by Ivy Kupec, EMBL

Marine parasites invade single-celled microalgae, devouring the nucleus and hijacking metabolism while the organism remains alive.

It’s a tale as old as time. Parasite feeds on another species, taking what it needs and leaving a host-organism corpse in its wake.

One might think in the world of microalgae, this doesn’t even occur. Or that parasites there feast on an entire single-celled organism since it doesn’t seem like a very big meal. But, alas, that is not necessarily the case. And in this research story, we learn about one plankton hijacking another plankton’s energy, metabolism, and maybe even genetic material – all while victims are still alive. Spooky!

EMBL scientists in the Schwab group have been part of a research project led by Johan Decelle’s group and Laure Guillou, respectively at CNRS in Grenoble and the Roscoff marine station. As more researchers have worked to characterise and understand ocean parasites in the past decade, these scientists focused on better understanding planktonic relationships – specifically, a strain of parasitic Amoebophyra and its microalgal host Scrippsiella acuminata.

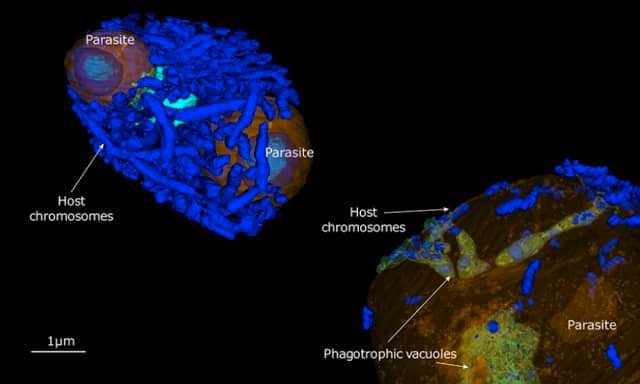

In July, the scientists published findings from their recent research involving 3D electron microscopy combined with transcriptomics. The latter can identify a parasite’s genes and pathways and how they respond to stimuli, including when they are in the midst of overtaking a phytoplankton’s nucleus (Dare we say, ‘BRAINS!’) to hijack energy-producing processes.

Yes, that is what happens to S. acuminata, a single-celled microalgae known as a dinoflagellate, when it’s invaded by the parasite Amoebophyra. S. acuminata isn’t necessarily an innocent bystander in this story either. Many dinoflagellates – including both the parasite and host in this case – are associated with ‘red tides’, harmful algal blooms that cause far-reaching environmental and human health consequences.

Amoebophyra is a parasite but also another kind of dinoflagellate. Much like a virus, one or more will enter the S. acuminata cells while the unsuspecting host continues to swim around in its water world as if nothing has changed, even as Amoebophyra devours its nucleus. Remarkably, S. acuminata continues swimming and photosynthesising as the parasite actively overtakes energy-producing cells in the host’s nucleus.

Next, the parasite begins replicating within this single-celled host, generating more parasites that will eventually depart to find their own hosts and begin this process anew, embarking on their own parasitic conquests. The S. acuminata host, however, eventually dies – a slightly different outcome than something in Zombieland. Undead plankton apparently don’t yet seem to exist.

And while this makes for a good Halloween story – and possibly even your next costume idea – the science does serve a greater purpose.

Stay Always Informed

Join our communities to instantly receive the most important news, reports, and analysis from the aquaculture industry.

“This research is really just the start of shedding light on what’s happening in the wider ecosystem,” Decelle said. “With this type of 3D microscopy, we could observe a process going on inside the nucleus, step by step at nanoscale resolution. Now, it’s a matter of deciphering the mechanisms and seeing where these small activities have implications on a much bigger scale – the environment in which they live.”

Reference (open access)

Decelle, J., Kayal, E., Bigeard, E. et al. Intracellular development and impact of a marine eukaryotic parasite on its zombified microalgal host. ISME J 16, 2348–2359 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-022-01274-z

Editor at the digital magazine AquaHoy. He holds a degree in Aquaculture Biology from the National University of Santa (UNS) and a Master’s degree in Science and Innovation Management from the Polytechnic University of Valencia, with postgraduate diplomas in Business Innovation and Innovation Management. He possesses extensive experience in the aquaculture and fisheries sector, having led the Fisheries Innovation Unit of the National Program for Innovation in Fisheries and Aquaculture (PNIPA). He has served as a senior consultant in technology watch, an innovation project formulator and advisor, and a lecturer at UNS. He is a member of the Peruvian College of Biologists and was recognized by the World Aquaculture Society (WAS) in 2016 for his contribution to aquaculture.