Microbiology, Anatomy, Physiology & Pharmacology, La Trobe University.

Bundoora, VIC 3083, Australia

Email: k.helbig@latrobe.edu.au

Reference (open access)

Ackerly, D., Agius, J., Beveridge, D., Helbig, K., & Beddoe, T. (2026). Rethinking Disease Control in Aquaculture Invertebrates: Harnessing Innate Immunity in Molluscs and Crustaceans. Pathogens, 15(168), 1-55. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15020168

Editor at the digital magazine AquaHoy. He holds a degree in Aquaculture Biology from the National University of Santa (UNS) and a Master’s degree in Science and Innovation Management from the Polytechnic University of Valencia, with postgraduate diplomas in Business Innovation and Innovation Management. He possesses extensive experience in the aquaculture and fisheries sector, having led the Fisheries Innovation Unit of the National Program for Innovation in Fisheries and Aquaculture (PNIPA). He has served as a senior consultant in technology watch, an innovation project formulator and advisor, and a lecturer at UNS. He is a member of the Peruvian College of Biologists and was recognized by the World Aquaculture Society (WAS) in 2016 for his contribution to aquaculture.