Genetic diversity is not merely an academic concept; it serves as the ‘instruction manual’ that enables a species to adapt, evolve, and survive the threats of climate change, disease, and anthropogenic pressure. For humanity, this diversity constitutes the cornerstone of food security.

Nevertheless, as the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) warns, this biological wealth is under an unprecedented threat. While domestication and genetic improvement have optimized production, they have also created bottlenecks that jeopardize long-term sustainability. In this context, the establishment of gene banks emerges not simply as an option but as an indispensable tool for resource management.

Key Points

- Biological Life Insurance: Cryopreservation is the fundamental tool for safeguarding aquatic genetic diversity against the climate crisis and overfishing.

- Standardization Gap: Unlike terrestrial livestock, the in vitro conservation of aquatic species still lacks unified global protocols.

- Beyond Sperm: New frontiers include the preservation of germ cells and algal tissues to reconstitute entire populations.

- Imperative Legal Framework: The success of biobanks strictly depends on compliance with Access and Benefit-Sharing (ABS) laws and the Nagoya Protocol.

What is Ex Situ In Vitro Conservation?

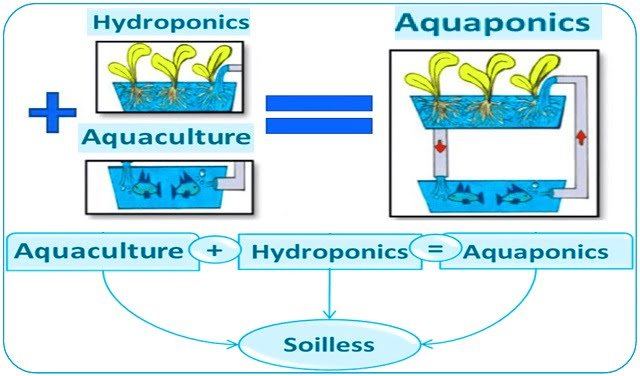

While in situ conservation protects animals within their natural habitats and live gene banks maintain captive populations, ex situ in vitro conservation involves extracting biological material (cells, tissues, or gametes) and maintaining it outside the organism. This is typically achieved through cryopreservation at extreme temperatures (liquid nitrogen at -196°C).

This approach functions as a critical backup system. If a wild population vanishes or an aquaculture farm suffers a disease-driven collapse, the material stored in these biobanks allows for the “restarting” of the system, thereby recovering lost genetic variability.

The Scientific Process: From Capture to Liquid Nitrogen

To understand how an aquatic gene bank operates, we can envision a carefully orchestrated process of “biological pause.” According to FAO guidelines, the workflow is categorized into “preservation pathway” levels.

Collection and the Challenge of Contamination

The initial step involves selecting healthy donors, whether wild-caught or sourced from aquaculture farms. Asepsis is critical: a single drop of water or mucus can prematurely trigger sperm motility or introduce bacteria that jeopardize the sample’s integrity.

The Biological “Antifreeze”: Cryoprotective Agents (CPAs)

If a cell were frozen directly, internal water would form jagged ice crystals that rupture cell membranes—much like a water pipe bursting in winter. This is where cryoprotectants, such as dimethyl sulfoxide ($DMSO$) or methanol, are utilized. These substances permeate the cell, displacing water and allowing the interior to become “vitreous” or glassy rather than crystalline.

The Freezing Curve

Success depends not on cooling rapidly, but on cooling with precision. Each species possesses an optimal cooling rate. If it is too slow, the cell suffers toxicity from high solute concentrations; if it is too fast, lethal intracellular ice crystals form.

Storage and Monitoring

Once -196°C is reached, samples are stored in liquid nitrogen tanks (dewars). In this stage, data management is as vital as the cold itself: a sample lacking information regarding its origin, species, or quality is biologically useless.

Stay Always Informed

Join our communities to instantly receive the most important news, reports, and analysis from the aquaculture industry.

The Challenge: Aquatic vs. Terrestrial Sectors

The FAO highlights a stark reality: compared to crop and livestock sectors, the in vitro conservation of aquatic species is significantly less developed. The challenges are multifaceted:

- Extreme Taxonomic Diversity: Freezing bull semen is fundamentally different from managing the complex physiology of thousands of species of fish, mollusks, or microalgae.

- Lack of Protocols: A deficiency in standardized methods and inconsistent terminology continues to hinder international collaboration.

