William W. L. Cheung, University of British Columbia

Restaurant menus across the West Coast of Canada will soon see an influx of squid and sardine dishes, while the popular sockeye salmon makes a slow exit. As it turns out, climate change may have something to do with this.

Restaurants update their menus all the time and this often goes unnoticed by diners. These changes are driven by culinary trends, consumer preferences and many environmental and socio-economic factors that affect the availability of the ingredients. According to a recent study published by my research team, we can now add climate change to this list.

We found that as the ocean temperature rises, many marine fish and shellfish move from their traditional habitats towards the North and South Poles in search of cooler waters. This movement of fish stocks affects the availability of seafood catch, compelling chefs to rewrite the menus of seafood restaurants on the West Coast of Canada.

Climate change affects our ocean and fisheries

The latest report from the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change confirmed that climate change is impacting the ocean, fish stocks and fisheries through ocean warming, loss of sea ice, ocean acidification, heatwaves, ocean deoxygenation and other extreme weather events.

The impacts of warming-induced ecological shifts are also seen in our fisheries. Fish catches around the world are increasingly dominated by species that prefer warmer water.

We applied an index called “mean temperature of catch” to measure such changes in species of fish caught along the West Coast of Canada, and found that the catch of warmer-water species in this region has increased from 1961 to 2016.

But how exactly do these changes in fisheries catch dictate the food that appears in our plates? My co-author John-Paul Ng and I decided to tackle this question ourselves by focusing our efforts on the West Coast of Canada and the U.S. where many restaurants serve seafood.

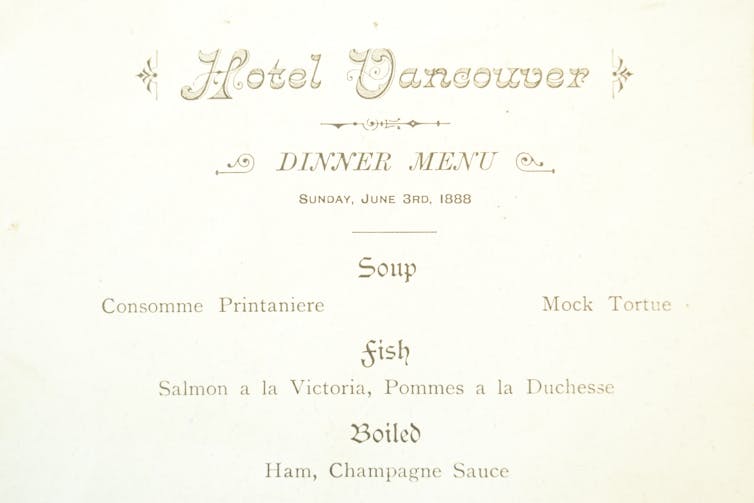

We looked at present-day menus from restaurants in these areas, along with menus — some dating back to the 19th century — taken from historical archives in city halls and local museums.

Stay Always Informed

Join our communities to instantly receive the most important news, reports, and analysis from the aquaculture industry.

After looking at 362 menus, we used a similar approach to the one we developed to study fisheries catches and calculated a “mean temperature of restaurant seafood.” This index represents the average preferred temperature across all seafood species that appeared on the sampled menus from restaurants in a city for a specific time period. This index is a tool to help us gauge whether our restaurants are serving more or less warm and cold water seafood.

We found that the average preferred water temperature of fish and shellfish appeared in our menu increased to 14 C in recent times (2019-21) from 9 C in 1961-90 period.

This increase in the preferred water temperature of fish on restaurant menus is connected to changes in sea water temperature and the temperature-related changes in the composition of fish species caught during the same time period.

More squid and sardine dishes

Ocean warming is starting to change the variety of seafood available.

Driven by the higher ocean temperature in the northeast Pacific Ocean, the Humboldt squid — a large, predatory squid species that inhabits the eastern Pacific Ocean — is now making more frequent appearances on present-day restaurant menus in Vancouver.

British Columbia once had a commercially important Pacific sardine fishery, which was a common restaurant seafood. After the fishery collapsed in the mid-1940s, the fish seldom appeared in our sampled restaurant menus.

According to research conducted by colleagues in fisheries research and by our team at the Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries, the sardines, which prefer warmer water, will soon make a big comeback on the West Coast of Canada. We expect that more sardine dishes will start appearing on the menus of restaurants here.

Responding to changing seafood availability

Globalization and the diversification of cuisines have brought a wider array of seafood options to coastal cities such as Vancouver and Los Angeles. Imported and farmed seafood are increasingly common ingredients in menus.

As climate change continues to shuffle species’ distribution in ocean waters, we expect that climate-induced changes to seafood menus at restaurants will become even more pronounced.

Our study on restaurant menus underscores the wide-ranging impacts of climate change on our food system. In cases where alternative seafood ingredients are available and consumer preferences are flexible, the impacts on our social, economic and cultural well-being may be limited. However, substantial negative consequences are likely to be felt by many vulnerable communities that do not have the capacity to adapt to such changes.

Global and local actions to support both climate change adaptation and mitigation are essential if we want the ocean to continue to provide food for the people around the world who rely on it for nutritional security.

William W. L. Cheung, Professor and Director, Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries, University of British Columbia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Editor at the digital magazine AquaHoy. He holds a degree in Aquaculture Biology from the National University of Santa (UNS) and a Master’s degree in Science and Innovation Management from the Polytechnic University of Valencia, with postgraduate diplomas in Business Innovation and Innovation Management. He possesses extensive experience in the aquaculture and fisheries sector, having led the Fisheries Innovation Unit of the National Program for Innovation in Fisheries and Aquaculture (PNIPA). He has served as a senior consultant in technology watch, an innovation project formulator and advisor, and a lecturer at UNS. He is a member of the Peruvian College of Biologists and was recognized by the World Aquaculture Society (WAS) in 2016 for his contribution to aquaculture.