Global seafood consumption has experienced exponential growth, driven by its exceptional nutritional value and gastronomic versatility. However, this surge brings a latent risk of food poisoning caused by marine biotoxins. While sanitary surveillance has traditionally focused on bivalve mollusks, a recent technical review warns that crustaceans and fish act as critical vectors often overlooked by current regulations. This study was conducted by researchers from the Department of Microbiology of Food and Feed at the National Veterinary Research Institute in Poland and published in the prestigious scientific journal Toxins in December 2025.

Key Study Findings

- Unregulated Vectors: Crustaceans (crabs, lobsters, and shrimp) and various fish accumulate toxins dangerous to humans, despite their exclusion from mandatory European Union monitoring.

- Environmental Factors: Climate change and coastal eutrophication are increasing the incidence of so-called “emerging toxins.”

- Thermal Resistance: Common processing and cooking methods do not always eliminate toxicity in contaminated products.

- Regulatory Gap: There is an urgent need to establish legal limits and standardized analytical methods for non-bivalve organisms.

- Sectoral Impact: Economic losses from fishery closures due to Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs) severely impact the sector’s sustainability.

The Impact of Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs)

Marine biotoxins, or phycotoxins, are primarily generated during massive phytoplankton growth, a phenomenon known as “red tides” or HABs. These events depend on critical environmental variables such as nutrient availability (nitrogen and phosphorus), water temperature, and CO2 concentration.

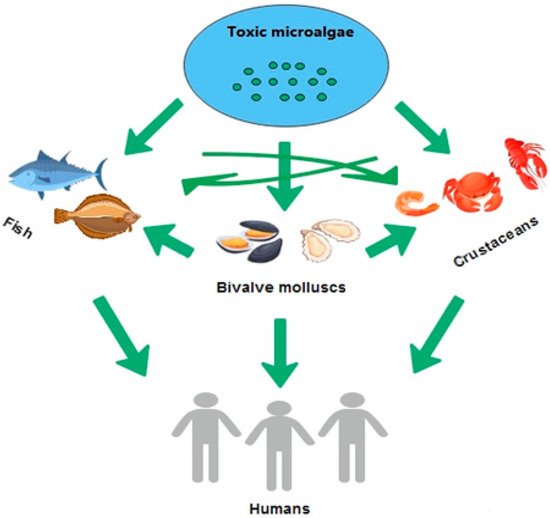

Of the 5,000 identified marine algae species, over 100 produce harmful toxins. While genera like Noctiluca only alter water coloration, algae from the genera Alexandrium, Dinophysis, and Pseudo-nitzschia are responsible for severe human poisoning. Aquatic organisms absorb these substances through feeding, accumulating them in various organs and tissues.

Crustaceans: Significant Vectors of Toxicity

As omnivorous organisms, crustaceans can ingest toxins directly from algae or by consuming contaminated prey, transferring the risk to higher levels of the trophic chain.

- Crabs and Okadaic Acid (DSP) Accumulation: Outbreaks of Diarrhetic Shellfish Poisoning (DSP) linked to the consumption of green crabs (Carcinus maenas) and brown crabs (Cancer pagurus) have been documented in Europe. In Portugal, levels of 320 µg/kg of okadaic acid were detected in edible parts of green crabs, while in Norway, brown crab samples revealed concentrations up to 1500 µg/kg in the hepatopancreas. Toxicity persists even after cooking, confirming that crabs are highly efficient indirect vectors.

- Lobsters and the Risk of Paralytic Toxins (PSP): Lobsters accumulate paralytic toxins after consuming contaminated bivalves. The species Jasus edwardsii can concentrate large amounts of saxitoxin in its liver and pancreas within days. Research in Canada reported levels up to 4470 µg STX eq./kg in the hepatopancreas of Homarus americanus. Notably, cooking does not reduce total toxicity, though it may alter the mass of the affected tissue.

The Role of Fish in the Trophic Chain

Fish accumulate biotoxins through three pathways: phytoplankton ingestion, absorption of dissolved toxins through the epithelium, or consumption of contaminated prey.

- Ciguatera (CFP): The most frequent seafood poisoning globally, associated with fish from tropical and subtropical regions, causing an estimated 50,000 to 200,000 cases annually.

- Tetrodotoxin (TTX): A potent neurotoxin that can be lethal to humans, with the highest concentrations typically found in the ovaries and liver.

- Pelagic Fish: Species such as sardines and anchovies act as vectors for domoic acid (ASP) during Pseudo-nitzschia blooms.

Challenges in Detection and Sanitary Monitoring

Industry and regulators face the challenge of identifying a growing variety of toxins in complex food matrices. Advanced chemical methods, such as High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS), are currently the most precise tools for quantification. Furthermore, the Mouse Bioassay (MBA) is being replaced due to ethical limitations and precision issues, although the lack of certified reference materials continues to hinder the development of official protocols for emerging toxins.

Economic and Regulatory Perspectives

According to the FAO, global fish consumption reached 20.2 kg per person in 2020, a trend expected to increase pressure on food safety systems. While Regulation (EC) No 853/2004 sets biotoxin limits for bivalves, no equivalent regulations exist for crustaceans and fish. This legal void must be addressed through the classification of production areas and specific sampling plans to ensure the sector’s safety through innovation and comprehensive risk assessment.

Reference (open access)

Madejska, A., & Osek, J. (2025). Marine Biotoxins in Crustaceans and Fish—A Review. Toxins, 17(12), 589. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120589

Editor at the digital magazine AquaHoy. He holds a degree in Aquaculture Biology from the National University of Santa (UNS) and a Master’s degree in Science and Innovation Management from the Polytechnic University of Valencia, with postgraduate diplomas in Business Innovation and Innovation Management. He possesses extensive experience in the aquaculture and fisheries sector, having led the Fisheries Innovation Unit of the National Program for Innovation in Fisheries and Aquaculture (PNIPA). He has served as a senior consultant in technology watch, an innovation project formulator and advisor, and a lecturer at UNS. He is a member of the Peruvian College of Biologists and was recognized by the World Aquaculture Society (WAS) in 2016 for his contribution to aquaculture.

Stay Always Informed

Join our communities to instantly receive the most important news, reports, and analysis from the aquaculture industry.