- Transparency: Limited guidelines for reporting and notifying results impede the replicability of scientific breakthroughs.

A Strategic Manual for the Future of Food Security

The technical document presented by the FAO pursues an ambitious objective: to support policymakers, resource managers, aquaculture producers, and researchers in advancing these technologies. The guidelines encompass everything from technical specifications to regulatory frameworks.

Finfish

Fish sperm is relatively straightforward to cryopreserve due to its small size and simple structure. However, fish eggs (oocytes) and embryos have proven nearly impossible to successfully cryopreserve thus far, owing to their large volume, high lipid content, and low permeability.

To overcome this, centers like CEPTA/ICMBio in Brazil are focusing on the preservation of Primordial Germ Cells (PGCs). These cells can be transplanted into a sterile host that subsequently produces gametes of the donor species, enabling the full recovery of a population.

Shellfish

In bivalve mollusks such as the Pacific oyster (Magallana gigas), gene banks are already safeguarding industries. When outbreaks of the OsHV-1 herpesvirus decimated populations in France and New Zealand, sperm banks allowed breeders to select virus-resistant families to repopulate farms.

Algae

Microalgae and macroalgae are fundamental not only for food but also for biofuels and carbon sequestration. Algae culture centers utilize cryopreservation to prevent “genetic drift,” which occurs when strains are repeatedly subcultured in laboratory settings.

Organization and Costs

Establishing a gene bank involves more than purchasing nitrogen tanks. It requires a robust logistical infrastructure, highly trained personnel, and a long-term financial commitment. The FAO emphasizes that the cost of failing to conserve these resources far outweighs the investment required to protect them.

Regulatory Considerations

Access to these resources and the Access and Benefit-Sharing (ABS) derived from their use—based on the Nagoya Protocol—are essential for ensuring that conservation remains ethical and equitable among nations.

Global Impact

These guidelines are far from abstract theory; they are grounded in the extensive expertise of world-leading institutions.

- AGGRC (USA): The Aquatic Germplasm and Genetic Resources Center at Louisiana State University serves as a model for developing integrated repositories, adapting dairy industry techniques for aquaculture.

- Embrapa (Brazil): It manages one of the largest collections of Neotropical fish, including commercial species such as tambaqui (gamitana) and pirarucu (paiche).

- ICAR-NBFGR (India): This institution has developed protocols for 30 native species, producing over 11 million larvae from cryopreserved sperm on local farms.

- Cryogenetics (Norway): A private firm that demonstrates the commercial viability of cryopreservation services for the global salmon industry.

Tangible Benefits: Beyond Conservation

The broader implementation of these technologies would drastically enhance the management of Aquatic Genetic Resources (AqGR). For aquaculture producers, this translates to:

- Accelerated Selective Breeding: Maintaining varieties with rapid growth rates or disease resistance.

- Biosecurity: Establishing a safety net against natural disasters or viral outbreaks that could decimate an installation’s live stock.

- Ecosystem Restoration: Facilitating the reintroduction of native species into degraded habitats with a diverse genetic foundation.

Perspectives: The Path Forward

As the FAO highlights, progress in this field is vital. For this “Noah’s Ark” to be effective, we require greater international standardization and a steady flow of data between laboratories and governments. Integrating in vitro conservation with in situ efforts will create a more resilient biodiversity management system, capable of feeding a growing global population on a changing planet.

Reference (open access)

FAO. 2026. Aquaculture development – Guidelines for ex situ in vitro gene banking of aquatic genetic resources. FAO Technical Guidelines for Responsible Fisheries, No. 5 Suppl. 13. Rome. https://doi.org/10.4060/cd7559en

Editor at the digital magazine AquaHoy. He holds a degree in Aquaculture Biology from the National University of Santa (UNS) and a Master’s degree in Science and Innovation Management from the Polytechnic University of Valencia, with postgraduate diplomas in Business Innovation and Innovation Management. He possesses extensive experience in the aquaculture and fisheries sector, having led the Fisheries Innovation Unit of the National Program for Innovation in Fisheries and Aquaculture (PNIPA). He has served as a senior consultant in technology watch, an innovation project formulator and advisor, and a lecturer at UNS. He is a member of the Peruvian College of Biologists and was recognized by the World Aquaculture Society (WAS) in 2016 for his contribution to aquaculture.